Dec 3, 2014 Books

Dylan Horrocks

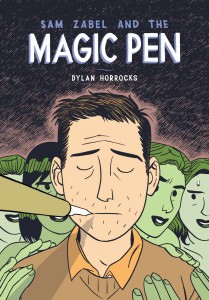

Dylan HorrocksSam Zabel and the Magic Pen

Fantagraphics, $29.99.

Dylan Horrocks hasn’t released an extended work since 1998’s Hicksville. In 2002, he won an Eisner Award, which non-comics publications like to call the “Oscar of comics”.

This comparison ignores the disparities through which non-mainstream, magic-realist cartoonists like Horrocks can win major awards, but the point remains: he’s significant, and it’s exciting when he announces a new work, especially if it’s his first graphic novel in 16 years and it’s a sequel, as autobio kind of necessitates.

Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen isn’t explicitly autobiographical, but the sweater-clad protagonist, Sam Zabel, does seem familiar. He’s an artist struggling with writer’s block, toiling away writing fascistic, misogynistic superheroes — although Sam makes the distinction that superheroes aren’t inherently bad, he’s just terrible at writing them.

The narrative kicks off when Sam visits Christchurch and stumbles across a (non-existent) New Zealand comic from the 1950s, The King of Mars, which the reader can enter through magic. From here on our hero, sardonically speaking, journeys across swathes of fictions, attempting to unravel his complex relationship with fantasy and creative culpability. Heady stuff.

Comics about comics aren’t groundbreaking, especially with autobio elements thrown in, but Horrocks knows this, openly referencing the Alan Moores and Grant Morrisons who precede him. The strength of this book is the alacrity with which it embraces modernity. A reflexive eye is cast over comics history, from 13th century manuscripts to erotic Dojinshi manga, but the overarching style is fashionably up-to-date.

The Magic Pen bristles in full colour, a rarity within the tortured artist sub-genre, which has traditionally harnessed expressionistic black and white. The vivid hues are most striking in the genre plays populating Sam’s fantasies: the reds of Mars, the ambers of Lou Goldman’s Lady Night. In some of these parodies, colouring is used in lieu of a closer eye for formal convention, but as shorthand it’s effective, and the art is self-assured.

The book was originally serialised online, and is strictly linear, with none of the epistolary quirks that characterised Hicksville. This suits the ideological focus of The Magic Pen, in which there are roundtable philosophical discussions. However, complexity is lost in characters other than Sam. These ancillary figures, his wife and traveling companions, inhabit female roles built in reality rather than escapist fiction, and I would have liked to spend more time with them, and away from Sam. An extensive section in which this does happen, when we follow manga-pastiche Miki to her homeland, is a highlight, creepy and deeply affecting, because for once the dramatic stakes have been extended.

The first chapter of the book is called “Anhedonia”, and I’d be hard pressed to believe it isn’t a reference to the working title of Annie Hall, another disjointed treatise on female representation. Such intertextuality permeates The Magic Pen; nonetheless it can be enjoyed without annotation. The book’s strength is its modernness, and Dylan Horrocks isn’t playing at youth. He knows his stuff, and assumes you do too.