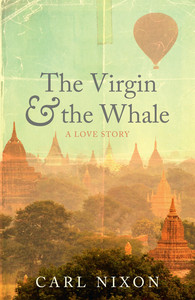

Sep 2, 2014 Books

At the close of The Virgin and the Whale, readers could feel they have been in the company of some very fine human beings. There is a strong moral heart to the book. Characters are

At the close of The Virgin and the Whale, readers could feel they have been in the company of some very fine human beings. There is a strong moral heart to the book. Characters aredecent and well behaved and if they ever do wrong, it is because they have no choice. Central are nurse Elizabeth Whitman and her patient Paul Blackwell, who prefers to go by the name of Lucky.

There are Elizabeth’s family, her son and parents; and Lucky’s luckless wife, whose husband has returned from the trenches of the Great War with no recollection of his previous life.

There is also, never far from the foreground, the genial author himself, who introduces the novel with a story of its provenance.

The novel takes as its inspiration a tale purportedly told to Nixon by an elderly man, whose identity he protects by only ever using the initials MN and setting the novel in a city he calls Mansfield, but is more a loving portrait of Christchurch as it was in the first decades of the 20th century. MN’s story is about his mother, and how she fell deeply in love with a man who had no memory.

Language employed is plain and doesn’t shy from cliché. A cook has a doughy face and eyes like raisins. A tiger is seen “vanishing into thin air like a ghost”. Where such language might otherwise annoy and disappoint, in this novel it mostly assists the reader re-enter the period and the storytelling styles of the time.

The authorial voice continues strongly throughout the novel, sometimes obtrusively, as if Nixon is keen to drum home the notion that we are formed by our stories, that our memory not only makes us who we are but also defines who we are capable of loving, or not.

Mrs Blackwell mourns a husband who is lost to her while Elizabeth, having no knowledge of the man he was before, falls in love with the man he is now. There are frequent asides about the war itself, the forms of battle and types of guns, as well as information on the nature of Lucky’s headwound with reference to the famous 19th-century case of Phineas Gage.

There are many musings on the nature of storytelling, the nuts and bolts of how we go about it. In postmodern style, the author often addresses the reader directly. “At this point the story will be frustrating certain readers… Perhaps you have already drawn back the book, set to lob it towards the far wall.”

This is dangerous and brave, and could so easily fall flat. It is through Nixon’s skill as a storyteller that it doesn’t — the unfolding love story and jeopardy posed by Lucky’s wife and local psychiatrist keep us reading.

Further risks are taken with the inclusion of an ongoing children’s story that Elizabeth tells her son as comfort for the loss of his father, who is missing in action. In this otherwise excellent novel, these are the weakest sections.

It is too tempting to race ahead and return to the company of Elizabeth Whitman, who really is a damn fine woman. Honest, loving, clever and sensible, she comes to us complete with the idioms and mores of a vanishing era of Pakeha history.

Published in Metro, June 2014.