Mar 7, 2023 Arts

In the dead of winter between lockdowns, I put three pebbles in my pocket and went on a writer’s pilgrimage to New York. I’d just turned 80 and thought it was time that I pay homage to the three writers who had made the greatest impact on me.

I had a pebble from Karekare to put on the grave of Herman Melville in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. As a young lifeguard I’d slept in a brass bed on Karekare beach in a makeshift whare and read Moby Dick into the night. The second pebble — from Whatipu, at the head of the Manukau Bar where I’d once swum the treacherous harbour mouth — was for the great poet Walt Whitman. He designed his own tomb in an overgrown graveyard in Camden, New Jersey, and I wanted to sit by the door and have a conversation. The last pebble I’d picked up from Rocky Bay on Waiheke Island. I would place it on a brass memorial plaque in New York’s Library Way on 41st St, between Park and Fifth Avenue, for the Chinese poet Gu Cheng. There in Manhattan, I removed my shoes and stood before the plaque of this lost soul who’d fled to New Zealand to find a haven on Waiheke but found only despair in the bleakness of exile.

I first read Gu Cheng decades ago when the Chinese consulate-general suggested that I, as mayor of Waitākere, should visit China and select a sister city to establish a relationship with. I was apprehensive but charged with excitement. I was born in a Year of the Dragon and had flirted with Communism in my teens. During Socialist Unity Party meetings in Upper Queen St, I felt at ease with people who had been trading with China, had walked with Chairman Mao on the Long March, and had gotten to know Rewi Alley who had done so much to establish a New Zealand presence. By some fate I had also been present when Norman Kirk opened the Chinese embassy in Wellington in 1973. So I felt that I had a relationship with China, and I believed I understood the struggles that China had endured to move into the 20th century as an economic powerhouse. The fact is I knew very little.

The city that was chosen as Waitākere’s sibling was Ningbo, a major powerhouse on three rivers. Within days of arriving I was on a bike joining the thousands of people who crowded the roads, the alleyways and the river paths. I felt at home, comfortable and safe. I felt I had lived another life in China. It fitted me like an old suit.

The Chinese officials had given me a young assistant to translate and watch over me. It wasn’t long before I realised that every move I made was being reported on. The rooms reserved for foreigners at the hotel were bugged for conversations. This was the way that China had operated for some time. It needed to know your thoughts and actions. My ‘helper’ turned out to be a scholar who knew a lot about Chinese art, music and poetry and he gave me a copy of the works of Gu Cheng, who he said was living on Waiheke Island in Auckland. He asked if I had met him. No, I said, but my father lived on Waiheke, and on my return I would make contact.

From the start, I was totally captured by the poetry:

The dark night gave me dark eyes,

But I use them to seek the light.

This two-line poem from 1979 gave Gu Cheng instant success and quickly became iconic to young Chinese readers. Called ‘One Generation’, it has been intensely studied. The poem acknowledges the darkness of the Cultural Revolution — the horrific damage it did — as the poet seeks not to hide away but to guide the reader from the darkness to the light. I became obsessed with the poet who had written these lines and why this genius had chosen to come to New Zealand to live in relative isolation and solitude with his wife on a small unsealed road in Rocky Bay.

Gu Cheng was born in Beijing in September 1956 — an important year in the Chinese calendar and in China’s modern history. A level of post-revolution prosperity was slowly emerging and Chairman Mao had decreed that this year be one of celebration and peace. It would not last. Gu Cheng’s father was a highly respected poet and soldier in the People’s Liberation Army. His mother was a script reader. As a young boy, Gu Cheng is said to have created his own birdlike language that only his sister could understand and translate into Mandarin. At six, he wrote his first poem and by eight he had shown an enormous talent for conveying visual images in poetic language. When Gu Cheng was 12, his family was swept up in the Cultural Revolution and its resulting horror. Mao decreed that the new China would need the people to rise up and destroy the ‘four olds’: old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits.

Middle schools were closed, as were colleges and universities. It’s estimated that, over the following decade, between 400,000 and three million people were killed. The teaching of Confucius disappeared; monasteries, temples and historic buildings were destroyed. Mao’s Red Guards began moving through villages, seeking those who needed to be re-educated. In 1968, Gu Cheng’s family was visited by Red Guards with a waiting truck and taken to the country, into a landscape of deep poverty. Within a day they had moved from relative safety to uncertainty and anguish, working in the fields by day and sleeping on brick beds at night.

Being sent to the countryside meant that the young poet and his father were forced to dig rice pits and raise pigs. Inspired by nature, Gu Cheng found solace in writing and he was prolific. He became part of a new earth, a new sky, new sounds. Fascinated by insects, he found a quietness in observing crickets and locusts in the fields and waterways that teemed with wildlife. He appears not to have been troubled by hard work and poverty, although the days spent barefoot carrying water up steep hillsides must have been beyond pain. What mattered was that he could lift his heart with his words. The manual work faded when faced with poetic imagery, such as these visions in ‘Poverty Has a Chilly Nose’:

Wheat fields in every direction

Are gold reflections of the sun

Dust storms rise in solar winds

The grasses clump

So hot so hot

Mao died in September 1976 and the Cultural Revolution came to a slow and grinding halt. The Gu family returned to Beijing as a unit beaten but not broken, Gu Cheng said, and he continued his education. A different China emerged. Underground magazines started and Gu Cheng quickly joined other poets who were wanting to share writing. Their work was described as menglong shi — obscure or hazy poetry — and collectively the young group came to be known as the Misty Poets. They mixed dark themes with uplifting, romantic and deeply felt language that lifted the spirits and attempted to banish the last decade of pain and bloodshed. It was an exhilarating moment for Chinese literature.

The Misty Poets had an astonishingly swift arrival. While some literary groups emerged over a long period, the Misty Poets had instant success with young Chinese readers. China had had a long history of particular poetic works making a mark on culture, and after a decade in which cultural riches were stripped and forbidden, the appearance and reappearance of artworks in theatres, on streets and in forums was cause for enormous celebration. People would leap on tables in bars and restaurants and hold an audience enthralled with words of romance, beauty and joy. An absolute zest for life and living was emerging; a reawakening of subdued and repressed energy.

In April 1976, in the last months of Mao’s life, millions of people had gathered in Tiananmen Square to protest the power of Mao’s allies the Gang of Four, the treatment of the recently deceased premier Zhou Enlai, and the way China was treating its history and traditions. Poets and writers were at the forefront as mourners laid wreaths and tributes to Zhou Enlai in the square. Then the regime cracked down on the gathering: Gu Cheng himself witnessed the ruthless beating and killing of protesters. This latest China was revealing itself as brutal as the past incarnations.

In these tumultuous times, Gu Cheng was a rising star. He had no problem getting published, and in 1979 he was already becoming a named poet when a small newspaper carried his major work ‘Nameless Flowers’. It sold tens of thousands of copies. An icon was born. Gu Cheng also harnessed the psychological energy that emerging China felt was so important to become a global power. Internationally, he was compared to Walt Whitman and already he was getting invites to tour the world’s universities and take the podium to read his work. As he refused to learn English, he did so with the help of translators.

By 1983, Gu Cheng had published more than 300 poems. He was the Dylan of China — hot property, and often mobbed by adoring fans. He had found fame and the Misty Poets had come from obscurity to be a sensation. In August that year, Gu Cheng married his wife, Xie Ye, whom he had met on a train. The couple appeared to be a perfect unit. They were both writers and both had a deep love of the freedom of the countryside, rivers, lakes and the romance of nature.

The marriage started well but along the way the intensity of Gu Cheng’s work, his rising fame and the ideological battles of the time seem to have taken a toll on his life and his behaviour. He talks of something happening to him that fills him with horror. He becomes depressed and troubled, and, although he doesn’t show it, he is starting to hear sounds and voices in his mind.

In May 1987, Gu Cheng left China to read his poems in Germany. It was an enormous success. The German appearances were sold out, and he felt this was the beginning of an international career as a poet and a teacher. It also meant that he would not return to China. He had been in correspondence with a group of young Chinese students at the University of Auckland and they had lobbied for him to come to Auckland and take up a residency. He accepted, and in 1988 the poet and his wife came to Auckland and bought a small house on Waiheke island. It was a place of refuge — a hiding place like that described in his 1980 poem ‘Martyrdom’:

My friends may come searching,

But will not find me. I’ll be well hid.

At these things in the suburbs

Towering like building blocks

I feel secret surprise.

I talked to people who knew the poet in those first years on Waiheke. There are periods of Gu Cheng and Xie Ye being very involved with the community. She makes spring rolls and sells them at the Saturday Ostend Market. He walks the Rocky Bay roads in the early evening and often into the night. But some saw a moody and often sombre figure. He had a habit of wearing on his head a cut-off trouser leg; he said this was to keep out distracting sounds, words that were confusing him. He was losing concentration for what he needed to do and know. Rocky Bay resident Julie Myer got to know them well and thought them the most adoring couple. They had by now a young son, Samuel, who started at the local school. Myer told me that Xie Ye and Gu Cheng would sometimes go a week without speaking — Xie Ye put this isolation down to Gu Cheng’s intensity and his unwillingness to see the real world around him. Others felt that Waiheke, with its close community, frightened him and the dream of paradise on a subtropical island was losing its magic.

Gu Cheng’s paradise had been enhanced — or complicated further — by the arrival of the young woman he had been involved with in China, Li Ying. Her move to Waiheke had the support of Xie Ye, but the trio’s paradisal kingdom “inevitably became riven with jealousies”, as scholar of Chinese literature Hilary Chung put it. Auckland city councillor Mike Lee remembers Xie Ye, Gu Cheng and Li Ying as extraordinary people. He would often see the three of them, closely connected, walking around the main centres of Waiheke — and always at the Saturday market, that melting pot of island life.

Gu Cheng also felt deeply that China was going down the wrong path — that all the work, effort, pain and suffering had come to nothing. Although China was becoming stable, there was a sense of deep and troubling behaviour by officials. Through the 1980s, the divides between intellectuals and young people who argued for political and economic reform and the older revolutionaries who believed literature and art should serve state goals grew sharper. Chinese writers had a history of making a statement of their deepest beliefs by taking their own lives, most famously Lao She, who had risen at dawn one day in 1966, filled his pockets with stones and walked into the Lake of Great Peace.

Gu Sheng recorded his own view of death in the 1988 poem ‘Grave Bed’:

I know death approaches it’s not tragic

My hopes are at peace in a forest of pines

Overlooking the ocean from a distance like a pond

Afternoon sunlight keeping me mottled company

A man’s time is up and man’s world goes on

I must rest in the middle

Passerby say the branches droop

Passerby say the branches are growing

If Gu Cheng was becoming more disheartened in life, he was temporarily cheered by an invitation to return to Germany for another reading and educational tour. Xie Ye and Gu Cheng decided to leave Waiheke for Germany for 18 months, while Li Ying remained behind. Gu Cheng seems to have taken his trouble with him, however. Visiting the University of London in 1992, he told the audience: “Another sound came to me… This was a dangerous sound. I don’t know where it came from. But it sounded endlessly inside me, saying ‘deedleedee’. Then the trees started dancing in the sky. The earth was covered in a white light. Bats seemed to come flying out of nowhere. The night had turned into a window that was broken. I really felt I was crazy. Trees were dancing in the sky. Everything was speaking, the poet saying ‘poet, poet, poet’, the world saying ‘world world world’, China saying ‘China China China…’ The last thing I heard was a dish saying ‘dish dish dish’.”

Then Gu Cheng learned that, back on Waiheke, Li Ying had left the ménage of the poet and his wife and eloped with a martial arts instructor. His downward spiral worsened. The poems and a memoir he wrote in Germany at this time are full of ghosts, worries about “slipping and falling”, and the “disappearance” of Li Ying. Then, too, Xie Ye had fallen into a new relationship in Germany, news of which caused Gu Cheng to spiral further.

The couple returned from Germany to Waiheke in the spring of 1993. Mike Lee remembers talk that Gu Cheng had become deeply troubled and seemed to have lost his energy. It was thought that Xie Ye’s lover was coming from Germany to join them. Lee recalls being on the wharf waiting for the ferry and seeing Gu Cheng and Xie Ye awaiting the arrival of someone, assumed to be her lover. Gu Cheng seemed deeply depressed, dark and moody. He acknowledged no one on the wharf. Xie Ye was wearing makeup — which was rare — and a beautiful dress. It would be the last day of her life.

The following day, on the six o’clock news, the entire country heard that the Chinese poet Gu Cheng had killed his wife with an axe and had taken his own life by hanging. The island community was traumatised. Many found the tragedy unbelievable, and in China, Gu Cheng’s death was greeted with almost national mourning. The greatest Misty Poet had died in violent and horrific circumstances and committed a great wrong as his final act.

The couple’s son, Samuel, was in the care of a local woman at the time. He continues to live on Waiheke and is well liked.

The story of Xie Le and Gu Cheng has always stuck with me — as Gu Cheng wrote, “people who have died make the air tremble”. I have read and reread the poet’s work over the decades, trying to come to terms with the murder and suicide. I tread a fine line between admiring Gu Cheng’s work and genius and deploring his descent into misogynistic madness. As I stood at Gu Cheng’s memorial in New York, thinking of these contradictions, I read his words and placed a pebble to his memory.

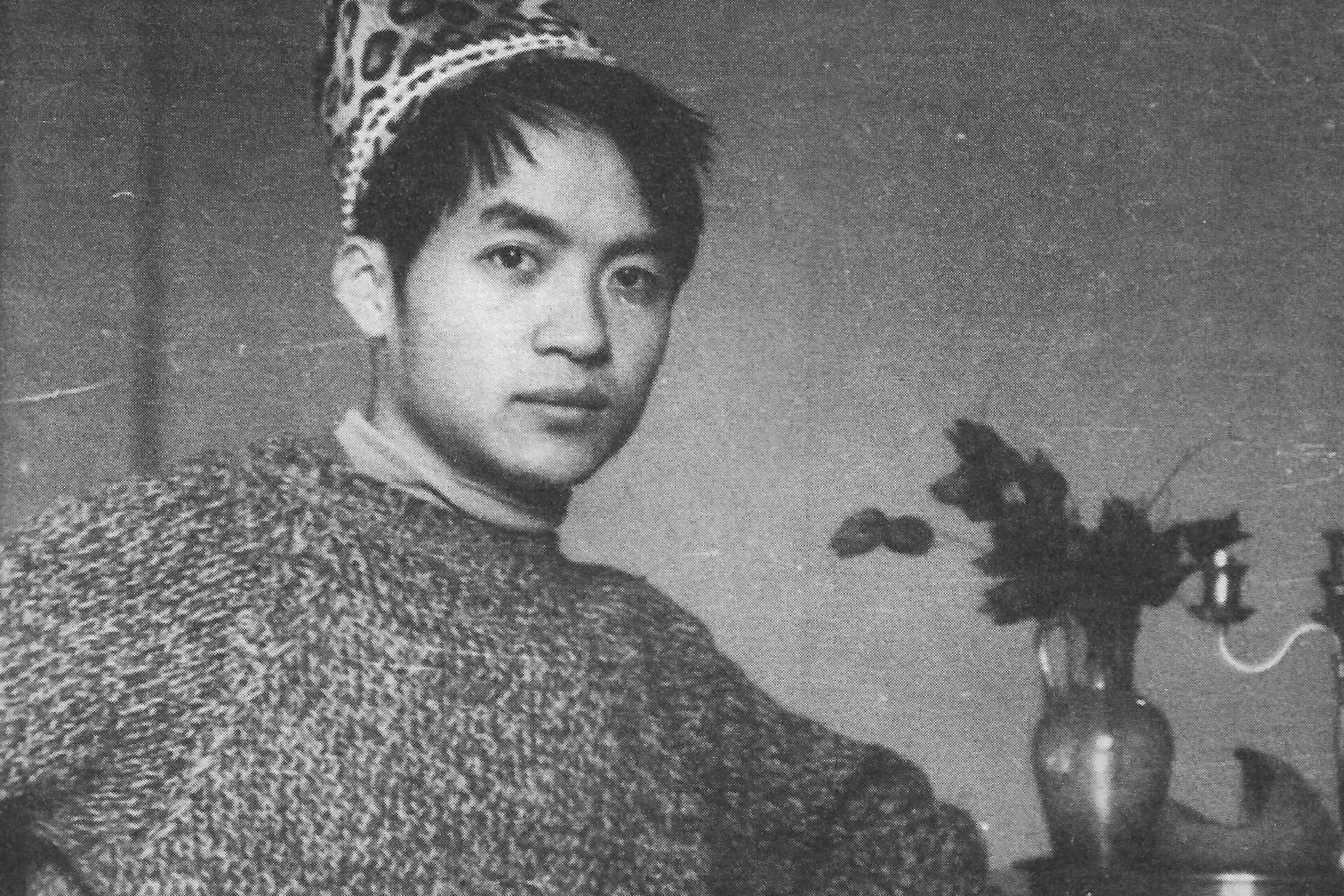

Photograph from Nameless Flowers: Selected Poems of Gu Cheng, George Braziller Inc, New York, 2005

–