May 27, 2014 Art

The Kauri Project: Poster Series

The Kauri Project: Poster SeriesLopdell House Gallery

At the Auckland Writers’ Festival recently, African-American writer and activist Alice Walker was hunting for a metaphor. She asked her interviewer, Selina Tusitala Marsh, for the name of a loved local tree. Marsh’s immediate reply was – of course – a kauri tree.

These majestic conifers are ingrained in our psyche as an iconic species of Aotearoa. Slightly slower to enter the national consciousness is kauri dieback, the deadly fungus-like disease that has now killed thousands of kauri, threatens to devastate their remaining population, and is spread easily on the shoes of careless trampers.

Enter The Kauri Project: Poster Series at Lopdell House Gallery, an exhibition to raise awareness about kauri dieback. Five artists were invited to design a poster responding to the kauri’s plight. It sounds serious, and it is. Yet each of the five posters created for this project is a work of poetry.

Photographer Natalie Robertson transforms the tree’s familiar mottled bark – earthy grey-brown patchwork, blooming pale lichen – into a cloudy backdrop. Against it, the long shadow of a lone kauri casts a pall of mortality over the raw life of the bark, though its branches still reach skywards.

Philip Kelly zeroes in on the tree’s distinctive rust-colored fallen leaves, and something about their close, glistening dew has me smelling a peculiar bush dankness I had been forgetting. The Maori word ‘IHI’ punctures the image in a tall slender lettering like kauris in their prime, denoting the trees’ life-force.

In Haru Sameshima’s black-and-white photograph a kauri-studded patch of bush appears ghostly, melancholy, otherworldly. Before this forest chamber I relive my own encounters with the patupaiarehe/tree folk at Waipoua, and with the 2500-year-old tree Te Matua Ngahere in all his gravitas. The central tree’s radiating force is unembellished here by any text.

In her whimsical hand-drawn image, Charlotte Graham pictures the kauri-force in cross-section, concentric trunk rings circling outward through the years. A protective assembly of native birds hovers around in little booties, reminding us to mind our shoes. The kauri is essential to their ecosystem, but now they become kaitiaki/guardians in turn, calling ‘tiakina i te whenua, kia whakatika ra’ – ‘protect the land, correct it now’.

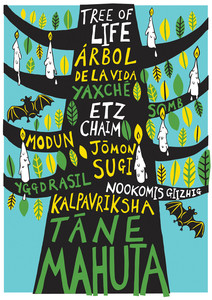

Finally, Tessa Laird’s bold graphic poster depicts a towering black tree emblazoned with names for the tree-of-life from various world cosmologies. Tane Mahuta takes pride of place as both the Maori forest god who separated Rangi and Papa and ushered in Te Ao Marama (the world of light) and the name of our largest still-growing kauri tree. Her tree combines a 1960s psychedelic strain of hopeful protest with a reminder of trees’ necessity for life everywhere on earth.

Like the kauri seed, these posters are small but mighty, harnessing the spirit of this magnificent tree with reverence and gratitude. They are a fine example of art intersecting with activism, awakening our hearts to care the next time we read or hear about dieback.

And like the kauri seed these posters can be reproduced and disseminated far and wide. They are plastered on the scaffolding wall of Lopdell House (undergoing refurbishment) in Titirangi, and gallery visitors (at the temporary New Lynn site) get one to take home free. Here’s hoping our collective bill-posting works virally to counter the contagion of the fungus itself. And here’s trusting in that fervent optimism that envisages kauri standing tall, as text on Robertson’s poster suggests, ‘ki uta, ki tai’ – from the mountains to the sea once more.

Until June 9

lopdell.org.nz

Image: Kauri Project poster by Tessa Laird, courtesy Lopdell House Gallery and the Chartwell Trust.