May 14, 2016 Books

Be it said that I am an acknowledged Writers Festival groupie. But I am also, and forgive me for romanticising my flaws like this, a hard bastard when it comes to good session design. I react to bad chairing and writers who can’t deal with public speaking but agree to do it anyway and ill considered panel construction and basic bad crowd control by frothing and venting and asking for heads on plates. None of these things have been issues so far. I am writing in the altered and highly weird state of mind that comes from absorbing high quality information for an overstimulating hour and then doing it again while the first hour is still digesting and then doing it again and again and then not stopping: a whole damn day of it and it was almost all excellent. My head is not spinning so much as attempting to explode and implode simultaneously. The forces are balanced but the pressure is considerable.

Enough generalities. Carmen Aguirre. Please marry me. I had intended to start this day with Herman Koch’s session in the huge ASB Theatre, but I was in that same theatre last night for the festival curtain-raiser, along with every other human being it would hold, and I saw Aguirre in storyteller mode. Her story happened to concern her past as a trained Shakespearian actor, which handily explained her ability to comand a stage while also serving to demonstrate it. She has phenomenal presence. So I went to hear her instead of Koch. (Two, three, or sometimes four sessions on simulateously throughout these three days, and some of the choices are not easy.) I was prepared to be impressed, but actually, I had no clue what I was in for.

Aguirre’s two published books are memoirs, so anything I say about her life in a sense constitutes a spoiler. Not that I know for a fact the books are worth reading; I’ve met writers with astonishing life stories and the raconteur’s gift and no particular ability to write before now at festivals. But Aguirre read from both her books and both passages struck me as good enough that I now own the first book and am eyeing the second. Anyway. To appreciate some of what made this session such a knock-out experience, you just need to know that on the first day of Aguirre’s first professional acting course, her teachers, who were very switched on to subtleties of body language, took her aside, and said, look, you are not going to get through this course without therapy. You have PTSD and it’s blocking you. “I couldn’t tell them that I’d been with the Chilean resistance 18 months earlier, because obviously I’d sworn an oath never to tell anyone; which makes the books I’ve written on the subject a little ironic… But someone has to write this shit down. There’s a lot written about revolutions that triumph. We did not triumph, we lost, colossally.”

Aguirre’s self-possession and formidable intelligence are hard to convey. But this was a thrilling and mind-expanding hour. A remark worth pondering on the general subject of confessional writing: “I’m a very firm believer that if you’re writing for personal catharsis, you’re wanking. I write for universal experience”. Her comments on the USA’s current practice of quietly funnelling funds to the extreme right in Central and South America, “so that ‘legitimate elections’ can be seen to go the way the US would prefer”, were a useful thing to have in the back of my head during the day’s evening panel discussion of the current state of America. I wished she had been in the room to raise them.

You would have to say, looking at the current numbers and taking my six sessions today as representative evidence, that this is a festival on top of its game.

The Aguirre session was I think sold out; it was certainly packed to the gunnels. So was the opening night, and at least three more of the six sessions I was at today. This on a working Friday. This is insane. I think the festival may have passed some sort of success-breeds-success tipping point in terms of getting onto the yes-we-must-certainly-always-do-THAT annual events list of significantly more people than ever before: I would guess as a result of

1) Going annual, and

2) Consistently delivering the goods. You would have to say, looking at the current numbers and taking my six sessions today as representative evidence, that this is a festival on top of its game. It does occur to me to wonder where they’re going to put the audiences if they grow any more. An opera professional I know slightly once complained to me that Dames Kiri Te Kanawa and Cath Tizzard screwed Auckland over when they contrived to get the Aotea Centre built. “It isn’t a music venue, it’s too damn big. The thing’s a conference centre”. And thank goodness; at least from a writers festival perspective. But we may be on the verge of needing a conference center with a second conference center out the back.

Second session: Jane Smiley. Would marry her also. Less of an astonishment than Carmen Aguirre, but only in that I’ve been reading her for years and I’ve heard her speak before. She has one of contemporary literature’s sharpest and most insatiably curious minds. (The Kim Hill of novelists.) Picture her picking up her own book, flipping through it, tossing it aside like trash. “Mmm… nah.” And then explicating her little mime: “This is what I love about the novel. As a reader you’re an agent in your own world. Jane Smiley is this big famous writer, what do you care? You don’t like her book, you toss it. The more you feel like an agent, the less likely you are to do what people tell you to do. Novels teach people to think”.

Her latest project, just concluded, is the 100 Years trilogy: three books, tracking an agricultural family’s history in America, one chapter per year, over a century. Agriculture because “US Agriculture is so very much stranger than you think it is”. In token of which she was wearing a sweater she had knitted herself – very natty, I took it for upscale designer gear – made from soy beans. “Because obviously you’d think to make yarn from soy beans”. She wrote the books in an accelerating rhythm: for each volume, she began with two weeks of writing 750 words a day, and then moved to two weeks of 1000 words a day, and then to 1250 words a day. “So that the energy in each volume would ramp up”. I have never heard of anyone taking this highly pragmatic approach. Paula Morris chaired, and did a perfect job of providing necessary structure for a conversation that could easily, given Smiley’s range of output and interests, have gone a thousand directions at once and ended up fascinatingly nowhere: instead it was focused and fun.

A passing comment on Trump, too good not to pass on: “When the leader of your revolution is a bobble-head, chaos is at hand”.

I could easily have stopped there and spent the rest of the day processing and reading Carmen Aguirre and Jane Smiley. I moved on instead to Patrick Evans. A nicely representative festival experience occurred while I was waiting for the session to start, writers festivals being where you meet everyone you know and also half the people you don’t. I sat down in the front row with Rachel Barrowman, whose biography of Maurice Gee was on the shortlist for best general non-fiction at the inaugural Ockham New Zealand book awards last Tuesday night. I thought it should have won. I also thought Rachel gave one of the best readings of the night – all the shortlisted writers read for two minutes. I wanted to tell her this, but we kept being interrupted by the shaggy, friendly guy on my left. He wanted to be in on the conversation. He noticed my Metro name tag. “I like Metro!” You know that thing where you’re trying to talk to someone you don’t see very often, and you don’t want to be a jerk to the total stranger who keeps butting in: it was that thing. “You read so well”, I said to Rachel. “Yeah, she does”, said the shaggy friendly guy. How did he know? He was agreeing with everything I said, it was kind of annoying. “So much better than the novelists”, I went on, “the novelists were terrible, didn’t you think they were terrible?” “Yeah”, said the shaggy friendly guy. “I was terrified, though, that’s why”. He was Stephen Daisley, winner of the award for best novel.

I could easily have stopped there and spent the rest of the day processing and reading Carmen Aguirre and Jane Smiley. I moved on instead to Patrick Evans. A nicely representative festival experience occurred while I was waiting for the session to start, writers festivals being where you meet everyone you know and also half the people you don’t. I sat down in the front row with Rachel Barrowman, whose biography of Maurice Gee was on the shortlist for best general non-fiction at the inaugural Ockham New Zealand book awards last Tuesday night. I thought it should have won. I also thought Rachel gave one of the best readings of the night – all the shortlisted writers read for two minutes. I wanted to tell her this, but we kept being interrupted by the shaggy, friendly guy on my left. He wanted to be in on the conversation. He noticed my Metro name tag. “I like Metro!” You know that thing where you’re trying to talk to someone you don’t see very often, and you don’t want to be a jerk to the total stranger who keeps butting in: it was that thing. “You read so well”, I said to Rachel. “Yeah, she does”, said the shaggy friendly guy. How did he know? He was agreeing with everything I said, it was kind of annoying. “So much better than the novelists”, I went on, “the novelists were terrible, didn’t you think they were terrible?” “Yeah”, said the shaggy friendly guy. “I was terrified, though, that’s why”. He was Stephen Daisley, winner of the award for best novel.

Patrick Evans was one of the runners-up for that same award. He’s wryly funny in a cumulatively hilarious not-quite-deadpan style. It is heading towards midnight as I write this and I’ve spent too much energy on anecdotes and overview, so forgive me, these remarks may be about to become more synoptic: which is a crime, because the detail and richness of the conversation, in all of these sessions but especially in this one, was the quality that made being there so wonderful. Evans is a long-time academic, with an easy way with audiences and a highly developed literary intelligence. Chaired by Kate De Goldi – who stayed out of the way except for pin-point brilliant questions as required, and a few lovely bantering exchanges during which it became clear that she and Evans are old friends – he roamed over his work, his working life, the nature of language and its capacity or otherwise to reveal to respond to reality, the nature and vast limitations of human knowledge and its consequences for fiction, and the things he dislikes about New Zealand novels. Wait, what? This pleasant, very Kiwi old guy was breaking the code of national courtesy and actually saying he dislikes things about New Zealand novels?

“Our literature is too middle class. Our official culture is captured by the middle class. Why should a novel be nice? Why should it reinforce what we already think?”

“Our literature is too middle class. Our official culture is captured by the middle class. Why should a novel be nice? Why should it reinforce what we already think? I would like it if we tested boundaries more”. This is an inadequate transcription (I have the worst shorthand of any journalist in New Zealand) of a longer and more unapologetic explication of our national literary faults: it was rather bracing. “Actually though, I’m reading a novel right now, it’s by that bastard who beat me out of the award for best novel the other night”. Daisley, beside me, perked up. “It has a long section from the point of view of a dingo!” Daisley smothered laughter. “I am putting a dingo in my next novel, which is about Janet Frame”. Daisley chortled happily. “It’s a visceral, pared down book, it’s utterly in the moment, every moment. It’s like Cormac McCarthy. Spare and restrained and about something. The bastard deserved to win”.

So now I need to buy Patrick Evan’s new book and Stephen Daisley’s new book. This always happens to me at festivals.

Helene Wong‘s session was next. Before I talk about the excellence of this session, which was, again, sold out, and which moved many of us to tears, and which got a sustained standing ovation, full disclosure – Helene and I worked together for years on the Listener‘s film column. She could not have been a better colleague. For the last couple of those years, I picked up extra money now and then covering for her while she was off working on a mysterious and seemingly very demanding book. The money was very useful. I wondered occasionally if I would ever see the book. I should have known better; Helene finishes what she starts. Robert Muldoon – for whom she was a social policy advisor in the 1970s – once described her in a letter as “tough”, which I would guess was his highest term of praise. Helene mentioned this herself, with entirely pardonable satisfaction, in the process of introducing herself and outlining her life, which is the immediate subject of her memoir, Being Chinese: A New Zealander’s Story. The larger subject is identity, in New Zealand and within the category “New Zealander”, a category from which Chinese New Zealanders have been periodically being excluded ever since the first Chinese immigrants arrived here in the 1860s.

Helene was giving this year’s Michael King Lecture – her title is a conscious echo of King’s classic exploration of his own New Zealand identity, Being Pakeha – so this was the only session of the day with no conversational component: one woman delivering a talk. Much, much higher information density this way. Helene took us through the New Zealand Chinese experience from go to woe, woe having arrived almost immediately. (She quoted this splendidly appalling headline from a 19th century paper: Silly salacious slut snared by slinky slit-eyes.) And then out of woe into assimilation and relative acceptance, helped by China’s status as a bulwark against the Japanese in WWII, and back into woe again: periodic yellow peril scares and upflares of overt racism, right down to the present. (On Andrew Little’s Labour, and their ridiculous campaigns against Chinese property buyers and, god help us all, chefs, Helene said simply this: “Is this who we are? Is this who we want to be?” And I have to tell you, it went through me like a knife. Because no. It isn’t who we should want to be. But it seems it’s still who we sometimes are. I made several rude remarks about those Labour campaigns on Facebook. That was the sum total of my response. I basically did nothing to let Little know he doesn’t speak for me.)

It was a sharp, humane, intelligent lecture. At one point Helene paused to play us Roseanne Liang’s short film Take 3, a hilarious excoriation of racist casting attitudes towards Asian women in New Zealand film and TV. I’ve seen that film several times, two of them at festivals with large audiences. I’ve never seen an audience respond with quite this degree of chastened realisation.

Helene closed by pondering the reception futures waves of immigrants are likely to receive. Better than in the past? Maybe. Not something to count on. But look, she said, at what we stand to gain from inculcating a more inclusive mutual respect for all of our New Zealand identities.

So I bought that book too, obviously.

Vivian Gornick: I am too tired to do justice to Vivian Gornick. She is a pure blast of New York intellectual Jewish fabulous feminist life force: 80-years-old and with that most useful of characteristics people seem to gain with age, the highly developed awareness that it is not always necessary to give a damn what others think. Though she is very polite, and funny, and not at all inclined to take herself too seriously. Jolisa Gracewood interviewed her on stage, and they had a very nice vibe going on: adopted grand-daughter, favourite grandmother. They discussed two books of memoirs, in particular, the structural challenges and emotional dynamics of each: which let in many splendid anecdotes.

A couple of exchanges which must be quoted. Having discussed the qualities of New York, where they’ve both lived, Jolisa asked, “Does Auckland feel like a city to you?”

Flatly, but smiling: “No.” Beat. “It’s a small city like a million others. It has charm. It reminds me of California actually”.

And in response to an audience question, “Is Hillary a feminist?” – a simple, smiling, “Oh no.” Then a beat. “She’s a politician”.

Among the many problems Donald Trump poses the world, one of the smaller ones is that he’s difficult for intelligent people to disagree on.

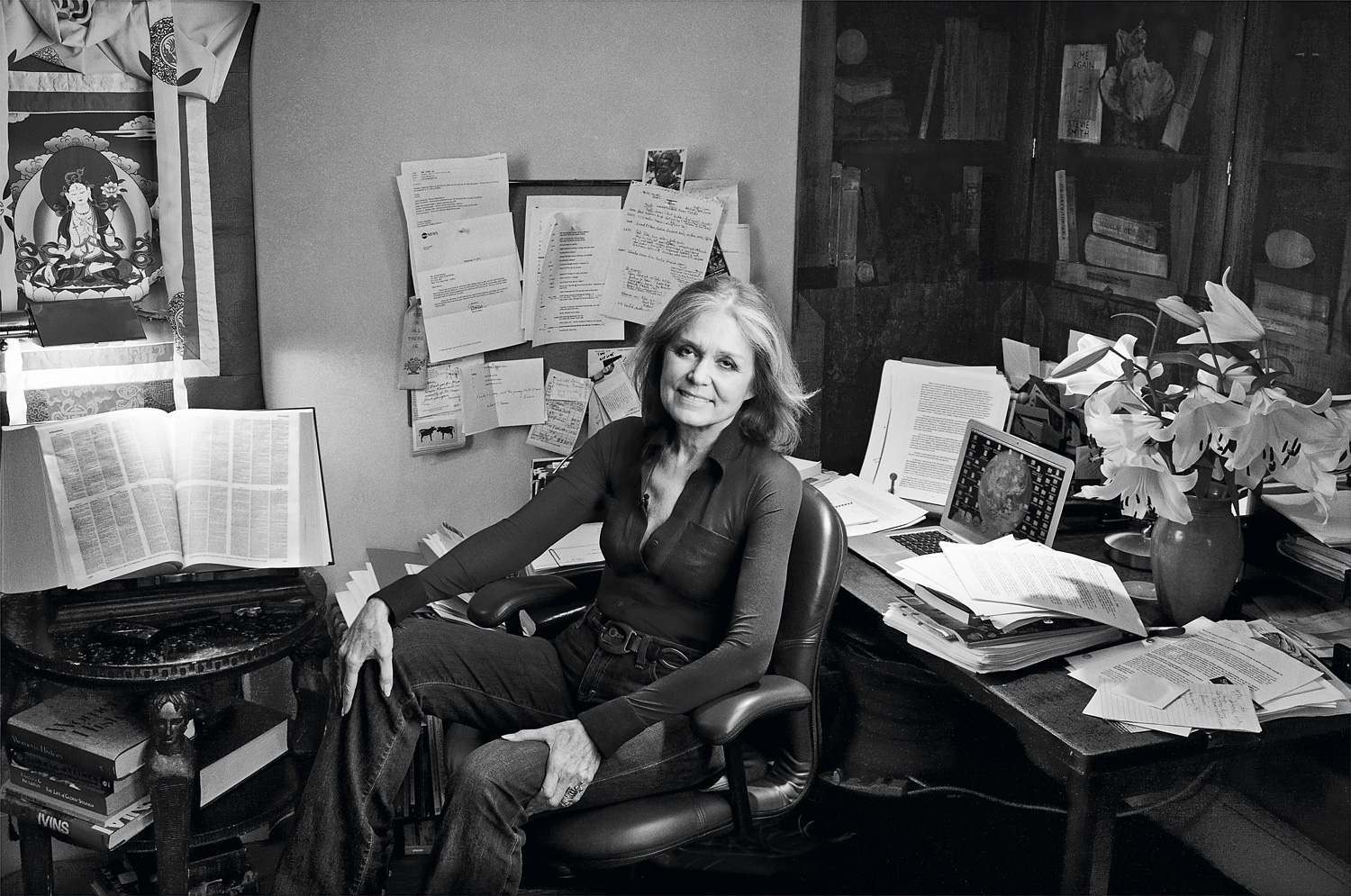

And finally, the panel discussion on the state of America. Chair: Morning Report‘s Guyon Espiner. Panelists: Janna Levin, cosmologist; novelist and critic Thomas Mallon; and Gloria Steinem, who does not need introduction. This was at once highly entertaining, and my one real disappointment of the day. Among the many problems Donald Trump poses the world, one of the smaller ones is that he’s difficult for intelligent people to disagree on. It was good honest fun hearing these three high powered people take turns taking Trump to bits. (Levin: “He is the death knell of critical thinking… we didn’t take him seriously enough soon enough. We made a terrible mistake. And by ‘we’, I mean sane people”. Mallon, a Republican until Trump took the nomination: “I’m less interested in explaining him than I am in vanquishing him”. ) But it wasn’t actually very enlightening. Nor did the wider discussion go anywhere very surprising or deep; the couple of times it began to, both of them involving spontaneous exchanges between Steinem and Levin, Espiner moved things along to the next question.

Espiner was actually a good chair: smart, informed, and often funny. A three person panel on a vast topic with only an hour in hand is a difficult proposition. My basic problem, I decided afterwards, was that I wanted a different and more challenging approach. Steinem is one of the most famous living bastions of feminism and social justice. Mallon is an American conservative. I wanted Espiner to push them past careful courtesy and easy agreement on the awfulness of Trump, and into the endless list of things they deeply disagree on: including the entirety of what the conservative movement in America has done, in the years since Richard Nixon, to make Trump possible. Still, it was a pleasant enough hour. I really, really wanted to go on from it to the A Capella session, a rap-styloe throwdown between Australian slam poet Omar Musa and King Kapisi. But if I’d done that, this blog post would be even longer. Five more sessions tomorrow. Possibly I should go get some sleep.