Nov 23, 2015 Books

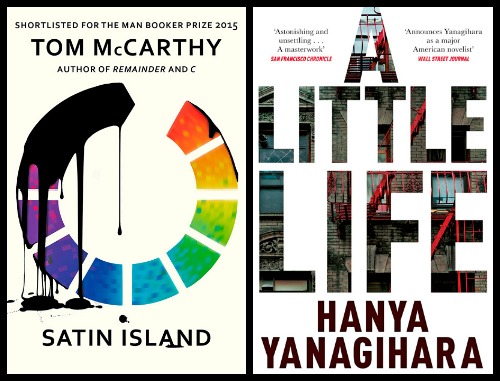

Two books that didn’t win the Booker; but got pretty close.

This article was first published in the November 2015 issue of Metro. Main image: Author Tom McCarthy.

Satin Island

Tom McCarthy

(Jonathan Cape, $37)

In 2006, the architectural theorist Eyal Weizman published an essay that described how the Israeli Defence Forces had turned away from conventional military logic for their urban warfare tactics.

Instead, according to Weizman, they were drawing on French semiotic and poststructuralist philosophy. IDF generals were reading Deleuze, Guattari and Debord. They were talking about rhizomes, the differences between smooth and striated space, and how they could critique their “existing paradigms”.

It was leftist theory given violent form; though rather than being used to smash the state apparatus, as many of the 1968 generation had hoped, it was propping up Israel’s claims to the Palestinian territories. As Weizman wrote, “If, as some writers claim, the space for criticality has withered away in late 20th-century capitalist culture, it seems now to have found a place to flourish in

the military.”

I’ve got no doubt the novelist Tom McCarthy knows Weizman’s work. They’re the same age. They both live in London. And they’re both members of a radical generation in their forties — others include the artists Hito Steyerl, Omer Fast and Trevor Paglen and the writer Maggie Nelson — who’ve managed to absorb French theory, process it, and spit it out in beautiful new shapes that examine today’s defining political and cultural questions.

McCarthy’s marvellous, layered novel Satin Island, shortlisted for this year’s Man Booker Prize, is his best example yet. The book’s hero, simply known as “U” (an unambiguous nod to Kafka’s “K”) is, like those Israeli generals, a devotee of deconstruction, though rather than putting it in the service of the military, he works for a different oppressive force — giant corporations. He is his company’s in-house anthropologist; having once had a promising academic career, he now finds himself coughing up half-baked connections between Deleuze’s concept of the “fold” and Levi’s jeans — and earning acclaim for it.

He’s an anthropologist searching for his tribe. Not that he’s miserable about it. He gets to travel. He has money. He has a decent, uncomplicated sex life. But hanging over him is an impossible task.

U’s boss is a man called Peyman, a faceless think-tank guru who sells ambiguous aphorisms to governments and global mega-brands. Equal parts Tyler Brûlé, Pussy Riot and Derek Zoolander, Peyman promises a kind of revolutionary thinking that never actually arrives.

He’s hired U to write “The Great Report”, a theory, basically, of everything. Which, of course, U can’t do. Instead, he puts most of his creative and analytical energy into reveries about future accolades that’ll place him on the same anthropological astral plane as his hero, Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Though very funny in places, this novel definitely isn’t satire, and the text has an incredible lightness compared to its theoretical sources. The only thing that makes it occasionally hard to read is that U is kind of a dick — something even he realises, particularly when he discovers that his booty call, Madison, has a far more complex and anarchic past than he does.

In the London Review of Books last year, McCarthy smacked down “the naive and uncritical realism dominating contemporary middlebrow fiction”. He sees himself as part of a different, avant-garde trajectory — one that runs from Kafka to J.G. Ballard, in which technology and unseen hands shut us down so brutally that we finally have to turn to violence for physical release.

It is one of the most ambitious and quietly revolutionary novels published in years.

Which sets the bar pretty damn high. But in Satin Island, he clears it easily. It’s a superb examination of corporate culture’s warm and inescapable tendrils. It’s also a super-weird tale of Vanuatuan cults, oil spills, unexplained skydiver deaths, hub airports, Parisian rollerbladers, radical cancer therapies, New York rubbish dumps and the anthropological implications of 9/11.

It may not be a Theory of Everything. But it is one of the most ambitious and quietly revolutionary novels published in years — a remarkable, crystalline portrait of the way late capitalism has turned us all into a single, voiceless tribe.

A Little Life

Hanya Yanagihara

(Picador, $37.99)

Review by Kiran Dass

Hanya Yanagihara’s shattering and incendiary second novel, A Little Life, also shortlisted for the Booker this year, is a brilliant firecracker of a book. It’s also one of the most emotionally exhausting and headspinningly upsetting novels I’ve ever read.

What a blast of fresh air to read a novel that has been written with not only great care and craft, but also with a staunch backbone. No compromise here.

What begins as a seemingly carefree narrative about four bright young friends in New York jolts itself into something altogether much darker. In many ways this is simply a beautifully observed study of tender friendships between men, but at the heart lies an examination of the effects of physical and emotional abuse and the lasting effects of the trauma attached to the fallout.

Forget your overblown puffed-up Franzens, this is the real deal.

JB is a narcissistic artist; Willem, a handsome actor; Malcolm, an architect; and Jude, a successful but haunted lawyer. Jude’s backstory is slowly revealed to us and while deeply sad, the insights are gorgeous and superbly rendered, as are the quiet and gentle dynamics between Jude and his circle of friends.

Relentlessly heavy, A Little Life is dense and completely immersive — the narrative is crafted with such finesse that the world Yanagihara creates is inescapable. From trauma to empathy, everything is amplified and turned up to 11. The way Yanagihara has so deftly externalised Jude’s emotional inner life is remarkable. Deeply sad, yet filled with insights, A Little Life is an unforgettable literary experience.

Forget your overblown puffed-up Franzens, this is the real deal.