Mar 16, 2022 Art

When Australian curator Natalie King first approached Yuki Kihara to propose a project for the New Zealand pavilion at the 2022 Biennale di Venezia (Venice Biennale), Kihara declined.

The biennale is the world’s premier art exhibition. Founded in 1895, it draws more than 600,000 visitors from all around the globe to the sinking city to see the cream of the art world’s crop. But after two previous knock-backs, Kihara felt that “maybe Venice Biennale is not supposed to be for somebody like me”, she tells me. I’m startled by the vulnerability Kihara is expressing and her resignation that this prestigious international art event might not be for her, though she is an artist known for ferocity, determination and ambition. It’s the last part of her sentence that stings — like me.

Of Sāmoan and Japanese heritage, Kihara is an interdisciplinary artist who boasts a long list of previous exhibitions in some of the world’s most significant galleries and museums. In 2020 she was named one of the Arts Foundation Laureates, winning the My Art Visual Arts Award. It would seem that someone like Kihara is on the perfect career trajectory to go to Venice, a sentiment shared by the pleased community rumblings when her unanimous selection was announced in 2019. “Timing is very important with Venice,” King tells me, and clearly this is Kihara’s time.

For the biennale, Kihara will present Paradise Camp, an exhibition that brings with it a lot of firsts for New Zealand — she will be the first Pacific representative, the first Asian representative, and also the first fa’afafine (Sāmoa’s third gender). Suddenly, we see what the words like me point to. Being the first — and in this case also the only — representative of multiple communities comes with great responsibility and an immense weight. The artist acknowledges this particular tension when she tells me she feels as if she is the tip of a dagger that is being repeatedly used to pierce through a surface to cut new openings. Kihara admits that just being in her position “can help to widen the door for many of us who have been excluded from this very, very privileged world”. But, at the same time, “I know that if I fuck up, they will shut the door on us immediately.”

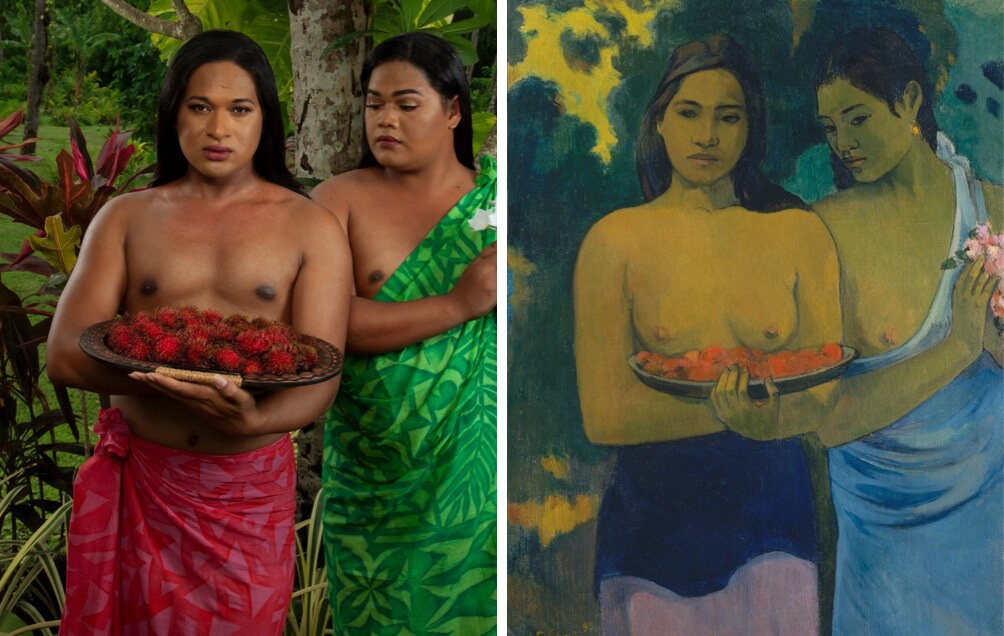

While many of the details of Paradise Camp are embargoed until it opens in April, we do have one clear signpost of what’s to come. “The hero image, the two fa’afafine, is based on Gauguin’s painting of the two Tahitians [Two Tahitian Women]. I call it upcycling. In the context of sustainability, upcycling means that you take something original to improve it. And that’s what I’m doing.”

Left: Yuki Kihara, promotional image for Paradise Camp, 2021. Right: Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women, 1899

I’ve often wondered about Kihara’s continued inquiry into Paul Gauguin, an artist heavily criticised for his hyper-sexualised depictions of Tahitian women. But it’s clear in talking to her that Gauguin’s work, if considered through a particular lens, has many more layers to it.

In 2008, Kihara had a solo exhibition called Living Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Met is an incredibly busy museum full of people trying to glimpse some of the world’s most significant artworks and historic artefacts. After struggling to see the works on show in the rest of the galleries, she asked her curator if it was possible to get into the Met before everybody else, so that she could have the museum to herself. The curator said yes, so one morning, Kihara arrived at the same time as the security guards and the cleaners.

She found herself sitting in the modernist gallery, which housed the likes of Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Gauguin. Sitting on an ottoman in front of three Gauguin paintings, Kihara thought back to Ngahuia Te Awekotuku’s essay from a paper presented at the Gauguin Symposium in September 1992 at Auckland City Art Gallery, a symposium which commemorated the time Gauguin spent in Aotearoa on his way to Tahiti. In the essay, Te Awekotuku reflects on Gauguin through her Māori lesbian lens, and asks if his paintings are “tales of mahu trickery” (mahu being Tahiti’s third gender, often likened to fa’afafine). Sitting in front of those Gauguin paintings in New York, Kihara started to ask the same questions of herself, seeing faces and mannerisms that she recognised from people she knew, from fa’afafine. Could Gauguin’s work actually be a visual record of queer Polynesian life?

Inspired by Te Awekotuku, Kihara’s own thinking about this historical material shifted. She began looking for any kind of pre-colonial, historical, herstorical evidence of Pacific third-gender existence — something that she posits Gauguin’s paintings offer. “It’s very hard to find photographs of them [third-gender people],” Kihara tells me “but at the same time, many of these colonial photographs are staged for Western consumption.” The fact of being staged for Western consumption comes with Western impositions of heteronormative gender binaries, making it difficult for today’s audiences to discern the gender of the models. The photographer (or in the case of Gauguin, the painter) was projecting European understandings of gender on to the image. “These stereotypes are not just racial stereotypes, they are actually gendered stereotypes, right?” Perhaps fa’afafine and fa’afatama lives were right in front of Gauguin, but he couldn’t see them because of the worldview he was looking through.

But it’s not just through the eyes of a French man who died nearly 120 years ago that fa’afafine and fa’afatama experiences are rendered invisible — this still happens today, and in Sāmoa itself. The fa’afafine and fa’afatama communities are taken for granted, Kihara tells me. Revisioning histories to recover fa’afafine images, she explains, is “to build fa’afafine capital — that is, made by and for the empowerment of the fa’afafine indigenous queer communities”. And Paradise Camp is proudly about this recovery and revisioning. The reason this is so vital extends beyond the acceptance of any one person’s gender and is deeply connected to the way in which fa’afafine experience is excluded from many aspects of civil life, including climate-change policy.

Venice may seem a long way away from Sāmoa; however, these two places are both directly feeling the impacts of climate change and are perhaps closer than you might think. “Venice is a very fragile, precarious lagoon that is impacted by climate change, and so are the islands in the Pacific,” says Natalie King. “We went to Venice in November 2019, and we arrived the day after [the climate phenomenon known as] acqua alta, when the whole city had flooded. It was the most significant flood in 50 years.”

Sāmoa, too, is no stranger to flooding. Brianna Fruean, a Sāmoan member of the Pacific Climate Warriors, spoke at COP26 in Glasgow about the smell of mud left in her house after a storm or flood — the same reality Kihara would know, having lived in Sāmoa for the past 11 years. In her experience, climate change is quickly brushed off as a subject when she speaks about it with the New Zealand arts community. But as a resounding number of voices from around the world shared at COP26, climate change is about far more than the early-summer weather Aucklanders have just been enjoying. Living in Sāmoa, Kihara has seen the impacts of climate change first hand. She points to scientific evidence that suggests the country is experiencing sea-level rise of up to 4mm a year. Each year, cyclones and floods increase; and all of this is on top of the destruction of Sāmoa’s coral reefs in the devastating September 2009 tsunami.

In Paradise Camp, Kihara touches on the specific experiences of fa’afafine and fa’afatama with climate change, which are very overlooked. Our approach to climate change needs to be intersectional, she tells me, advocating for fa’afafine-inclusive climate-change policy, because of the different climate-change experiences felt by fa’afafine. Current approaches to foreign aid are based on heteronormative gender binaries, which leave out those who don’t conform to gender binaries. For example, Kihara tells me that after the 2009 tsunami, fa’afafine helped on the ground, but when they returned to the evacuation centres, they encountered bathrooms that were only for either men or women. So they found an abandoned house and set up their own centre with gas lamps. “It’s things like that nobody knows,” she says.

“Climate change is not going to go away, it’s going to keep happening, and we’re going to need more pragmatic support on the ground… so that we can feel comfortable. I really think that, together with evangelical Christianity, foreign aid policies that exclude the fa’afafine community are making our lives slightly harder.”

It’s clear to Kihara that the fa’afafine community need to be visible across all aspects of life, not just in conversations that have to do with gender. We need intersectional approaches to “foreign policy, climate change, education, prime industry, all of that”.

Yuki Kihara and Natalie King. Photo by Evotia Tamua

Natalie King tells me Venice is “exhilarating, but also an unremitting undertaking”. I don’t doubt that for a heart-beat. Given the size of Paradise Camp and the challenges of producing art at that scale during the Covid pandemic, the difficulties become very apparent. As I talk to Kihara, however, it becomes more and more clear that there is a whole other unremitting element to her participation. “I hope that by taking Paradise Camp to Venice, it sheds light on our [case] for visibility… It’s very unfortunate that we have to go to a really colonial place for us to be recognised in our own island, but people really take us for granted. I have to go to a place like Venice in order to be recognised here in Aotearoa, in Sāmoa and in the region.”

It is clear that Paradise Camp is informed by much archival research. The last time I actually saw Kihara in person was at Auckland Museum, when we were both doing research in the documentary heritage collection. She confides that the sustained archival research involved in her practice has meant she engages with a lot of trauma in dark rooms while wearing white protective gloves. She describes it as bleeding over and over again: “It can really fuck up your mental health.”

As I think about Kihara’s dealings with trauma while doing such research, and about her experience of living life as a fa’afafine, I am haunted again by those two words she uttered: like me. She has been a known and respected figure within the Pacific arts community for more than 20 years, one whose presence has been constantly felt, and whose confidence can sometimes seem intimidating. Listening to her openness now, hearing about the practical difficulties of fa’afafine life because of colonial impositions and anti-trans bigotry, and her views on the impending threat of climate change, I realise that what appeared as fearlessness might actually be resilience, a mode of survival. It’s easy to focus on Kihara’s career successes and forget about the violence regularly inflicted upon non-conforming people. Suddenly, her hard exterior makes sense, because this shit is hard.

But rather than lingering in such places of hopelessness, Paradise Camp is a built universe in which gender and sexual expressions are no longer seen as being binary, but rather where everyone is free to express their cultural identity without fear, without discrimination, without being ostracised and demonised. Referencing the way in which European men painted and photographed their ideas of gender on Pacific bodies, Paradise Camp peels that back, creating a world that Kihara herself would want to be a part of. This new world offers solace to Kihara and her communities.

More than 80 people in Sāmoa were involved in the exhibition’s creation. It was important to Kihara to up-skill her own communities during the process. The work was made by the fa’afafine and fa’afatama of Sāmoa, its primary audience. It’s clear when talking to both Kihara and King how important it has been to bring others with them on the Venice journey. “The opportunity is Yuki’s but it extends to many others,” the latter says.

One such person was arts writer Ioana Gordon-Smith, who was brought on as assistant curator (Pacific). Remembering her reaction to news of her selection, Gordon-Smith says it was more than just excitement. “It was this feeling that you can’t overlook Yuki.”

“Pacific art in New Zealand,” Gordon-Smith explains, “has been thriving now for decades, and Yuki’s selection represents an overdue moment of endorsing a Pacific artist as the representative for New Zealand.”

There’s a lot to be proud of in Paradise Camp, and Kihara is most proud of the involvement of the fa’afafine community in Sāmoa. “I don’t know what Sāmoa is going to be like in the next 100 years,” she admits. “I do hope that we are still using the term fa’afafine, but if not, then the topic of fa’afafine is now part of the New Zealand canon.”

For King, it “reminds me how two people like Yuki and I who come from such totally different backgrounds can come together and can do anything. We are soaring.”

It would be easy to regard Paradise Camp as a work solely about gender, but that would be a mistake. Kihara is advocating for a world in which fa’afafine, fa’afatama — all genders, in fact — are not only accepted, but have their full humanity recognised across all facets of life. The exhibition is not just about gender, but also about how gender intersects with everything else, about how we can do better.

“You’ve got range,” I say to Kihara as our call is about to end.

“I’ve got range,” she replies.

–