Sep 15, 2016 Books

Hera Lindsay Bird’s debut is nihilistic, offensive and sexy. Not your standard book of New Zealand poetry, then.

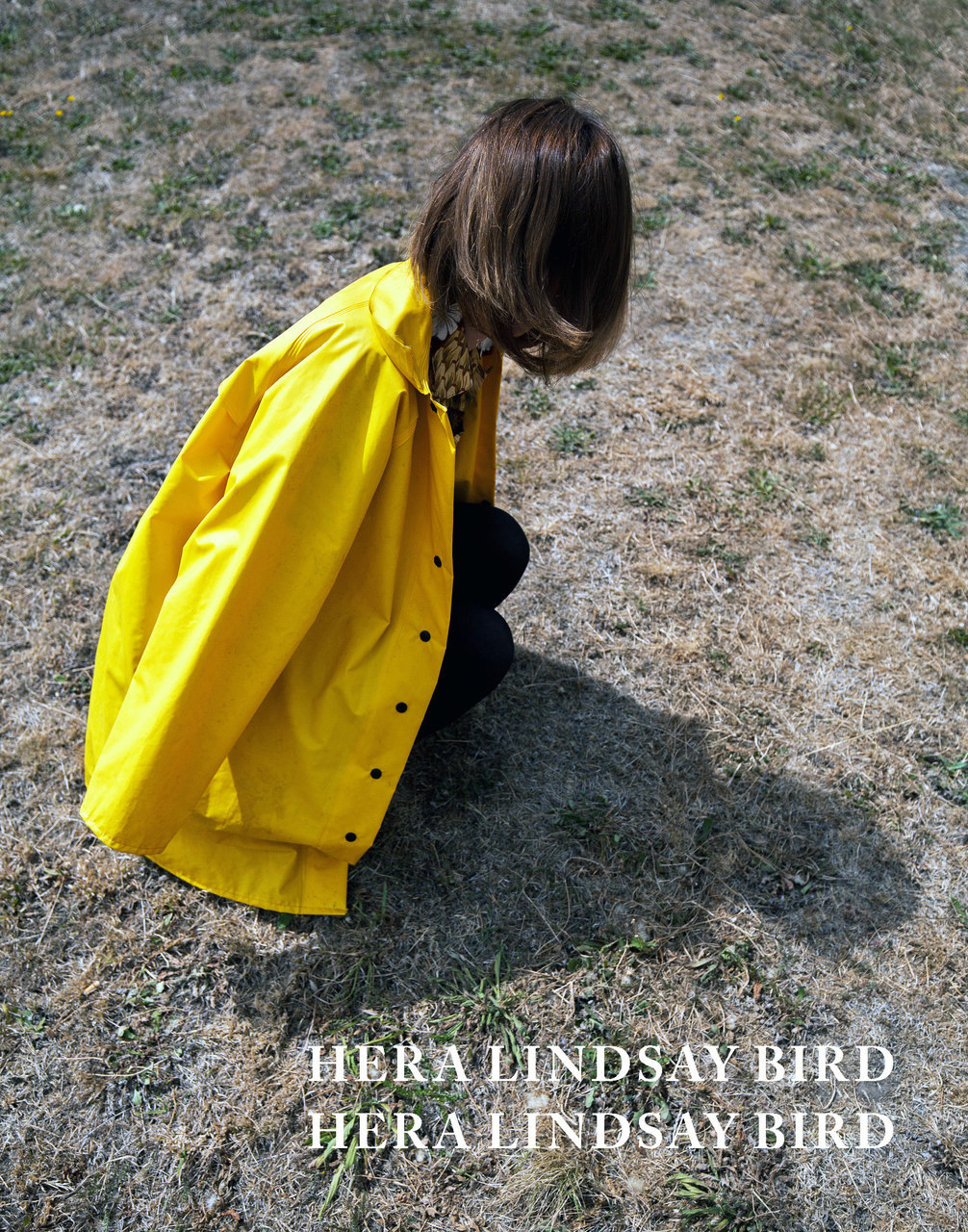

Photo by Rachel Brandon.

Hera Lindsay Bird

Hera Lindsay Bird

(VUP, $25)

Every so often — I can’t remember the last time — someone comes along and enters the well-kept, nicely decorated house of New Zealand poetry without knocking. Then this person starts smashing the furniture and writing rude words on the walls. “You can’t do that!” you say. “That’s Laura Ashley wallpaper!” Then this person — let’s call her Hera Lindsay Bird — says, “Let me explain!” And sets the house on fire.

Nobody likes their house being set on fire, the co-ordinated pastels and vacuous art and the new ensuite going up in flames, but it’s pretty exciting. The primary impulse in this new, terrific book of poems is a delight in destruction. It’s nihilistic and offensive and sexy, but, as John Newton says astutely on the back cover, “The wickedest problem in Hera Lindsay Bird is not sex but taste.”

There are so many things we simply don’t say, and the reason we don’t say them is that they are not tasteful, they are not nice, they are offensive. And I don’t mean in a “politically incorrect” way. I mean in an in-your-face, fuck-you kind of way. That’s Hera Lindsay Bird’s way. She just doesn’t care, and reading these poems makes you realise how much caring what other people think gets in the way of good writing. So much contemporary poetry seems designed to show you how sensitive and good the poet is. How perceptive. A bit of observation, a bit of perception, packaged up in a neat anecdote with O! an epiphany in the last line that has the poet quivering like some sort of ecstatic jelly. The poem itself is an ecstatic jelly, quivering in its jar on a shelf with all the other ecstatic jellies of New Zealand poetry.

All the gleeful smearing of shit everywhere doesn’t conceal the fact that here is a very fine poet at work.

You can stand only so much jelly, and it feels good, reading these poems amidst the sticky mess and the broken glass. The titles give you some idea: Hate; The Dad joke is over; Everything is wrong; Keats is dead, so fuck me from behind. Need I go on? I’ll go on.

Nobody writes like this in New Zealand. You’d have to look far away — to America and Patricia Lockwood, say, or Michael Robbins, maybe Frederick Seidel — to find poets who recognise that good taste is what keeps the old capitalist machine ticking along, and that the whole thing needs some gasoline and a match. Still, I feel for Keats. A little respect! But no.

There’s more, though. All the gleeful smearing of shit everywhere doesn’t conceal the fact that here is a very fine poet at work, with a wonderful gift for metaphor and simile, effortlessly inventive and bang-on. These lines, for example, from Love comes back:

Love like Windows 95

The greatest, most user-friendly Windows of them all

Those four little panes of light

Like the stained glass of an ancient church

vibrating in the sunlit rubble

of the twentieth century

How can you not love that? Isn’t that fantastic? She also has a go at American poet Mary Oliver, which earns her more points in my book. Oliver is a nature poet, much beloved, who seems to spend her days wandering though meadows in New England, trailing her fingers through the wildflowers, and having spiritual experiences. Well, that’s okay, I suppose, if you own meadows. “You do not have to be good” is the opening line of her best and most famous poem. Hera Lindsay Bird’s poem is better, hopeful but not reductive, acknowledging difficulty, complexity, plurality:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to be anything.

This is not an anthem for the world.

This life is a hard life and

It crushes people

But it’s also weird and full of heat

Crocodiles asleep in their red tent of hunger.

This book bugged the hell out of me — there are poems here that don’t work, and go on way too long, such as Monica, which, like Friends, the long-running sitcom it’s about, needs its own canned laughter to carry it. But these poems take risks, so of course some fall over. And the successes are many, and astounding.