May 20, 2017 Books

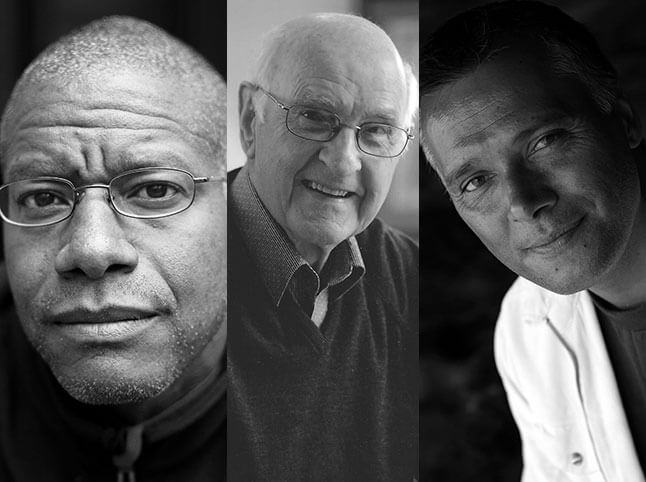

Lloyd Geering is 99 years old and he doesn’t look a day over 90. I am unsure about making him the big get-em-through-the-doors early draw on the first full day of the Auckland Writers Festival, although it’s got ’em through the doors nicely. The main auditorium of the Aotea Centre is a good way towards full. This never used to happen on the first day. People have been chatting and buzzing and jostling; the queue at the coffee bar was no place for the meek. Now the house lights have gone down and a man born in 1918 is walking out onto the stage. I’m afraid for him.

“He did not slip quietly out the door when the meatloaf arrived”, John Campbell tells us. “He looked it in the eye and asked it what it was”. Apparently the Campbell household’s tepid relationship with religion cooled to rigor mortis after the local parish introduced pot luck meals (“it was the 70s”): the notion of meatloaf with the neighbours was more than Campbell’s father could bear. Whereas Geering, faced with the meatloaf of new and difficult ideas, sat down and ate his way to the only heresy trial in New Zealand history. (“I suspect you enjoyed that trial actually”, Campbell says to Geering).

The meatloaf metaphor boasts a spectacular weirdness quotient and a lovely evocative precision, and I don’t think you’d meet it in any other country on earth: it’s exactly how you’d want to kick off a writers festival. But I’m still worried that Geering, whom I’ve admired since I was a teenager, won’t have the cogency of mind he used to have, or for that matter the staying power to do an hour’s talking on stage. I mean, 99 years old. The worry lasts to the end of Campbell’s introduction and then Geering flattens it in about 30 seconds.

This man. Three parts cuddly national grandfather, six parts thorny intellectual iconoclast, and still quietly, merrily himself. “To hold a set of beliefs is really idolatry”, he says while discussing the meaning of faith. “The universe has no purpose. But we human beings are purposeful”. He says, “God is a set of values”. These are not easy ideas. He’s cogent and direct in discussing them, neither aggressive nor apologetic, one of the great public intellectuals New Zealand has produced. On Thursday night, at the festival’s opening gala, AWF director Anne O’Brien gave a brief speech on the widening cultural divides we’re seeing across the world at the moment. “We won’t always agree with each other. Indeed why should we expect to? We must find ways to engage those with whom we disagree…” My initial response to this was that it misunderstands the problem — engagement takes two, and if one of them voted for Trump and thinks climate change is a hoax, I don’t like your chances — but Geering makes me think again. He has spent decades patiently explaining himself to people who in many cases didn’t want to know. “The heart of Christianity, for me, is loving one’s enemies… that’s very difficult indeed.”

And Campbell. Do we have another journalist half as good at sharing his love for what he does? He’s having a ball up there – he’s delighted to be on this stage with this man — and the pleasure is so obvious you could overlook how hard he’s working. He keeps the conversation moving, he unobtrusively rescues Geering the handful of times his failing hearing lets him down, he does no more of the talking than he needs to, and he does all this with the happy beam of a man getting to meet one of his heroes. We get Geering’s memories of the day the bomb fell on Hiroshima, and we get his fear that climate change and overpopulation mean “there is a doomsday coming”: and yet this is a sweet hour.

He did rather enjoy that heresy trial. “Everything I’d said had been said by others… it was just that people hadn’t kept up with their reading”. Not a bad note for the start of a writers festival. He gets a sustained standing ovation as he leaves the stage.

I was going to head to the Anne Enright session next, but the woman sitting next to me for Lloyd Geering tells me I want to go to Stan Grant instead. I have no idea who Stan Grant is, and Anne Enright has won the Booker, so I troop downstairs to the Stan Grant session. There are more things happening at this festival than one person can keep up with, by a factor of roughly four. So go where the buzz is, and try the people you haven’t heard of: it’s a pretty good rule. It certainly works this time.

Though I seem to be the only one who hasn’t heard of Stan Grant. The Lower NZI room is packed out. It turns out Grant – who in a nice piece of synchronicity is chaired by Carol Hirschfeld, John Campbell’s old news reading partner – is an Australian journalist. He’s worked for CNN. He’s also a Wiradjuri tribesman, and he talks to Hirschfeld about growing up dirt poor, living with casual and non-casual racism, what Australia has been and what it is. They also discuss the culture of newsrooms, reporting from trouble zones, and PTSD. Grant is extraordinary across the board: eloquent, succinct, deeply knowledgeable, insightful, dignified, able to discuss complexity without oversimplifying. The woman who told me to come see him had been to Wednesday night’s panel discussion on global affairs, where she found he was substantially the strongest and most interesting voice; and from passing references here and there it’s obvious he could talk about Brexit or Syria or the strengths and weaknesses of the Chinese economy with clarity and authority. But mostly the subjects are his life and his country, and he’s completely absorbing on both. He’s also insistently optimistic, which from a person who sees and acknowledges all the reasons not to be is particularly powerful: when an audience member cites John Pilger’s documentary Utopia, with its litany of all the many ways Australia is still mired in its racist past, Grant lists the ways things have improved in his lifetime. He isn’t saying things are great. He’s saying don’t wallow in the negatives: work on changing them. “A nation”, he says, “is unfinished business”.

Hirschfeld is a good choice of chair here: seasoned journalist, Maori with a white Australian father, she has an easy rapport with Grant and a sure sense of where the hinges are in his story. The logic of the chairing choice for my next session, with essayist/novelist/art historian/one-could-keep-adding-labels Teju Cole, is a little harder to fathom: the session is put in the hands of the Melbourne-based American writer and critic Kevin Rabalais. Rabalais is a smart if not particularly relaxed or relaxing chair; he knows Cole’s work and he asks good questions, though his “and now I shall ask my next carefully prepared question” style doesn’t do much to promote a sense of natural flow. What surprises me about having him in the chair is that, listening to one person with no roots in New Zealand interview another, I feel curiously excluded: it’s like listening to American public radio. I love listening to American public radio. But I hadn’t realised how much the presence of New Zealand chairs grounds sessions with international writers in local experience. Take that away, and I find I’m annoyed. The implication that we don’t have local chairs able to keep up with Cole is not especially pleasing either.

Cole – his first name is pronounced “Tay-ju”, which I’d never figured out – does take some keeping up with. As Rabalais comments at one point, he speaks in paragraphs: language unspools from his tongue in elegant ribbons. He reads three extracts from his books, one of them a series of 140-character novel rewrites he composed on Twitter, in which great literary works are cut short (very short) by the drone assassinations of their protagonists. It’s chilling. It’s brilliant. He talks about the lack of the conventional markers of essaystic personality in his work, the way he describes scenes rather than building arguments: “Description is itself an ethos. To simply describe already shifts something in the world… what I have faith in is that somewhere in the world there are people who will find something to hold onto in these descriptions. If I describe something to you, your imagination has to get involved”.

My own imagination is very involved right now in the business of trying to assemble Cole into a simple enough personality for me to describe, but I’m finding I can’t: the problem of delineating him, after a single hour of conversation broken up by multiple readings, defeats me. He projects as the subtlest and most complex person I saw today. I’ve read several of his essays and my main response — this is embarrassing to admit — is a slightly chilled withdrawal. He has a powerful literary mind. But he eludes me.

A couple of random comments I particularly liked from the session: “In the early years of the 21st century I wrote a book that by the standards of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Mrs Dalloway was not very experimental; it was a century out of date. But most of the other novels published in that period were 150 years out of date. So I was seen as very avant garde.”

And this, in response to a PhD student’s somewhat wordy question from the floor: “When approached by a graduate student or an academic I sometimes feel like a calf being approached by a butcher. All you can hope for is skill”.

Waiting in the Aotea foyer for the doors to open on the next session, which was to be with this year’s Booker winner, Paul Beatty, I was struck again by the brute size of the crowd. The Beatty queue was the grand winner of the day’s queue-you-don’t-want-to-be-at-the-back-of competition. I couldn’t even work out where the back was, there were snarls and coils and intertwinings going on. While I was standing there admiring it, and thinking back three or four years to the days when the Friday AWF sessions were quiet little baby sessions before the big crowds of the weekend, a vaguely familiar guy wandered past. He was looking at the queue too. He seemed mildly alarmed. I realised after a moment that I knew him from the Booker press releases. It was Paul Beatty.

I’m not sure what Beatty was doing in the foyer just before his session opened, rather than safely off in a green room somewhere, but that look of alarm was a pretty good herald of what followed. Beatty is a very easy guy to like, partly because he seems so very unsure of himself. I lost count of the number of times he apologised to Paula Morris, his session chair, for one incomplete answer or another, or for saying something he expected her to dislike, or find inadequate somehow. He interrupted his own reading at one point to say, “I can’t believe I’m doing this. I gotta get another job”. This just after reading a character’s reference to the notion of sticking one’s hand up Godzilla’s asshole. His work is profane in the extreme, funny, dark, and he seemed to be continually going back and forth between embarrassment and unapologetic insistence that this is who he is and this is how he writes.

He also struck me as highly driven. When Morris asked him about his turn to fiction, after his early writing career as a poet, he said, “Poetry’s the dark side, really…” Why? Because as a poet you have to do a lot of public performing. And he’d found himself developing a following, and starting to write with an eye to their reactions. The day he noticed himself writing a line and thinking, “Oh they’re going to like that!”, he quit.

The thing is, poets don’t have to perform. It’s just that they tend to get read more if they do. Likewise, Booker winners who clearly feel uncomfortable on stage don’t have to go on stage. And yet Beatty, who walked away from the poetry reputation he’d made for himself as soon as he noticed it changing his work, is now out on the festival circuit presenting his new work to the world. He doesn’t seem to enjoy it very much. I liked him a lot.

That, if you’re counting, is four one hour sessions, each of which felt more like a 30 minute session: they go by fast. The half hour gaps between them hardly seem to exist at all. You run to the loo, grab some food or a drink, check your messages, talk to any friends you bump into, and get into the next session fast enough to get a good seat. It comes as a shock when you notice it’s now 4pm; the feeling is as if a giant hand has pushed you forwards through most of a day without you getting to experience duration.

I noticed the hour mostly because this was the first time all day I’d stepped outside. I was going to the Heartland Festival Room, the new temporary venue the festival has had thrown up in the middle of Aotea Square, to hear Nick Bollinger talk about his 70s rock memoir, Goneville. Bollinger is my favourite New Zealand music writer, and a familiar voice from his regular RNZ show The Sampler; so initially it felt very easy and pleasant sitting in a room listening to him, and then it became fascinating. So much about our emerging music scene in the 70s I didn’t know. The involvement of the breweries in constructing and funding venues, in order to sell beer more successfully after the end of 6 o’clock closing forced them to change their marketing approach, ie, to start having one. The emergence of an alternative performance scene on campuses. The tensions between these two venue systems. And the ways musical influence flowed, or failed to, in the days before easy access to international albums. “Someone might have gone overseas and come back with a new album, and you’d travel across town to hear it… and sometimes bands were being influenced by hearing these albums, but more often I think they were influenced by the idea of what they imagined overseas bands were doing, based on things they’d heard whispered about”.

Final session of the day: also in the Heartland Festival Room, which becomes a slightly less good venue after 5.30 on a Friday, as exterior noise in the Square starts to ramp up. (One writer on this panel interrupted her reading at one point to ask if someone was shouting at her; it was just someone outside yelling to a friend). A four-writer panel: the four Ockham New Zealand Book Award winners, in fact, as anointed on Tuesday evening at the awards ceremony. The idea was to put them in a room and have them debate the question of a writer’s duty to their society. So, best non-fiction: Ashleigh Young. Best poetry: Andrew Johnston. Best illustrated non-fiction: Barbara Brookes. Best fiction: Catherine Chidgey. Frances Walsh chaired, and did a pretty decent job, by which I mean the panel was something of a mess, and entirely inconclusive, but many interesting things were said, and more overall coherence couldn’t really have been expected. Four person panels are an organisational nightmare, and this one had been put together in the three days since the awards, with all four writers shouldering other festival duties. I did think that asking all four of them to read from their work was rather beside the point, and cut into the already inadequate discussion time grievously.

A writer’s duty to their society, if you’re interested, is… to write. Truthfully. Not to preach. Perhaps occasionally to stand up and speak truth to power, though there was general agreement that the way Eleanor Catton was treated by our politicians and media when she tried this is not a great incentive. “You are all in a relatively privileged position because of the attention you can command”, said Walsh. “The question is what you do with that”.

Metro’s David Larsen blogs the Auckland Writers Festival 2017. You can read his second instalment here.