Jul 27, 2021 Books

Steff Green was at a party one night in 2014 when Fifty Shades of Grey came up in conversation. A friend was saying how much she’d enjoyed the erotic, mega-best-selling series, which began life as self-published fan fiction by writer EL James, based on the Twilight series. Green wasn’t a fan. “I was kind of mocking the books a little bit, mocking the terrible writing, and my friend was getting a little annoyed with me,” she recalls. “She was like, ‘It’s not like you could write a book like that.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, yeah, you’re probably right.’ But in my head I was like: Challenge accepted.”

By that point, Green, who made her living as a freelance copywriter and content strategist, had self-published a handful of science fiction novels, which she considered a “super serious” literary project. “I really wanted to be sort of the next China Miéville,” she says. As a lark, she started writing a novella, a romance with paranormal themes. She came up with a pen-name — Steffanie Holmes — and paid a graphic designer $50 to design a cover (direction: “Just make me a cover that looks like a paranormal romance book cover”) then uploaded it to Amazon.

“I thought, you know, in six months’ time I’ll tell my friend about it and we’ll just have a laugh,” Green recalls. Instead, the book sold over 1000 copies in a week, and Green’s writing career had a new direction. (Her science fiction novels, which she toiled over for years, had sold about a hundred.) Green’s list of works today runs to almost 50 titles, including a couple of self-publishing how-tos — she’s an evangelist for the format, which allows authors like her to keep 70% of their books’ proceeds, as opposed to about 8–10% in traditional publishing. She makes a solid six-figure income from writing fiction, and anthologies she contributed to have hit the New York Times and USA Today bestseller lists. Green lives on a lifestyle block near Kaipara with her husband and their cats, and she aims to write 4000 words each weekday. That pace allows her to put out a new novel roughly every two months, keeping her voracious readers happy.

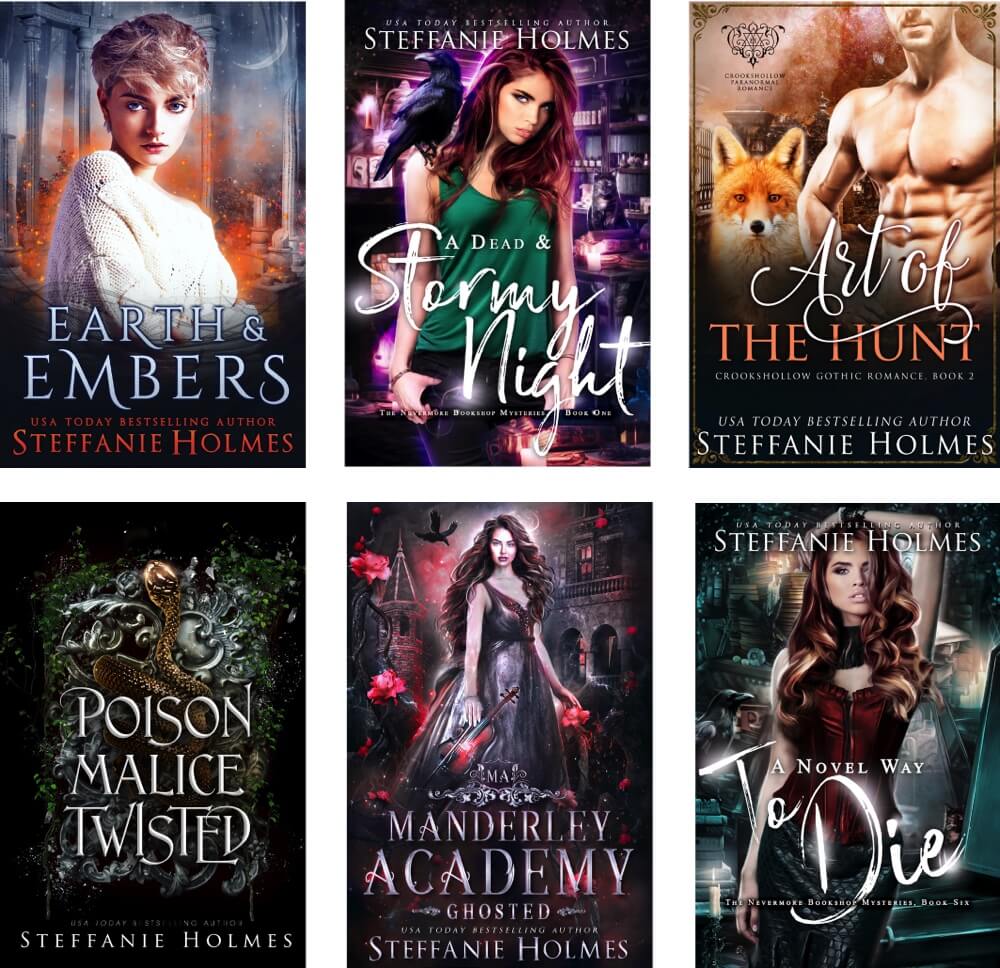

A selection of Green’s novels

Green grew up in Waipawa, a tiny farming town in Central Hawke’s Bay. Her father was a builder, and her mother worked part-time as a nurse and cared for Green and her sister. “Because my dad built our house, it was bigger than other people’s houses, and a lot of people at school called us the ‘rich girls’,” Green recalls. “Which is quite ridiculous — I mean, when I moved to Auckland, I was like, ‘Oh, now I’ve met people who are actually rich rich’.”

Green was born with an eye condition called achromatopsia, which means that her retinas have no cone cells — cones allow us to see colour, see in the daylight and perceive depth. Green sees in black and white, her depth perception is very poor, and her eyes are extremely sensitive to light. She is legally blind, and cannot drive. Her condition is stable and incurable. Green reads enlarged text, and she writes in a darkly lit office on a large monitor with the text colours reversed to white-on-black.

Partly because of her eye condition, growing up, Green never felt accepted by other children. “Kids were mean to me because I was this weird girl with glasses, and I couldn’t play sport — and that was the marker of being a cool person,” she recalls. She found a refuge in the school library, a space where she could draw or read in peace. Books became an escape. She was drawn to horror, suspense and paranormal fiction. She loved VC Andrews, Stephen King, Shirley Jackson, Daphne du Maurier and Dean Koontz. New Zealand author Nalini Singh, who writes paranormal romances, was also an early influence.

Green was “really obsessed with” iconic 90s series like RL Stine’s Goosebumps books, and, later, Sweet Valley High. In high school, she was inspired to write a series of her own, and completed five books. “I’ve always had this sort of commercial bent to my work,” she says, “where I wasn’t just thinking about the logistics of writing, but always imagining myself as a published author and thinking about where my books would sit on the bookshelf.”

Originally, Green planned to be an archaeologist. She studied anthropology and ancient history at the University of Auckland, and pursued internships, field work and volunteer opportunities. She helped with archaeological excavations at a pā site in Bell Block, Taranaki. She met her now-husband on a dig at Queen’s Redoubt in Pōkeno, the fort from which the British launched the invasion of Waikato. Research into Minoan burial practices for her degree took her to Crete. But after graduating in 2006, Green struggled to find a job in the field. “I basically ran into the brick wall of people not wanting to hire me because of my eyesight,” she says. She looked for work for nearly two years. “Again and again, I came up against this thing of, you know, ‘You’re a health and safety risk’, ‘We don’t trust you with artefacts’,” she says. The discrimination was blatant, demoralising — and illegal. “People who had been perfectly happy for me to work for them on a volunteer basis, some of them, when there was a job available, suddenly said no.” Green wishes that the people she encountered as an applicant had looked beyond her disability to her actual skills. “Instead of saying, ‘You’re a health and safety risk’, I wish that people had said, ‘Hey, what are you actually good at?’” she says. “Because there’s a job on every archaeological dig where somebody has to sit in a tent and write down the numbers of all the artefacts that are uncovered, and keep a log of everything that comes out of the ground. I would have loved that job. But no one ever asked me.”

Green considered going back to university for a graduate degree, but she was wary of spending additional years in training only to encounter discrimination again. Instead, she found work translating materials into braille at the Foundation for the Blind. “Which is definitely a place where they can’t tell you that you can’t do a job because of your eyesight,” says Green, wryly. (She learned to sight-read braille to do it.) It was then she started to build a business as a freelance writer, working on her fiction in the evenings or while taking the bus home from work.

She got a break when an editor at a Big Five publishing house in the United States responded to her query, and she started sending the editor work. Over the next few years, Green wrote three novels that were rejected, before the editor accepted a fourth. But then the editor retired, and her yet-to-be-released book was cut.

After her frustrating near-miss with traditional publishing, Green felt compelled to get her books into the world. Print-on-demand technology and the rise of ebooks (largely driven by the popularity of the Kindle) were transforming self-publishing, which had long been stigmatised by publishers and critics as a domain only for vain amateurs and paranoid cranks. Green decided to self-publish all four of her science fiction novels. “I loved the whole process so much,” she recalls. “Actually holding my book in my hands — finally, after all this time! — and choosing the cover, and figuring out how to write a blurb, and getting it up on Amazon… All this stuff, I loved it.”

Her latest book, Poison Malice Twisted, was released in May. Her next one won’t be far away. “Right now I have more books in my head than I have time to write,” says Green. She has a very different life than the archaeology career she originally dreamed of, and it is one that she has made herself. “I’m really proud, and I feel okay with being proud of what I’ve been able to pull out of thin air,” she says. “My dad ran his own business as a builder, so I’ve al- ways seen someone be their own boss. And I think that was always who I was going to be. I just didn’t know it.”

—

This story was published in Metro 431 – Available here in print and pdf.