Dec 26, 2016 Art

Few people know Anne McCahon, the wife of Colin, was also an artist in her own right. To mark the first solo exhibition of her work, family members tell Metro about the couple’s creative partnership.

A classic example is the case of Louise Bourgeois, the celebrated French-American sculptor who was a contemporary of Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and produced work her entire life but famously didn’t make her debut on the international scene until New York’s Museum of Modern Art mounted a retrospective when Bourgeois was 71.

Last year, when London’s Tate gallery presented shows by leading British modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth and abstract expressionist painter Agnes Martin, they were couched in terms of delivering long-overdue recognition to the artists’ careers, establishing their position alongside their male counterparts.

So when I heard that the McCahon House Trust was presenting the exhibition A Table of One’s Own: The Creative Life of Anne McCahon at Titirangi’s Te Uru gallery, I admit I lurched towards the narrative of the overlooked, downtrodden female artist. Here was a woman who topped her class at art school in Dunedin, was an integral member of a group of young modernists whose names are etched in New Zealand’s art history books, started an all-female studio with Doris Lusk and yet has never been granted her own solo show. The injustice was surely only amplified by the fact that Anne McCahon was married to our most significant artist of the modern period, Colin McCahon.

What I found was more nuanced than that. Anne’s is not so much a story of sacrifice — although that certainly comes into it — but more one about the reality of life’s choices. And that, we can all relate to.

In Auckland, the first place to go looking for Anne is at 67 Otitori Bay Rd, French Bay, Titirangi. This was Anne and Colin’s house when they moved to Auckland in 1953 with their four young children and is now a museum run by the McCahon House Trust. It pays homage to the life and career of Colin, but when you walk through the door of the tiny wooden house surrounded by the vertical thrust of kauri trunks, you are immediately struck by its humble domesticity. You enter the cramped wooden house straight into Anne’s space, the kitchen.

When the museum opened in 2006, the occasion was marked with an exhibition of Colin’s work entitled The Titirangi Years. A decade later, the trust has deemed it time to tell Anne’s story — largely due to popular demand. Visitors to the house often ask of her, as do the artists who rotate through residency next door. “Many of the artists who come through feel the mana of Colin McCahon but they also request to know about Anne,” says Diane Blomfield, executive director of the McCahon House Trust.

Recent resident artists Tiffany Singh, Bepen Bhana and Fiona Pardington have all made works influenced by Anne’s presence.

“I think that she actually consciously made the decision not to compete with him as an artist.”

“I felt she was overshadowed by Colin,” says Singh, who created an artwork dedicated to Anne with blue hydrangeas — Anne’s favourite colour — as part of her residency project. “There is not enough awareness of her as an artist.”

While the Te Uru exhibition is solely about Anne, it’s impossible to untangle her work from her relationship with Colin. “It’s a love story,” says Blomfield. “The more we look into it, the more we realise that.”

Little has been written on the creative output of Anne McCahon. She is, of course, present in New Zealand’s art history books through Colin, but unpicking her story means digging out scattered mentions from the index pages under subheadings likes “marriage” and “children”, and there is scant evidence of her artistic achievements.

Linda Tyler, associate professor of art history at the University of Auckland and the curator of the Anne McCahon exhibition at Te Uru, was one of the first researchers to investigate Anne’s story for a chapter in Deborah Shepard’s 2005 book about artistic relationships, Between the Lives: Partners in Art. Tyler called the chapter about Anne, “I did not want to be Mrs Colin”. In it, she detailed how marriage to Colin and the demands of motherhood had “exhausted Anne’s creativity”. There was only room for one artist in the family, wrote Tyler, and that was Colin.

Tyler’s view of Anne’s situation has since softened. “The slant I took with the chapter was that she’d been overlooked and forgotten and maligned,” says Tyler. “Now, because I know a little bit more, I think that she actually consciously made the decision not to compete with him as an artist.”

Anne, nee Hamblett, met Colin in 1937 at King Edward Technical College in Dunedin. Born in 1915, she was four years older and already in her third year when he began studying at the art school. Colin was one of three male students in the class and his first encounter with Anne and her circle made a lasting impression. In a biographical essay in Landfall, Colin wrote about “superior and aloof” female students who somehow got away with smoking despite the “no smoking” ban. “Later on,” wrote Colin, “I married one of the superior girls (first met and seen through a barrier of tobacco smoke and Brahms on a portable gramophone).”

Anne’s upbringing was generally one of obedience but she did have a rebellious streak. She was born in Mosgiel and lived in Dunedin from the age of seven when her father, WH Hamblett, became an Anglican vicar. The second oldest in a family of six children — three girls and three boys — Anne, with her sisters, was expected to take on household roles from her early teens, says Anne’s daughter Victoria Carr. It fell to Anne to take charge of the food and cooking, and she was known for her culinary skills all through her life. The sons were exempt from household duties.

While at Otago Girls’ High School, Anne excelled at art and had strong role models in her teachers Margaret Shearer McLeod, a portrait painter and botanical illustrator, and Myra Kirkpatrick, who encouraged her students to explore applied arts such as set and costume design and book illustration. With their support, Anne enrolled at art school and achieved high grades, winning a fee-paying scholarship in her second year and the art school prize in her final year.

At the end of her studies, Anne set up a studio with a group of other new artists — including Colin McCahon, Doris Lusk, Max Walker, Morris Kershaw and Mollie Lawn — above a pharmacy in Dunedin’s Princes St. It was a very productive period. In 1937, she exhibited four oil paintings at the Otago Art Society, including Vicarage Bed and Poppies, which both feature in the Te Uru show.

Jessica Douglas, who is a researcher for the Te Uru exhibition and is writing her thesis on Anne McCahon for a master of arts degree at the University of Auckland, singles out Vicarage Bed as a key work. It depicts the iron bedstead in Anne’s bedroom when she was still living with her parents. The painting’s low, non-traditional perspective and flecked highlighting demonstrate the influence of post-impressionism, particularly Vincent Van Gogh’s painting The Bedroom (1888).

Anne’s friends obviously also admired the work. Douglas notes that 40 years later, Doris Lusk painted a watercolour portrait of artist and critic Rodney Kennedy sitting on a chair with Anne’s Vicarage Bed hanging on the wall behind him. “It showed he really liked the art work,” says Douglas.

“Certainly if you wanted a good painting in those days you would have gone to Anne to do it.”

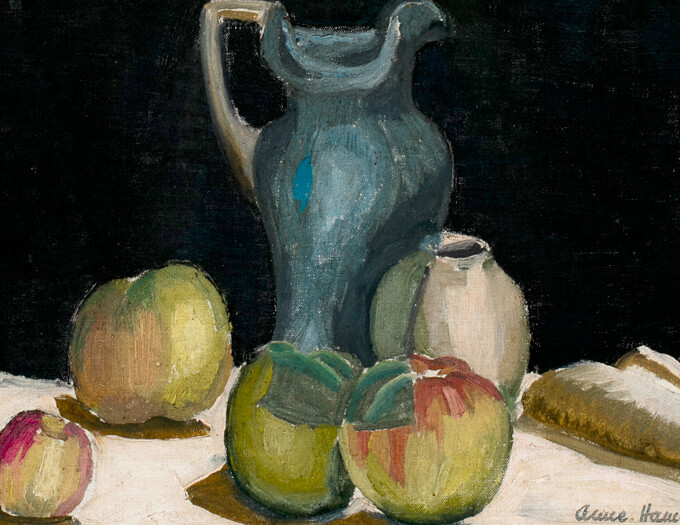

Poppies is a bold still life of a vase of flowers with strong modernist qualities. The glimpse of two paintings in the background recalls the work of the great modern master Paul Cézanne. Anne has flattened the painting’s perspective and moulded the flowers’ petals in thick, obvious, scarlet brushstrokes. Douglas says this marks a conscious shift from elegance and beauty towards a harsher treatment of subjects that was characteristic of the young modernist group.

Carr notes that her father considered her mother to be a better artist than he was in terms of skill. “Certainly if you wanted a good painting in those days, you would have gone to Anne to do it,” she says.

Despite her successes at art school and in her burgeoning career as an exhibiting artist, Archdeacon Hamblett clearly wasn’t enthusiastic about Anne’s chosen path. After she graduated from art school, he enrolled her at Dunedin Teachers’ Training College, presumably to set her up with a more respectable, stable profession. Little did he know that Anne would regularly skip class in order to go to the studio. It wasn’t until Anne reported sick for examinations that he discovered she had been sneaking off to continue her art.

Anne’s quiet determination prevailed. She continued to paint, and became a central figure in the group of young Dunedin painters and also an early and staunch supporter of Colin’s work. At the end of 1939, Colin entered a large work in the Otago Art Society annual exhibition and it was rejected, the first of many humiliating rejections he would endure from the art community. Anne was one of several young painters who removed their work from the exhibition in protest. Eventually, Colin’s work was reinstalled.

By now, Colin had convinced the “superior” older woman of his charms, and Anne and he were an item. Colin had visited Anne’s parents to “walk her out”. That summer, Colin and Rodney Kennedy went north to see Toss Woollaston and gave up their shared studio, leaving Anne to set up an all-female studio with Lusk and Lawn. It was a busy time artistically for Anne, who exhibited six works that year at the Otago Art Society, selling most of them for the impressive sum of twenty guineas ($42, equivalent to $2000 today) and receiving positive reviews from art critics.

Colin and Anne married in September 1942 in a ceremony conducted by Anne’s father at St Matthew’s Anglican Church in Dunedin, but not before overcoming some obstacles. In an interview with the Listener after Colin’s death, Anne revealed she refused his first proposal, saying that at four years her junior, she thought him too young to marry. But Colin “never took no for an answer”. He searched the second-hand shops for a gift and presented her with an antique bracelet with seven moonstones. “I would not take it,” Anne told the Listener. “I was horrified, aghast. I did not want to be Mrs Colin.” She did eventually accept the bracelet, and kept it her entire life.

Paintings and sketches show Anne and Colin sharing ideas and influences in their work.

Archdeacon Hamblett was less than enthusiastic about the union. Perhaps concerned about Colin’s ability to provide for his daughter, he insisted Colin produce £80 (roughly $7000 today) before he would give his blessing.

Anne’s father’s concern was well founded. The wedding marked the start of many financially precarious years as the McCahons struggled to find work that would support their art and growing family. Shortly after their marriage, they lived in Pangatotara, near Motueka. Paintings and sketches of Pangatotara landscapes from this time show Anne and Colin sharing ideas and influences in their work. But the couple were soon forced to separate when Colin went to Wellington to work as a gardener at the Botanic Gardens, and Anne returned to her parents in Dunedin for the birth of their son William in July 1943. A touching pen-and-ink sketch of William as a baby in a gown with smocking detail is in the Te Uru exhibition.

Victoria Carr has a letter her mother wrote to Colin at the time in which Anne describes the baby clothes she has made for the new arrival. “It’s just a page and it’s very sweet,” says Carr. “It was an important thing. She was preparing to be a mother for the first time.”

Living in Dunedin with the support of her parents meant Anne was able to put her artistic talents towards a new creative pursuit as an illustrator. In 1943, author Aileen Findlay invited Anne to draw pictures for her children’s book called At the Beach. This kicked off a 16-year career as an illustrator for books and journals that contributed much-needed income for the family.

Reunited in Mapua, near Nelson, in 1944, Anne and Colin collaborated on a delightful series of ink and watercolour works called Pictures for Children. The paintings’ simplified hills and harbour landscapes, which can be attributed to Colin, are brought to life by Anne’s playful line drawings of boats, trains, buses and cars.

Tyler calls these works “the artistic high point in the McCahons’ painting relationship”. The couple were working as equals. But it wasn’t to last, and over the next, very unsettled, few years, Colin’s work began to take precedence.

“Anne decided Colin was the genius and it was her role to support him,” says Tyler. “I feel like she probably thought that she didn’t have that degree of originality. There are two versions of the Dunedin Botanic Gardens — one she did and one he did. He was tending more to greater abstraction and being more adventurous than she was. I think she pretty much made the decision that he was the better artist, or more remarkable artist.”

That small oil on hardboard painting of trees in a wintry landscape, The Park (1945), would be the last Anne ever exhibited.

Carr agrees there would have been a point when Anne made the conscious decision to forfeit her career for the sake of Colin’s. “She says in a letter that we have that she had no regrets because she was so sure of Colin’s work,” says Carr. “The other thing was she felt that Colin was the one who had something to say, whereas her works [mostly domestic interiors and landscapes] didn’t have something to say. People nowadays would argue that quite differently.”

Not that she would have had much time to paint. Anne had two more children in Nelson — Catherine in 1945 and Victoria in 1947. In 1947, the family moved to Colin’s parents’ house in Dunedin. Colin moved to Christchurch in early 1948 to board with Doris Lusk and her husband, Dermot Holland. The last McCahon child, Matthew, arrived in April 1949, and the whole family moved to Christchurch in mid-1949 to a rented house by the railway yards.

Somehow, even with four small children, Anne managed to keep working creatively. In 1950, Roy Cowan, the new art editor of the School Journal, commissioned her to contribute illustrations. Always filled with a strong sense of character, Anne’s fun, lively drawings for children’s stories such as “The Obstinate Turnip” and “Apple Dumplings” decorated the Journal’s pages for the next 20 years. “Her creative life, after she had children, became something she did on kitchen tables,” says Carr.

Anne continued on with illustration work after the family moved north to Titirangi and finally had some sort of stability. Or at the very least, could be together. Colin bought the tiny cottage in the Waitakere bush in 1953, after being promised a job at the Auckland City Art Gallery. It’s New Zealand art folklore that when he turned up, there was no job and the only work director Eric Westbrook could offer him was as a cleaner. In fact, this sorry state of affairs didn’t last long and Colin was soon promoted to custodian of the paintings, and became the gallery’s deputy director in 1956.

Regardless, these would have been hard, lonely years for Anne out in the bush. Colin went to town early on the bus and was often not back until late. Anne was left alone at the house with the young children, far from her South Island support network.

Fortuitously, when they moved north, Anne’s paintings were stored with Colin’s parents, by then living in Geraldine, as there was no room for them at the French Bay place. Ethel McCahon, obviously recognising their merit, bequeathed the works to the Hocken Library, thus preserving them and ensuring they became a part of Dunedin’s public art collection.

With a lack of space in the Titirangi house, Colin took over the living areas to paint. Anne’s creative output was more domestically focused. Despite the family not having a lot of money, she made sure the children were always beautifully presented. “When we were young, we were turned out in clothing that she made herself which was always impeccable,” says Carr. “Our dresses had white embroidered Peter Pan collars. And smocking, that was popular. You look at pictures of the royal princesses. We had the same sorts of clothes as they wore.”

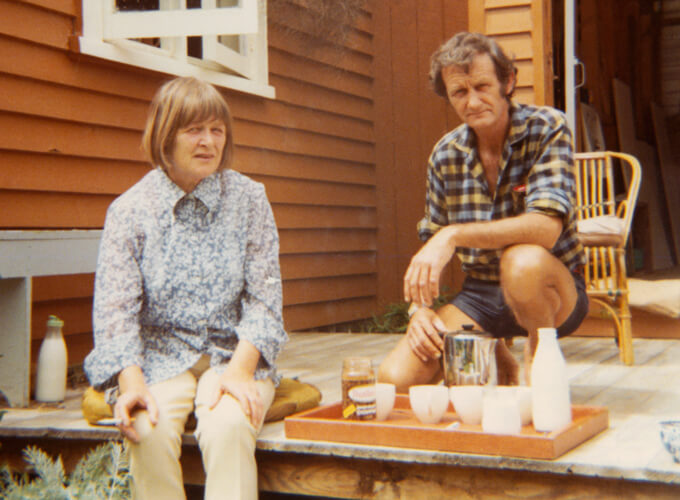

Anne was also kept busy at the Titirangi house, playing host to the creative friends who congregated on the sundeck at the cottage, enjoying “cheap plonk”, that Colin got from West Auckland vineyards. In a picture by photographer Barry Millar, Anne can be seen at the centre of a gathering outside under the trees, her ever-present cigarette in hand, standing between Colin and artists Pat Hanly and Peter Tennant.

Carr says that when people dropped by, Anne would produce goodies in her tiny cooker at the “drop of a hat”. “Suddenly there are tea cakes or scones or pikelets.” Cookery was really another outlet for Anne’s creativity and she was much more adventurous with ingredients than most cooks at the time. Carr remembers a beef stir-fry made with ginger, garlic and herbs. “We all thought that was really lovely and gobbled it up, no sweat,” she says.

Quiet and considered, Anne would keep an eye on the social goings-on from her spot in the kitchen. “She’d come around from her little cubbyhole and stand in the doorway where she could keep her eyes on the pots and things,” says Carr. “Then when something cropped up that she wanted to comment on, she would make a comment. She was certainly there and listening.”

Considered the more intellectual one of the couple, Anne was a discerning critic of Colin’s work and he sought her advice throughout his career. Just how integral and engaged she was to his practice is evident in the journal she kept of the couple’s trip to the United States in 1958. Colin received a grant from the Carnegie Trust for a four-month travel tour to study art museums. The children were dispatched into the care of various friends and relatives around the country and Anne went with him.

She was just as involved in the fact gathering and analysis as he was, recording her observations in tightly packed, even lines in a burgundy, hard-covered exercise book. The journal, which Carr has in her collection, will be exhibited as part of the Te Uru exhibition. When you see it, with its worn spine busting out of its binding and Anne’s fine handwriting spelling out details of the art, people and museums the couple visited on this revolutionary journey, it’s hard not to be struck by the object’s significance.

It was on this trip that Colin and Anne got to immerse themselves in the very latest happenings in the art world. On their return, after seeing the work of abstract expressionists up close, particularly that of Jackson Pollock, Colin moved in an even more abstract direction and started making large-scale paintings to “walk by”.

The diary has never been published. It’s a project that Carr says is on the cards. Many years later, Carr helped Anne to type up parts of the diary and as they worked on it, Anne went back and reviewed some of the text. On one page she has determinedly scribbled out some of her commentary of a particular museum and added the note, “This is Mr Morley’s baby and I must try not to be too nasty.”

While Anne and Colin were overseas, she sent their children postcards and aerogrammes, using different-coloured pens, which she knew they would appreciate. “She knew yellow was my favourite colour so she used gold pen,” says Carr. Despite the long separation from her children, Anne loved her time in the States. “She was very happy then, going on that trip and coming back; she just sparkled,” says Carr.

All through Colin’s career, Anne remained his most important critic.

When the McCahons returned, Colin’s art accelerated stylistically, while Anne’s creative work dwindled. After exploring vast cities and landscapes in the US, the sodden cottage in French Bay lost its appeal. In Colin’s words; “We went home to the bush of Titirangi. It was cold and dripping and shut in — and I had seen deserts and tumbleweed in fences and the Salt Lake Flats, and the Faulkner country with magnolias in bloom, cities — taller by far than kauri trees. My lovely kauris became too much for me. I fled north in memory and painted the Northland panels.”

In 1960, the family left the bush behind and moved to Partridge St in Arch Hill. By now Anne was doing little illustration work. Colin was still working at the gallery but in 1964 left to lecture in painting at Elam School of Fine Arts. Thanks to an inheritance from Anne’s parents, they were able to buy a studio at Muriwai in 1968 and this is where Colin painted through the 1970s until his health deteriorated so much he could no longer make the trip out from town.

All through Colin’s career, Anne remained his most important critic. Their son William, who declined to be interviewed for this story, was quoted in the New Zealand Herald in 2002. “Myself, my mother and [Colin’s close friend] Gordon Brown would talk through issues in his painting which were troubling him, and the final say was always given to her. If she had gone before him, it would have been a devastating blow.”

By the 1980s, Colin was suffering greatly with Korsakov’s psychosis, a condition brought on by excessive alcohol consumption leading to brain damage and memory loss. He had barely any awareness of the significance of his exhibition at the Sydney Biennale in 1984. On what would be Colin’s last public appearance, he became disoriented during a walk through Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden and Anne and curator Alexa Johnston spent the next 24 hours trying to find him. Anne nursed him through those difficult last years. He died in 1987 at the age of 67.

Finn McCahon-Jones, Williams’ son, was a child at the time and has some sense of just how tough it was for the family caring for Colin. “I don’t know what it would have been like for Anne,” says McCahon-Jones. “She was looking after him when he was quite sick for a long time. It must have been really hard. The person that you love, and have lived with your whole life, all of a sudden is somebody else.”

After Colin’s death, Finn and his parents moved in with Anne in her house at Crummer Rd back when Ponsonby could be described as a “sleepy place”. “You didn’t have to look to cross the road,” says McCahon-Jones. “There was one gelato hut and we used to go down to Calabria [restaurant] and get pizzas made. SPQR was a motorcycle fix-it shop that my uncle [Matthew] worked at.”

McCahon-Jones, who is now director at Te Toi Uku: Crown Lynn Museum in New Lynn, has a particular affinity with Anne’s ceramic works, which will feature in the Te Uru show. She started making them in the 1970s after taking classes at Outreach (now called Studio One — Toi Tu) on Ponsonby Rd, and had a kiln in the back garden. McCahon-Jones says he recently spoke to her ceramics teacher, who told him that unlike the rest of the students who were generally at class to chat and muck about, Anne was always very focused.

“This was Anne’s time to work,” says McCahon-Jones. “Colin was really getting old and sick and so this was her place to go.”

What strikes McCahon-Jones about his grandmother’s pots is their 1950s quality, even though they were made decades later. “They’re about form and are well crafted and these kind of beautiful pots that fit into the interior of the house,” he says. “They never seemed out of place with paintings that were painted 40 years earlier, or more. And I always thought they were old. She was a modernist. Colin was a modernist. They were really interested in modernism, so of course when she starts making, she’s thinking about this stuff, so she starts producing these things.”

One of his favourite pieces is a large vessel that sat in the garden under a downpipe catching drips that Anne would use to grow watercress. Later, they realised it wasn’t a vessel at all, but a stool that Anne had made from coils of clay. When it was leather hard, Anne sat in it, leaving her impression in the top. “You sit in it and it’s this very ergonomic, yet organic stool,” says McCahon-Jones. “It’s lovely. There is a real physicality about this stool, which makes you think about Anne making it.”

The physical nature of making ceramics eventually became too much for Anne, and when she could no longer wedge the clay (prepare it by bashing out the air bubbles), she stopped making anything at all.

Anne was 78 when she died in 1993. McCahon-Jones remembers vividly going to visit her in a Mt Eden hospital on her death bed. She was too ill to say anything. She simply wanted to see her grandson, to gather her family near. A Colin McCahon painting of a Nelson landscape hung above her bed.

“She chose that painting,” he says. “It was the only thing in her room. It would have been from before they moved to Auckland — just the sky and the land, cutting the frame in two. In one corner, where the sky and land meet, there’s a little glimpse of colour, whether it’s a sunrise or sunset. Yes, it’s an abstract composition. Yes, it’s a diary entry. But yes, it’s a simple, beautiful landscape from Anne’s past — from those days when Colin and Anne first met.”

Anne Hamblett, promising young artist, may not have picked up a paintbrush after she became Anne McCahon, wife, mother and supporter. She may not have had a long and fruitful career as a painter like her good friend Doris Lusk. But there is no doubt she had a deeply varied creative life, and Linda Tyler may be right: there may have been room for only one artist in the McCahon family, but that artist may never have been able even to exist without Anne. As Carr puts it, “We are all very sure that dad wouldn’t have been able to do what he did unless she had given him her support.”

The exhibition at Te Uru is not an attempt at a big aha moment, some long-last recognition of Anne’s obscured genius. “It’s really to get her out of being trapped because of being his wife and to give her some sort of agency as an individual,” says Tyler. “As somebody who herself would have been perfectly capable of having a sustained career but actually decided to do something else with her life.”

Carr thinks her mother would have been “surprised” about the show. “Some of the paintings have been exhibited before so she would have been pleased to see interest taken in them and happy about that,” she says. “As far as all the other ephemera and other sides of her life, I think she would be very surprised that her journal work and ceramics would have made it into the show.”

The glory works of the Te Uru show may be the paintings Anne did as a professional, but it’s the journal illustrations done on the kitchen table that were so hugely valuable to a struggling family, the journal writings that document such a significant point in her husband’s career and the ceramics that provided solace from nursing an ailing and difficult loved one that when lined up together make the real feminist statement. A woman’s story, untold until now.

“If it paints this picture, then all of a sudden the broader culture is a little richer for it,” says McCahon-Jones. “In one extent, I think every family should do this. I always joke that I’m lucky that I was born into a family [for which] people want to do family research for me.”

A Table of One’s Own: The Creative Life of Anne McCahon, November 19-Feburary 12, Te Uru. www.teuru.org.nz

This article was first published in the November 2016 issue of Metro.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to the weekly e-mail