Nov 28, 2018 Art

Auckland Museum is forging a path far beyond its British museological inheritance.

I took it, too, when I was their age, or near enough to it, and saw the Maori and Pacific halls, the plaster copy of ultra-muscly Laocoön and his sons battling snakes, the endless names of dead soldiers, and, of course, Centennial Street, with its weird displays of dolls and sweet shops and general air of terrifying ancientness and technological impoverishment.

Nothing changes; everything changes. The museum, that giant neoclassical edifice built on colonial foundations, is still stolidly in the same place and still seems to whisper, at least as you enter its traditional front doors, “Hush, child; this is a house of dead things”. But Centennial Street is gone, and most visitors now enter through the far flashier and welcoming south atrium. And the purpose of my son’s trip wasn’t a fusty walk-through of Auckland’s past, but a unit on Te Tiriti o Waitangi: my son and his classmates were there to learn how to be, as the museum’s inhouse educator put it, “active Treaty partners” — to engage in the responsibilities of biculturalism.

This was, I thought, a pretty abstract pitch to a group of over-excited juniors. But certain things happened which struck me as definitively different from what seven-year-olds might have done 30 years ago. The first was their understanding of how to behave as they entered Hotunui, the meeting house at the heart of He Taonga Maori, the Maori Court. They understood implicitly that they were inside his body and that this came with a particular set of behavioural obligations: not so much drilled into them on the bus beforehand as absorbed through a daily karakia, learning their own pepeha, and even from the spontaneous haka my boy often breaks into during his post-dinner energy burst.

Once inside Hotunui, a second revelation took place: the children were allowed to handle taonga, and to guess at what they’d been used for: hunting and fishing and cutting tools that brought hilarious responses, but which nonetheless made things utterly, tangibly real. The conservation-grade glass was gone, and with it the distance between my son, his Iranian, Chinese, Zimbabwean, Tongan, Samoan and Korean classmates, and the first people of Aotearoa.

This idea of touch, accessibility and connection is the core of Auckland Museum’s preparation to become a “Future Museum”. Forgiving them the corporate neologism, this is an essential transformation for an institution with such a thoroughly British museological inheritance. And the heart of this change is “Te Awe”. Having begun in 2013, it is a vast stocktake and digitisation exercise. Every one of the museum’s 10,000 Maori taonga is being examined, photographed, researched and, if necessary, recategorised or flagged for conservation.

As Bethany Matai Edmunds, the museum’s associate curator, Maori, explained to me, the first half of the project, from 2013 to 2016, was to document everything within the whakairo — carving — stores. Even that, she pointed out, told a colonial story of the way things have long been set up, with a storage division between carving and weaving (with carving, in classical museology, always being held up as the superior, masculine artform: an orthodoxy the groundbreaking 1980s exhibition Te Maori maintained) based on old clichés of “male and female, hard and soft”, and so on.

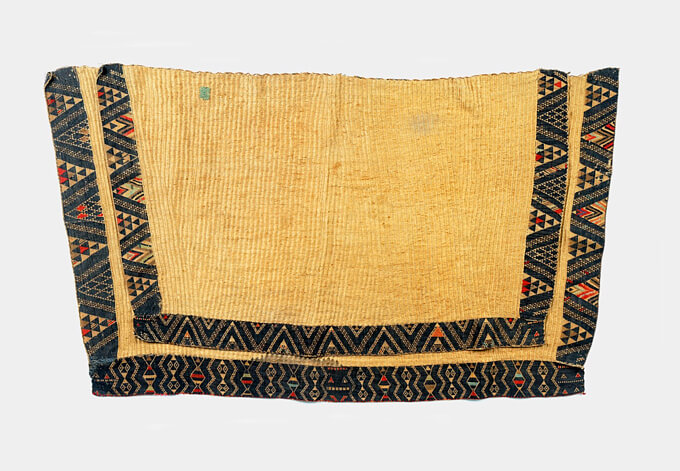

On the day we met, Edmunds and her colleagues were facilitating a meeting in the Te Awe project room. A group of women were seated around a table, on which various kete were spread. The women had been brought together from around the country, and had been selected, Edmunds explained, for geographical spread, but also because they were regarded as supreme experts. Among the working group were artist Maureen Lander as well as master weaver Kahutoi Te Kanawa and her sister Rangi Te Kanawa, weaving conservator: daughters of the legendary weaver Diggeress Te Kanawa.

On a whiteboard was a record of how the conversation was going. In essence, the women were working together to agree terms: specific definitions for the different kinds of kete in front of them. The short-term result of this was that they were creating a depth of knowledge around the objects that acknowledged the nuances both of their utility and their makers; a step towards equivalence with the male-dominated and museologically privileged field of whakairo. The long-term effect will be that, in this act, they are changing how the museum will conserve and group woven objects. It’ll cause an online revolution, too, with new accessibility for researchers, iwi and whanau who directly connect to the objects, and, frankly, anyone else curious enough about them.

As Te Awe expands and moves onto the Pacific collection, the different forms of knowledge it’s creating about taonga — familial, conventionally academic, matauranga Maori, decolonial — are likely to have a dramatic impact on how we actually experience them in exhibitions. There’s already talk about breaking down age-old barriers between Maori and Pacific, Maori and colonial, customary and contemporary. There’s a weird exhilaration in thinking that, exactly 250 years after London’s Royal Society sent James Cook to the South Pacific, a project like Te Awe — which doesn’t look to the past but utilises new technologies to create a knowledge base for the future — may help us make exhibitions that absolutely speak of, and from, here.

Obviously, this transformation is as an unwinding of colonial legacies. But there is something else going on, I think, which is almost as significant. A particular view of globalisation my generation wholeheartedly embraced is now coming apart at the seams — the Blairite idea that the world was our oyster and that we could simultaneously speak platitudes about postcolonialism and redress while also believing in our hearts that there was no “local”; or if there was, it was really just a shorthand for “provincial”. Such a world view was, I now feel, just one more facet of the aspirational capitalism that has ended up breaking the world, rather than fixing it.

My son’s generation is going to have to deal with globalisation’s collapse, and with it, going to need a renewed “sense of place”. This is formed in the complex interaction between our bodies and objects, in the broadest sense — tools, art, the buildings we live in, each other: life — real, actual life — just beyond the borders of ourselves. As I watched the kids looking up to see Hotunui’s ribs in the rafters, then a few weeks later saw a group of women gently debate the names of woven baskets, I thought that the solution to the failures of the vast technological civilisation we’ve built, worshipped and already started to destroy in less than 20 years may be much closer to home than I thought.