Oct 13, 2016 Art

Above: Space Work 7 by Judy Millar.

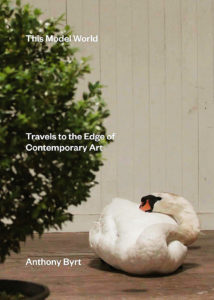

This Model World: Travels to the Edge of Contemporary Art

Anthony Byrt

(Auckland University Press, $45)

Metro art critic Anthony Byrt has published his first book.

This article is published in the October 2016 issue of Metro. Photo by Shaun Waugh (and supplied).

When the artist Judy Millar declared, on stage at the Going West Books and Writers Festival last month, that there is no canon and art history is dead, Anthony Byrt, sitting right next to her, looked decidedly uncomfortable.

It was a session to promote his book This Model World. Millar, who looks uncannily like she might be the actor Bill Nighy’s sister and is a good friend of Byrt, appeared to believe she was explaining his view of art.

She wasn’t. Byrt responded with a reference to journalism being the first rough draft of history. He was, he said, doing something like that for art criticism.

Indeed he is. This Model World sets down a series of markers: here in this space at this time, there are these things happening, and they seem like they are significant, and this is my attempt to explain why.

I know. The qualifiers abound. Only a fool would be definitive about art. Only a fool, you might think, would want to be an art critic. There you are, bouncing from the academic absurdities of the art schools to the machinations of the dealers, trying to find sensible things to say for the benefit of collectors, curators, the other art media, the general media and, by the way, the artists, and, by the way, the public too.

And — as Judy Millar may have been insinuating — is there really anything to say? Whatever you think art is, somewhere in your definition you have to allow that it exists beyond the reach of explanation. Art does a job that prose can’t do. In the end, it defies us.

The job of the critic is to push out the end. To delay the point where the work just is, while you do your best to provide us with a richer, subtler appreciation of its qualities. Step forward, Anthony Byrt.

BYRT WON THE Canon Reviewer of the Year award last year, writing for Metro. I was his editor and I was thrilled about that — and I’m not disguising my partisanship here. But it doesn’t follow that we see eye to eye.

When he told me he wanted to write a feature on Billy Apple, I said okay, but I want you to know I don’t get Billy Apple at all, so you have to persuade me I’m wrong. The wrestling began.

He drafted, I critiqued, he rewrote, I critiqued again. One Saturday morning in a cafe, we had a very long, very intense session deconstructing his story.

He believes Billy Apple is a genius, I think. He’s also a disciple, having once been a studio assistant for the artist, and in all the essays in this book he is, to varying degrees, embedded.

He uses the word himself, referring to his willingness to get alongside an artist, sometimes but not always to become friends, to spend enough time with them to understand not just the work but the person making it.

He uses the word himself, referring to his willingness to get alongside an artist, sometimes but not always to become friends, to spend enough time with them to understand not just the work but the person making it.

For the reader, it’s a rewarding process. Byrt sees things and describes them clearly. He has a very good eye for the telling moment and is good with revealing metaphors, too. He lets the artists speak but he does not, on the whole, allow his admiration to overwhelm his judgment.

He wields the intellectual’s hesitant, speculative, conditional analysis with enough confidence to explain himself but not with so much that he tries to have the last word. He loves his art and he wants to share.

Byrt’s focus is largely on artists at the top of their game, especially those who have been in contention for the Walters Prize — our pre-eminent award for contemporary art. He doesn’t always agree with the choices of various judges, but he does occupy a mainstream position in that world.

Apple and Millar get their own chapters, as do Simon Denny, Yvonne Todd, Shane Cotton and Peter Robinson. Specific works by half a dozen other artists get shorter essays, including two shoots that stretch far out by Shannon Te Ao, which was shortlisted for this year’s Walters Prize.

In the modern manner, the book mixes the personal and the professional: Byrt’s family situation, travel experiences and encounters with the artists provide the flavour of a memoir, but his larger purpose in telling these personal stories is to provide context for his experience of the art.

The personal also gives us an easy way in. Artists’ studios are his happy place, he says, and his warm, writerly enthusiasm makes it easy for us to join him there.

THE CHAPTER ON Billy Apple is similar to the magazine feature except it’s more the way Byrt wanted it. He says he thinks people have trouble with Apple because the artist is an excellent reductionist and we’re not sure what to do with what’s left. Also, that he works across disciplinary boundaries and that causes conceptual problems.

Mmm. Not really. Sceptics would say that Billy Apple worked out how to monetise his life, which is fine, and talked us into fetishising his hobbies, which is disappointing, but none of it explains why we have to treat him as an artist. Or, at least, a good artist. Why do we have to care?

You can tell I’m still not convinced. But that’s not really the point. I’ve learned more about Billy Apple from Anthony Byrt, and been glad to learn it, than I ever would have without him.

We went through a similar process when he set out to write for Metro on Simon Denny, on the occasion of Denny’s installations at the Venice Biennale. Byrt thinks Denny is possibly our greatest living artist, although he knows the term is fraught.

Partly it’s because Denny has a higher standing in the international art market than any other contender, alive or dead. But mainly, I think, it’s because of the zeitgeist. Byrt asks, is Denny a critic of the corporate world or an integral part of it? He says Denny adopts a “strategic ambivalence” towards his role, which means the answer is both. That renders the question a little facile but also signifies the artist has a bravura skill.

All those impossible-to-answer questions about aesthetics, money, cultural relationships and art history. How can an artist be original? What is art if it’s controlled by a market? What should an artist even do?

It’s the stuff of rabbit holes and Mad Hatters, and Denny’s work straddles it with complexity and grandeur. You might run out of words but you still feel there’s something massively important sitting there. Byrt certainly does, and he grapples almost ferociously with its meaning.

Only a fool would be definitive about art. Only a fool, you might think, would want to be an art critic.

Denny’s work at Venice was about the Five Eyes surveillance network: the mechanics, the politics, the cultural impact, the imaginative threads it unravels. He wasn’t trying to analyse Five Eyes or explain it to us, or even to have a view on it. He’s not a political polemicist.

But he may be an aesthetic one. The work was enormous, site-specific in two locations and, on the whole, pretty ugly. It raised questions about how power is wielded, about what aesthetic values are and about how they might be important to art.

It didn’t search for answers. Denny doesn’t want us to understand his subject, says Byrt, but he does ask us to look, because the work is worth looking at, for what you will see and for what it might do to you. And that’s the same as it ever was: an artist asking us to just look.

Much as the chapters on Denny and Apple are important in this book, they’re not quite as good as those on Yvonne Todd and Shane Cotton. When Byrt writes about artists he reveres — Peter Robinson is another one — a bit of smoke gets in his eyes.

But he hasn’t always been as convinced about Todd and still isn’t about Cotton, and his doubts force him to use plainer language and work out more clearly what he really thinks. And in the case of Todd, he came to like her work in spite of himself, rather than appreciating it through the mediating construct of cultural references or art theory.

Then there’s Judy Millar. Byrt is neither troubled by her nor in awe. He just really likes her work and he’s good at explaining why. That’s the beauty of this book: he never forgets that the reason he takes us down the rabbit holes of contemporary art is to share the stimulation and delights he has found there.