May 4, 2015 Art city

In Manassas, Virginia, a 126,000 sq ft building houses one of the world’s largest collections of genetic material. Among the American Type Culture Collection’s (ATCC) 3400 cell lines, 18,000 bacteria strains, 2000 animal viruses and eight million cloned genes — all stored alive, ready to be deployed in the wars against illness, ageing and disease — are a handful of living cells, constantly multiplying, from New Zealand. They belong to the artist Billy Apple.

For more than 50 years, Apple has been one of the major practitioners of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, using everything from bronze editions and photography to Xeroxes and printed receipts. Now, biotechnology presents him with the very real possibility that he could reproduce himself. All it would take is for one zealous collector to decide he wanted his own infinitely reproduceable line of Billy Apples — and the artist, as one of his recent canvases declared, will live forever.

Immortality. It feels like the perfect not-end to a career that started on a cold London day in 1962, with the disappearance of a 26-year-old New Zealander called Barrie Bates.

—

Billy Apple’s art can be hard to like. All those apples, the obsession (or what can seem like obsession) with his own name, which he chose. The work is so reductive, many people think he’s just making fun of them.

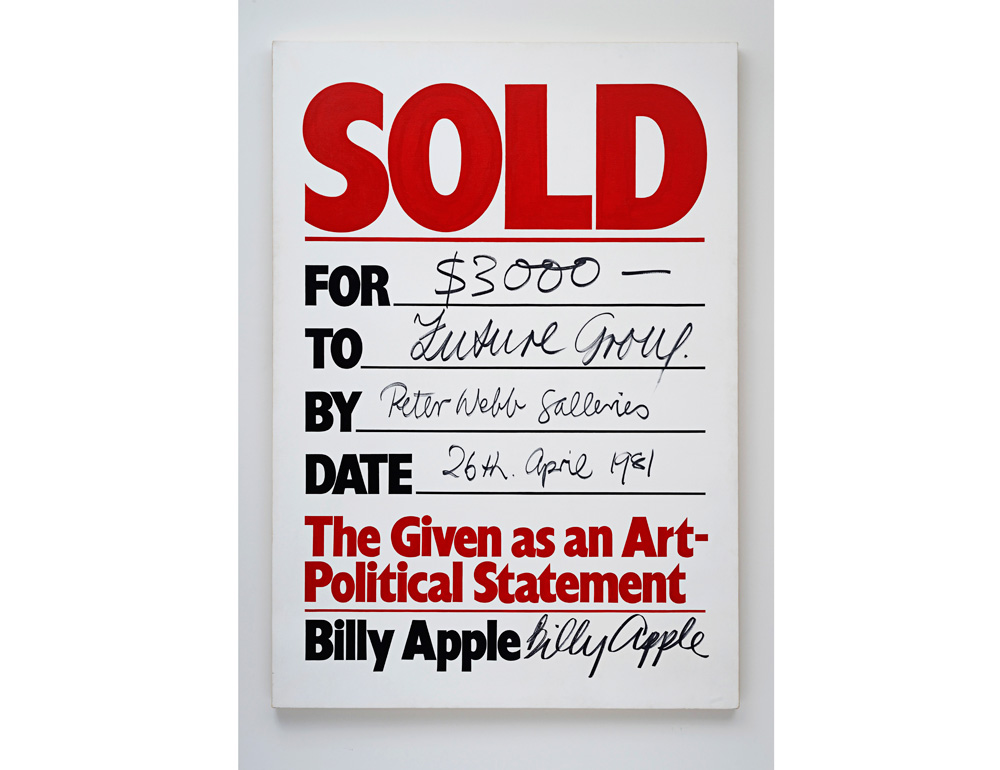

In the From the Collection series, canvases simply state their title with the addition of the owners’ names. Even his legal bills are art: the law firm Minter Ellison Rudd Watts has canvases in its offices stating the amount of credit extended to Apple over recent years. It’s a lot: the process of becoming a registered trademark has clearly been a long, expensive and litigious one.

“The full account is on the wall,” is how Apple explains it, sitting in his Mt Eden home. “It becomes a work about intellectual property.”

That IP now extends to Billy Apple coffee and Billy Apple cider. “Granny Smith and Fuji,” he says enthusiastically. “It’s gold-medal stuff.”

He gives me a cup of the coffee. The next thing he and his longtime partner Mary Morrison give me is a frenetic rundown of everything he’s working on. I can’t keep up. When Morrison sends a list later, there are more than 20 projects on it. Apple is 80 this year, and working with urgency. “Being an artist is a 24-hour job,” he says.

The house they share is like a live-in version of the list: boxes of files everywhere; correspondence still to be dealt with; floor plans of various galleries; bubble-wrapped artworks leaning against walls. She’s an ex-critical-care nurse and artist, who looked after him following a hernia operation in 1998. They’ve been inseparable ever since and she is now the brand ambassador, and a kind of gatekeeper.

Apple is wary of journalists. He doesn’t like being asked if what he does is actually art and he can’t stand the fruit puns. He once told me off for describing something as being “at the core of his practice”. I didn’t even realise what I’d said.

The brand is the artist, which is where things start to get complicated. “To understand the art, you have to understand the man,” Morrison says. “You have to understand that it’s personality driven. And Billy doesn’t have an average persona. People say his work’s simple, but it’s not. It’s pared back, and pared back, and pared back until he can cut away no more. That’s when he’s got to the purity of the point.”

He works with gold; he loves Grand Prix motorbikes; he gets other people to pay his bills; he doesn’t make anything himself but gets collaborators to do all that for him. And now the Auckland Art Gallery (AAG) has opened a massive retrospective, called Billy Apple: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else.

The show’s curator, Wellington-based art historian Christina Barton, describes it as “an extended self-portrait, of a man and an entity called ‘Billy Apple’ negotiating and interrogating his relationships both with himself and with the world around him”.

With around 200 works, this is the largest solo exhibition the AAG has presented in years. Billy Apple is now officially one of our greatest artists.

—

In 1959, Barrie Bates, a young graphic designer, left New Zealand to take up a place at the Royal College of Art in London. Once there, he found himself part of a remarkable student intake; among his classmates were David Hockney, Derek Boshier, Allen Jones, RB Kitaj and Pauline Boty. Collectively, they would go on to spearhead the emergence of British Pop art.

Bates and Hockney became particularly close. They were mirrors of each other: Hockney the boy from Bradford; Bates the lad from the colonies. Together at the poshest art school of them all. One gay, the other straight. And both ferociously determined.

“Both of us wanted to work hard,” Apple says. “Not just fuck off to the pub. We’d often work at night-time. We’d hide out and they’d shut the place down, and when things were quiet, we’d come out and go into the print department, or we’d go to the supply place, climb the wall and steal a roll of canvas. Whatever had to be done.”

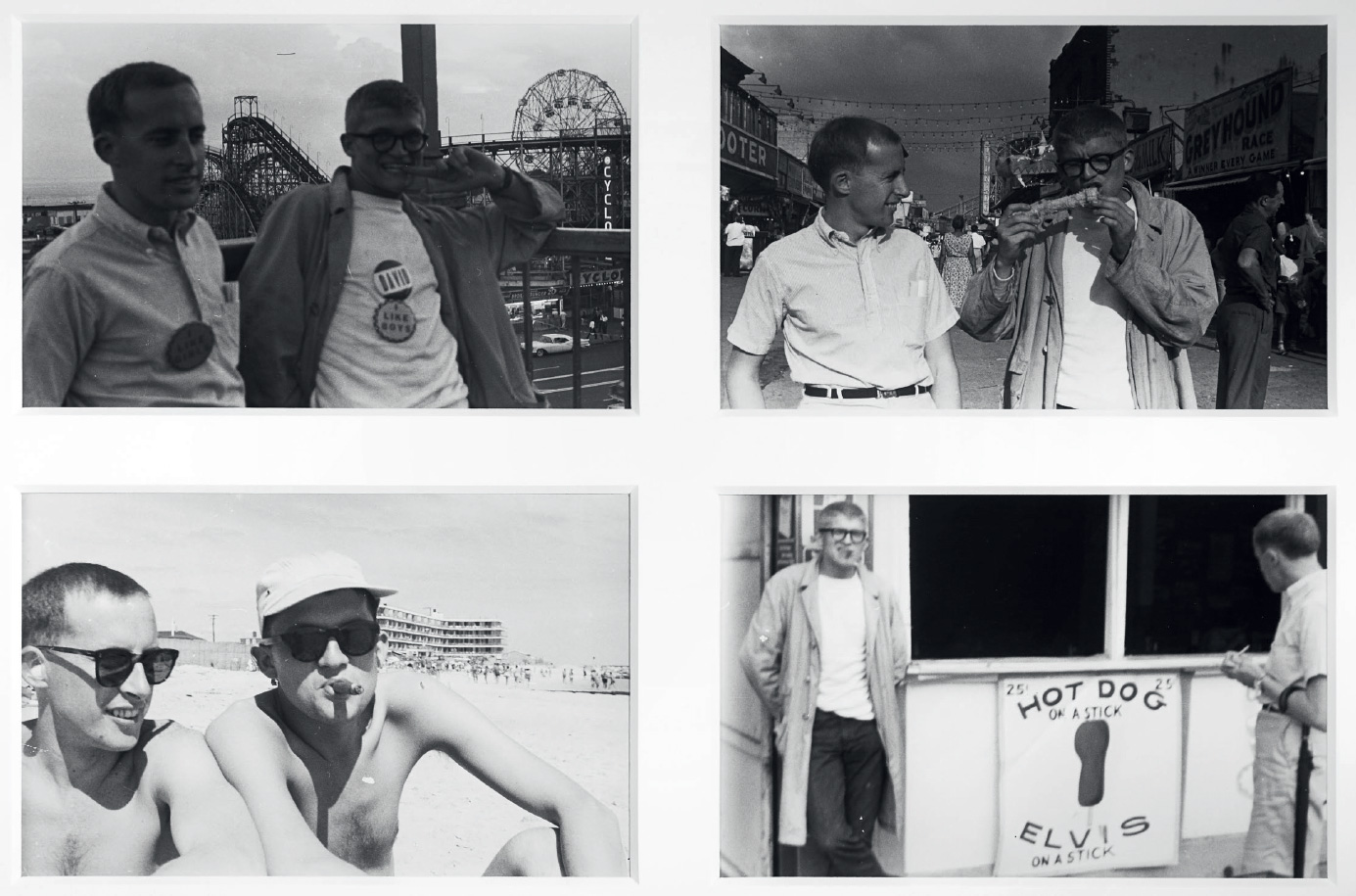

At Apple’s home, we look through a pile of photographs of Bates and Hockney. There are several of them together at a fairground. It’s the summer of 1961. The pair had travelled to New York on a student charter flight, and though they stayed in the city separately, they met regularly — including, as the photographs show, at Coney Island.

I look at four images from the day, arranged in a grid. Bates and Hockney wear badges: Bates’ says “I Like Girls”, Hockney’s “I Like Boys”. Hockney hams it up for the camera, munching on a corncob, sucking a cigar. In one, they’re shirtless on the beach.

Surely, I ask, the pair knew exactly what they were doing: walking around a tough New York neighbourhood with Hockney openly declaring his homosexuality, brandishing anything phallic he could find. They were asking for trouble.

Apple shrugs. “We didn’t think about it. The buttons just declared what we liked. We met up, sat on the beach. It was a day out.”

Come on, I say. Apple pauses. Then the conversation takes a turn.

Mary Morrison says, “I read Bates’ Royal College dissertation, and his manifesto. I got to the end of the manifesto, and it seemed really sexually ambivalent. I said to Billy, ‘Were you bisexual?’ Then I waited for a minute and thought, ‘No, you’re too scared to be bisexual.’”

She and I laugh. Apple grins, just. “So I asked him who wrote them.”

“Ann Quin,” Apple says. “She was a good writer.”

A good writer. Quin was one of the major experimental novelists in 60s Britain. It turns out that in 1962, she was also a secretary in the Painting School at the Royal College. And she was sleeping with Bates.

“We had a relationship. She researched and wrote my thesis for me. As a conversation between Vincent van Gogh and [the proto-Pop American artist] Larry Rivers at the Five Spot Jazz Club. It was called Pop Corn. In those days, they handed out topics for people’s dissertations. If you’re in the Graphic Design School, they give you van Gogh, because they think you’re a bit fucking stupid.

So I did it the way I’d do any business. You get the best writer around and away you go. She ghosted the whole bloody thing. But boy, did she piece it together.”

Bates and Quin were together for about six months. “She was a pretty wild person,” Apple says. “If she wanted a pee, she’d just stop in the middle of Kensington and go between two cars. She was uninhibited like that. But she really was a very good writer.” Just over a decade later, Quin brought her own story to a terrible end. “You know that classic Reggie Perrin series, where he walks into the water?” Apple asks. “She did the same thing at Brighton Beach. And never came out.”

After the US trip, Bates and Hockney stayed tight. Despite being rising stars, the college threatened to fail them both, essentially because they refused to do their homework. Bates, in fact, assumed he had failed and left school completely.

Given the hot dogs, the cigars, Quin’s lack of inhibition and talk of Bates’s orientation, I ask the obvious question about his friendship with Hockney. But no, it never became sexual. Even if it had, what seems more important is that Bates, a colonial outsider, was being drawn into complex London relationships with other people from the edges: Hockney the northerner, who was openly gay; Quin, who was clearly “different” too. Bates was trying to find his own reflection.

Around this time, he also took a strange trip into Tito’s Yugoslavia. His mother was a Croatian New Zealander, and he travelled to connect with her relatives — not at her request, but under his own steam. Once there, he felt the relatives were passing him on quickly: from Rijeka to Zagreb, then Sarajevo and finally Split. Either they were afraid Communist informants would see them associating with a Brit, or they just didn’t want him there.

I’ve never heard Apple talk about the trip before. He leaves us for a second, and comes back with a file. Inside it is every passport he’s ever had. He picks out the oldest one, and starts turning the pages. With a magnifying glass, he scans for the Yugoslavian stamps: “Here they are,” he says. “16 to 22 April, 1962.”

It was the last meaningful attempt Bates made to connect with his familial past. Seven months later, to the day, he would cease to exist.

—

On 22 November, 1962, Bates’ search for an identity ended for good. In the London flat of his friend Richard Smith, he bleached his hair and eyebrows with Lady Clairol Instant Crème Whip and disappeared forever.

In his place stood Billy Apple, a living, breathing “brand”. It happened in a flash and it was one of the most radical moments in 1960s art; up there with Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, and Dan Flavin making sculptures from fluorescent tubes, and Richard Serra filming himself trying to catch lead.

Pop art was about breaking down the line between art and life, but the emergence of Apple was of an entirely different order. It was the difference between illustrating that dissolution and actually becoming it — and not just being it temporarily, but living with the decision for good.

Morrison describes that moment of transformation as “a psychic severance”. Bates wiped himself off the human map, cutting his ties with everyone and everything. For a long time, even his relatives back home had no idea where he’d gone. He didn’t return to New Zealand until 1975, and then only for a short visit.

Ask him about the name change, and he’ll tell you exactly what he wore in his first days as Apple: natural-coloured Levis, white Keds, a white Burberry trenchcoat. But it’s extraordinarily hard to draw him on its psychological impact.

“I could have just done a show called ‘Billy Apple — End of Story’ [and gone back to being Bates],” he says. “But there was no turning back. It was a fresh start. I hadn’t seen my family since 1959, and nobody made long-distance calls in those days. They had the Metropolitan Police looking for me in 1963. The cops came around to find where I was, to make sure I was still alive or whatever.”

Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of the Serpentine Galleries in London and widely regarded as the art world’s most powerful person, has long been interested in Apple’s work. “Obrist wanted to talk to me about epiphanies,” Apple says. “I told him the name change was the epiphany. But how many more do you want me to have?”

He laughed, but continued more seriously. “You don’t want too many epiphanies. They get in the way. There was only one. After that, everything went towards supporting it.”

What Billy Apple did, once he became Billy Apple, elevated the man from a good artist to a great one. He recognised that his job from that point on wasn’t to impose his inner life on the outer world. After all, he no longer had a personal history to draw upon. It was to show how the outer world imposed itself on him.

While most of his contemporaries back in New Zealand were bemoaning the tyranny of distance, he was unpacking the full force of two interconnected burdens — the self, and the body — in an age when technology and consumer comforts promised to release us from the limitations of both.

I’ve known Billy Apple for more than 10 years. In 2002, as a recent art history graduate living in Hamilton, I wrote about his work Severe Tropical Storm 9301 Irma, which arose from a freighter journey he’d taken from New Zealand to Osaka in 1993, when the ship narrowly missed being engulfed in a tropical storm. Apple took nautical and meteorological data from that and turned it into an installation, with a soundtrack by the composer Jonathan Besser.

It had all the hallmarks of his best works: technical precision, talented collaborators, reducing lived experience to pure information. But underpinning it, it seemed to me, was something else: raw, human fear. For all its programmatic attention to the data, this was a work about a man confronting the possibility he might never make it back to port. It was, I thought, as potent a response to nature’s power as Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa.

A couple of weeks after the article was published, my phone rang. I choked when I heard the voice on the other end, and waited for the full treatment; I’d heard how prickly he could be. But Apple had liked what I wrote. He wanted to work together on something.

So, we decided to restage a work he’d originally made in New York in 1969, called Four Spotlights, at Hamilton’s Ramp Gallery. That’s exactly what it was — four of the gallery’s spotlights, mounted on tracks in a perfect square, pointing straight down at the floor. The rest of the gallery was completely empty.

Not long before it was due to open, I picked him up from the railway station and took him to the gallery. He’d given me clear instructions before he arrived — the space needed to be spotless — and my intern and I had polished the floor and repainted the gallery, twice.

“What’s that?” he said, pointing to a paint-drip. “And this?” Some of the things he pointed out, no one else would have ever noticed. But, at 24 and keen to work with him, I conceded the point. I took him to his hotel, went back, and we started again.

With Apple, nothing — especially people’s feelings — is allowed to get in the way of the idea’s purity.

—

Pedantic, reductive and difficult, Billy Apple was on a collision course with his contemporaries in New Zealand. The most famous example is his showdown with Pat Hanly. In 1982, Apple turned a room in the Herne Bay home of Francis Pound and Sue Crockford into a pristine gallery space. At the launch, Hanly took to it with splashy paint. Apple was furious. Still is.

“I just walked out,” he says. “After that, whenever I saw Pat, I’d remind him that I still owed him one. It was head-on versus hands-on, if you want to look at it like that. I’ve certainly never been hands-on, not like them.” He means Hanly, but also other painters of his generation, like Don Binney. “They were making old men’s art. The issues they were looking at were well and truly closed. Finished. We’d moved things on. Way on.”

He might be difficult, but people keep working with him, and following his work. I’ve chased him around the world, to London and the Netherlands, to New York and Detroit. Barton has dedicated a huge chunk of her professional life to his work. The writer Wystan Curnow has collaborated with him for more than four decades. Many of our best curators have cut their teeth on Apple projects.

Then there are the collaborators: the Minter Ellison Rudd Watts partners, Saatchi executives, apple breeders, coffee blenders, mechanics, scientists and signwriters. “It’s always been how I’ve worked,” he says. “If you project-manage the thing, and you know how to talk to people, you get the best out of them. You’ve got to bring people into the project, so they’re part of it.”

His influence on younger New Zealand artists is profound. Despite his age, he’s out most weeknights at exhibition openings, finding out who the new talents are. And if he rates them, he’ll work with them, even if they’re straight out of art school and showing in ragged artist-run spaces.

In the larger scheme of things, his uncompromising conceptualism, overseas achievements and longtime expatriate status have provided a kind of road map for international success, for local artists from Julian Dashper to Simon Denny.

Contemporary art in this country wouldn’t be what it is without him, so why isn’t he more widely appreciated here?

Barton provides one explanation: “He’s not a New Zealand artist per se. He never suffered from the ‘provincialism problem’ and his work has always refused to conform to nationalist discourses. That’s one of the reasons it speaks so strongly to younger artists.”

Morrison has another perspective, on both his importance and his neglect: “They’re realising Billy got there before everybody else. He was always a step ahead. But that was the problem: he was a step ahead.”

—

After becoming Billy Apple in London, he moved to New York in 1964 and was included, that year, alongside Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns and other young luminaries in American Supermarket, a seminal Pop exhibition that took the form of a shop (Warhol’s Brillo Boxes and Apple’s bronze fruit for sale, and so on).

He was one of the first artists to use neon. But by the time that was taking off, he’d moved on, befriending a scientist doing government research into lasers (the pair once shot a laser at the moon, just to see if they could hit it from Manhattan). And when other Pop artists were playing with silkscreens, Apple was working with a company called Xerox, running off his work using a new reproduction technique the corporation thought might have legs.

In 1969, he changed tack. Instead of continuing to make objects, he opened one of New York’s first experimental art spaces, and became a leading figure in conceptual art, recording the banalities of daily life — cleaning spots of dirty windows, picking up broken glass, even documenting his own bodily functions.

Around this time, he also started to think about how he could intervene directly in museums and galleries, well before the art world had labelled such work “institutional critique”. The Transactions — oversize receipts recording the details of their exchange — were an extension of this, examining the relationship between the art market’s backroom machinations and the artist’s very real financial need “to live like everybody else”.

Apple kept anticipating, and as Morrison says he never stood still long enough for art history to catch up with him. American Supermarket was and still is regarded by many commentators as one of the starting points of American Pop. For Apple, “it was the conclusion of it, really. I mean, where do you go after that? It was the end of the game. It was a collective moment, but that was it

Many of his contemporaries from that show — Warhol, Lichtenstein, Johns — went on to superstardom. He didn’t. “That hurt a bit. I used to get very envious. I learned to not be jealous though. It used to fucking hurt when The Whitney [Museum of American Art] wouldn’t consider my projects. The best thing I ever did was open my space at West 23rd Street. There was no one to ask. You could just get on with things.”

Suddenly, though, things are changing. The AAG retrospective reflects the serious attention Apple is now getting overseas. This month he’ll be in an exhibition of international Pop art at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis — one of America’s most important contemporary institutions. His London dealer, the Mayor Gallery, has been selling work to the National Galleries of Scotland and Tate Britain, while his Auckland dealer, Starkwhite, is making significant inroads in Asia.

In 2009, one of the world’s most influential curators, Nicolaus Schafhausen, gave him a big survey show in Rotterdam, and Obrist is also circling. And in 2012, Europe’s most important art magazine, frieze, published my in-depth interview with him. The world cares about Apple now in a way it hasn’t since the early 60s.

“We’re really obsessed with this machine, our body. And the machine creates the illusion of consciousness, of a soul and a self, all that stuff. So what happens if you take a bit of it out and give it away?” It’s not Billy Apple speaking but Craig Hilton, a geneticist who lives on Waiheke and teaches at Unitec.

Hilton is also the man behind The Immortalisation of Billy Apple®. Getting Apple’s immortalised cells into ATCC’s collection was just Hilton’s first step. Since then he has also had Apple’s DNA sequenced, a process that gives a full picture of his vulnerabilities — the little flaws, tics and hereditary trapdoors that leave him open to certain illnesses and diseases. A map, in other words, of the most likely ways Apple will die.

This is more than an art-world gimmick; it’s real science. Apple’s cells are being used for research.

Hilton’s credentials are world class. After a PhD from Otago University, he worked at Harvard Medical School. He’s also an artist, with a Master of Fine Arts from Auckland University.

“I’d like art to do something that science hasn’t done, or maybe doesn’t have the nerve to do,” he explains. “And when I was thinking about a project that would have both real art and science value, Billy’s practice fit perfectly. Normally, for ethics approval, you have to make sure the people are anonymous. But the whole point is that it’s Billy; they’re called Billy Apple® cells. So Billy signing away his privacy was a kind of ethical backdoor.”

Apple agreed to be part of the project almost immediately. His freely available cells, and his medical information, are biological byproducts of the WebMD age. We live in an internet culture of paranoid self-diagnosis, and yet few of us really want to know if we’re going to get Parkinson’s or early-onset Alzheimer’s. Then there’s the moral conundrum of what this does for our children: do we really want them to grow up knowing all the hereditary horrors woven into their genes?

And, of course, there is the biggest ethical vortex of them all: the fact that one day we could be cloned, without our permission, because we’ll already be dust.

It’s the most complex and radical project Apple has been involved in since the name change. It’s also how the brand will outlast the body. “Making the cells and the DNA sequencing available to everybody and anybody means they’re effectively open-sourced,” Hilton says, “which is what a lot of brands now do, not charging for their products — Google, Facebook and the rest.”

Hilton also makes the point that, as DNA sequencing becomes cheaper, big companies — especially life and medical insurers — are going to mine our genetic information for risks in much the same way they currently use our online activity to direct their marketing. “We’re all going to be in this situation soon. But Billy’s doing it now. He’s stepping into the future.”

—

It’s the first Monday in March, the first day of install, and the AAG’s young curator, Stephen Cleland, is showing me through the rooms.

Half are freshly painted; the others are still building sites. A few works lean against the walls and there’s also a special incubator, along with a giant CO2 bottle to run it. By the time the show opens, the incubator will contain Apple’s living cells.

The artist is leaning over a worktable with the exhibition designer, looking at floor plans. They’re discussing sight lines. “The long views are very important on this thing,” he says. Even though each room deals with a separate theme, he is crystal-clear about how he wants viewers to move between them, to see connections.

He’s even more adamant about the standards he expects. As we move through the unfinished rooms, he points out patches that need more sanding, electrical plates to be moved, slight bows in newly built walls that must be straightened before anything can be hung. Everyone there sucks it up. Everyone there is at least 40 years younger than him.

Over the coming days, as the works are brought up from storage, the sight lines start to tell the story. Apple’s neon signature. The self-portraits, in which Apple’s image progressively disappears. The bronze apples. Photographs of his laser installations. Xeroxes. Documentation of his cleaning works and alterations to museums. His golden apple. An entire room of From the Collection pieces. Racing cars and motorbikes, each accompanied by its own special canvas.

Taken in isolation, each work could seem cold, stark, ungenerous even. Together, I’m surprised at how beautiful and poignant they are: the neon signature that asserts his existence in blazing red light; the From the Collection works, which feel more like a record of relationships than of pecuniary exchanges.

The tiny gold apple, which is simultaneously a glorious, delicate thing and a suggestive portrait of deregulated Auckland. And, of course, his cells multiplying in their incubator, embodiments both of him and of our absurd desire to defeat nature. A cumulative account of a life lived publicly, held up as a mirror to our technological, physical and consumerist obsessions over the past 50 years.

Barton says she is still surprised by the depth of the continuing “self”-examination, and what it reveals. “As much as there’s an evacuation of personality in the production of a ‘brand’, there’s also something else — something which might almost have a tragic cast: the search for perfection, or a system on which to order one’s life, the disappearance of a ‘subject’ and how that affects all his work.”

At each end of the exhibition, she’s positioned a modest photograph. At the start, a young man with newly blonded hair sees himself for the very first time in a small handheld mirror. It’s not a good photo, shot from a low angle so that an overhead lamp blows the light out and gives him a blurry, auratic glow. At the end, a man in his seventies peers through a microscope. He’s looking at his own cells, just extracted, splitting and renewing, destined to go out into the world to find new homes, new hosts.

Parentheses for a story that refuses to end.

In my last meeting with him, Apple tells me about one of his earliest visual memories. As a young boy, he visits his Croatian grandparents in Mt Albert. It’s sometime in the mid-40s. They give him a jigsaw to complete — sent, Apple assumes, from relatives in Yugoslavia. As the pieces come together, a gathering of young, hopeful people emerges. Many are wearing tan uniforms. There are flags and banners everywhere: black, white, red. It is terrible. It is his first remembered encounter with graphic design; the 20th-century’s most defining and horrific exercise in cultural branding.

On the night Apple’s show opens, white banners surround the AAG, fluttering in the March breeze. On them a single, bold, black logo.

“I’m becoming quietly excited about it now,” Apple tells me. “It’s a bit like getting one’s affairs in order. Even though ‘Billy Apple’ the brand is 52 years of age, I’m living in a 79-year-old body, and it’s hard. The mind’s quicker than the body. But the comforting thing is that, with the cells out there, there really isn’t an end for me. There’s no final date. Can you name any other artist in the world who’s done that? Nobody.”

—

This story first appeared in the April 2015 issue of Metro.