Dec 19, 2019 Books

A righteous poet policeman has to juggle the interests of justice with those of the Communist Party.

Despite being a genial fellow, Chief Inspector Chen Cao is not universally liked at the Shanghai Police Bureau, principally for the following reasons: he’s regarded as a baby detective, yet because of the Communist Party’s regard for formal education he has leapfrogged more-experienced colleagues; he has an apartment all to himself in a city experiencing an acute housing crisis; he’s a published poet, and has translated the poems of

T. S. Eliot and other Western versifiers, as well as whodunnits, into Chinese.

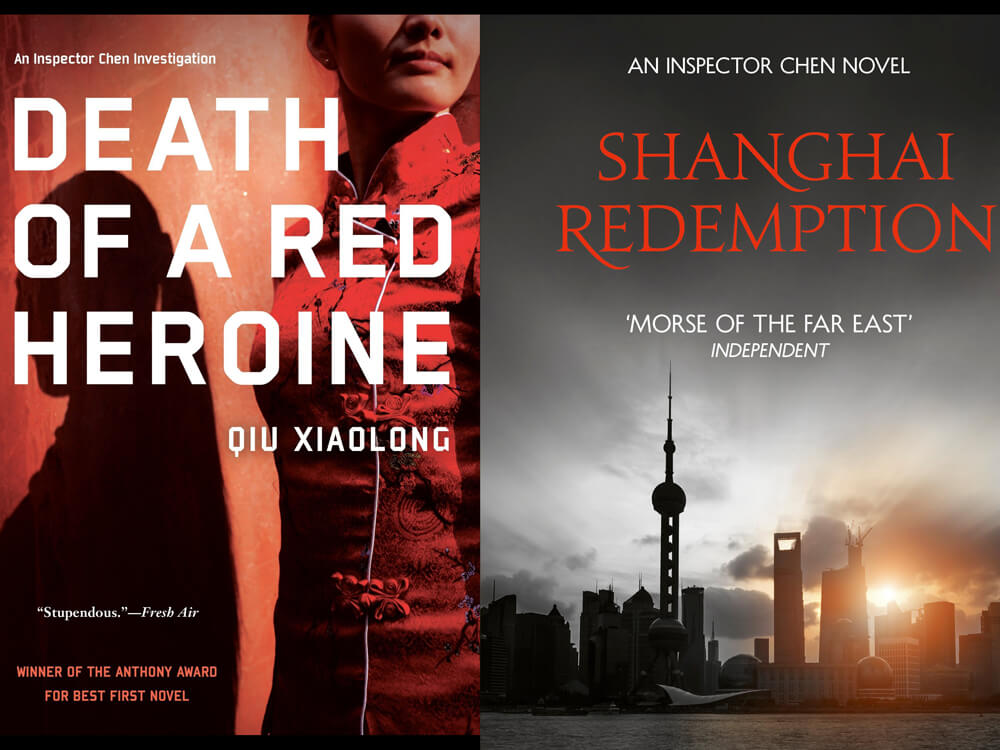

For some of his colleagues, Chen’s lyricism is possibly his most irritating trait. In Death of a Red Heroine (2000), author Qiu Xiaolong’s first outing for the inspector, the naked body of a young woman—a celebrity Communist Party member—is found in a canal. Strangled. Confronting the horror, Chen summons lines from the Tang dynasty (618-907) poet Li Shangyin:The zither, for no reason, has half of its strings broken,

One string, one peg, evoking the memory of the youthful years.

However, Chen’s abiding soulfulness and recitation of various couplets sometimes does the trick. When asking a journalist out for lunch, and to take his mind off the zither, he enlists Li once more: When, when can we snuff the candle by the western window again,

And talk about the moment of Mount Ba in the rain?

Chen is something of a foodie, and soon the couple are wolfing down such treats as are to be found in the back streets of Shanghai: pork stomach on a bed of green napa (a type of cabbage originating in the Beijing region); smoked carp spread on fragile leaves of jicai (a wild herb known as shepherd’s purse). Soon the couple are also practising tuishou, an intimate push-hand sparring exercise, which unsurprisingly leads nowhere: Chen is that trope of detective novels—a loner truth-seeker, with a backlist of stunners who got away.

To date, Chen has featured in 11 of Qiu’s softly boiled police procedurals, most of which are set in the 1990s. They are vivid depictions of life in Communist China, mostly in the racy financial city of Shanghai, on the estuary of the Yangtze where foreign companies and factories, as well as local entrepreneurs, are appearing “like bamboo shoots after a spring rain”.

Qiu gives a fine and textured guide of a city and country in flux, transitioning between socialist politics and capitalist economics. It’s at least 15 years since the terror and waste of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution ended. Nevertheless, Chen’s superior Commissar Zhang gees him along with choice quotes from the revolution’s instigator, Mao Zedong: “We mustn’t be afraid of hardship or death.” Zhang is one of Chen’s detractors who doesn’t get the T.S. Eliot malarkey—an indicator of “ideological ambiguity”, he thinks; when Chen suggests the victim in Death of a Red Heroine may have suffered “traumatic” episodes in her early years, Zhang replies: “Another of your Western modernist terms?”

The unreconstructed Zhang aside, the saying “xiang qian kan” (or “look to the money”) is now often heard in Shanghai. Outbreaks of Western decadence and all round loucheness are on the rise. Case in point: In Death of a Red Heroine the victim has tasted caviar, owns bling and a fair few lipsticks, and takes holidays not once but twice a year.

Qiu also takes readers on a tour of the corridors of power, where corruption is ubiquitous, bureaucrats sleazy, and the protected children of influential party members —dubbed HCCs, or High Cadre Children — murderous. The author is himself a poet and translator of Modernist poetry. In the wake of the bloody anti-democracy crackdown in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, he permanently decamped to the United States, and began channelling unease through his protagonist.

Chen is a righteous man operating in a world of subterfuge. He’s a party member, who can brown-nose and strategise with the best of them. His work is a juggling act. As a cop he must seek justice by punishing the perp whoever he or she is; as a party member he must serve, above all, the often-conflicting interests of the party. In Shanghai Redemption (2015), Chen is brought low by years of compromises, and ultimately concludes “the system has no place for a cop who puts justice above the interest of the party”. A poem by the brilliant female Song dynasty (960-1279) poet Zhu Shuzhen probably consoled:

At the Lantern Festival this year,

The lanterns and the moon are the same as before,

But where is the man I met last year?

My spring sleeves are soaked with tears.

Death of a Red Heroine (2000), Soho Press, and Shanghai Redemption (2015), Minotaur Books, by Qiu Xiaolong; available at Auckland Libraries.

This piece originally appeared in the November-December 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline ‘Let’s go… Shanghai’.