Aug 21, 2015 Art

This story first appeared in the July 2015 issue of Metro.

In the Berlin neighbourhood of Kreuzberg, the post-winter buds have popped and the nascent growth glows neon against a plane-streaked sky. To look up is glorious. Things at street level, though, aren’t so pretty. All of the banks, pharmacies and supermarkets along Kottbusser Damm are boarded up. Locals have moved their cars to other parts of the city, and several blocks are kettled by cops in riot gear leaning against Polizei paddy wagons, tools for crowd dispersal at the ready. It is May Day.

Every year, Kreuzberg is the centre of Berlin’s anti-capitalist protests. Sometimes things get ugly: car windows smashed, flags burned, bottles and paving stones thrown. But this year is tame. Entrepreneurial young Turks — the children of first-generation migrants brought to West Berlin as cheap labour in the sixties — set up portable grills and mix makeshift mojitos for the mainly white, mainly middle-class marchers. It is Occupy-chic; in the 20th century’s most avant-garde and politically traumatised city, the physical and psychic dividing lines between left and right have gone, and the aesthetic of collective action has somehow managed to replace its disruptive force.

But Berlin, these days, is a town where aesthetics really matter. Over the past two decades, it has become the centre of the European art world. Now, heavy-hitting dealer galleries are a major force in the city’s gentrification. Those big dealers need big collectors. Those big collectors like buying big artists. And around it goes.

The eye-watering economics of the international art world is neoliberalism’s greatest high-cultural achievement. This has also created a deep paradox for those of us who make our living within it: the extent to which we can really claim a critical position when our sources of income are no different from property developers or investment bankers. Just like all those white kids dancing with their cocktails through Kreuzberg, the defining intellectual question artists now face isn’t the extent to which what they do is a critique of capital. It’s how they navigate the relationship between critique and capital.

Simon Denny is one of those artists. No New Zealander has conquered Berlin, or the international art system, as he has. He is one of the most celebrated and influential young artists on the planet. And his ambitions and successes are outstripping anything the country of his birth can meaningfully provide.

Which is what makes him the perfect person to represent us at the 56th Venice Biennale — the oldest and most important art event in the world. Though its arcane structure suggests it’s about “nations”, Venice isn’t about nationality at all. It’s a global temperature gauge, a place the entire art world descends on every two years to make new discoveries, draw new connections, and very occasionally, have our collective ground shifted. Borders have nothing to do with it.

So when Denny was picked, many insiders saw it as a no-brainer; if a New Zealander were ever going to leave a mark on this event, he was the one, at this moment, who could do it.

New Zealand’s mainstream media took the bait, although there was very little of the usual axe-grinding about art world pretension and wasted taxpayer dollars. Instead, there was a kind of cautious fascination with Denny, his stratospheric early-career achievements, and most of all, his work: all those ugly, research-heavy installations about the redesign of New Zealand’s passport, Munich tech conferences, Samsung’s corporate philosophy, or the Kim Dotcom raid.

That calm media curiosity held even as details of his Venice project emerged. Using Nicky Hager’s 1996 book Secret Power as his starting point, Denny planned to examine material from the Edward Snowden leaks and New Zealand’s role in the Five Eyes security network. Hager himself was going to be a special adviser. News then followed about the venues: the Marciana Library on Piazzetta San Marco, and Marco Polo Airport. Both were hands down the most prominent sites New Zealand had ever secured at Venice.

It had all the swagger, confidence and smarts that have made Denny one of contemporary art’s brightest stars. But, here’s an admission: I have always held quiet doubts about his practice. At his best, I think he’s an amazing sculptor. But I’m less convinced by the way many writers and supporters frame him as a kind of edgy techno-polemicist, just because of the zeitgeisty content he draws upon.

Denny has said he doesn’t take up a singular political position in relation to his subject matter; he simply holds up a mirror to the culture around him. This has often struck me as a strategic ambivalence that makes him equally palatable to the collectors complicit in the economic systems he puts in play, and the new art world hipsters who like to pretend they’re not.

With Snowden and Five Eyes, Denny was in seriously dangerous political territory, on the biggest stage in the world. Snowden, frankly, is not something you muck around with.

So, three days after May Day, as I flew from Berlin to Venice for Denny’s big reveal, I had only one question: given the magnitude of Snowden’s leaks, could Denny actually add anything critical to our understanding of government surveillance, its impact on our lives, and our complicity in it?

The answer, as I walked through sliding doors into one of the grandest rooms in Europe — a room Denny had filled with server racks, office desks, diagrams, infographics and national flags — was crystal-clear within seconds.

For two years, Denny has had the local and international press eating out of his hands. He has been the master of his own narrative. And almost all of the coverage has fixated on his age: Denny was born in 1982. This is usually framed as an “oh wow, look how young he is” factoid. But it’s far more important than that. It’s the key to understanding why — or if — Denny matters.

Denny represents a generation (mine, admittedly, so I’m biased) whose formative years were bracketed by two defining events: the moment, in 1989, when an East German official accidentally reconnected the world, and the decision, 12 years later, of a group of men, some not much older than us, to fly planes into a pair of skyscrapers.

In between, we were shaped by the quickest technological revolution in human history. We aren’t the digital natives. We’re the ones just before them, born on the cusp of X and Y into the nuke-infested geopolitics of our Boomer parents but raised in an age when machines with screens first showed us the world, then connected us to it in ways we never imagined, then became worlds in themselves.

This hasn’t just changed how we receive information. It’s changed how we see.

We’ve watched the world become one giant circulatory system dependent on uninterrupted flow: of currencies, capital, labour, images, ideas and human beings.

We’ve watched the world become one giant circulatory system dependent on uninterrupted flow: of currencies, capital, labour, images, ideas and human beings. We’ve witnessed what happens when that flow grinds to a halt: the seizures caused by 9/11, by the global financial crisis, by WikiLeaks and Snowden. And, lately, we’ve seen how terrified the West becomes when the circulation itself is hijacked by forces beyond its control: the possibility of Ebola’s exponential spread if someone coughs up blood at Heathrow; the dark appeal of Islamic State; the black tide of Africans flooding the Mediterranean, testing Europe’s open borders and its humanitarian tolerance.

Denny is both a product and manipulator of that flow: his art world ascendancy is a masterclass in how to create global momentum. But he has also recognised that the free-market idealism he has so deftly exploited has a shadow-side: the creation of the most extensive surveillance system ever imagined, a system his own country is a part of. In Denny’s universe, opportunity and oppression aren’t separated by a wall; they’re fuelled by exactly the same information, and run on the same technological networks.

Marco Polo Airport — named, obviously, after one of the early heroes of globalisation — was the first Italian airport built after 9/11. The Marciana, meanwhile, is one of Venice’s most historic sites. Designed by Jacopo Sansovino and decorated by the greatest Venetian painters — Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto — it’s a space that shifts between architectural reality and painted illusion. Its soaring ceiling has tromp l’oeil effects designed to double its height. Around the walls, figures of philosophy and charity and faith stand in scalloped alcoves that don’t actually exist. It’s a giant hall of mirrors — an allegorical trick in which its decoration is a humanistic doppelgänger for its political function, as the official repository for Venice’s knowledge of the world at the height of its Renaissance influence.

Denny’s intervention in the Marciana initially seems horrifyingly cold and corporate. Viewers enter through sliding glass doors and a transparent portal, on one side of which are the Five Eyes national flags and on the other a bizarre upside-down illustration of New Zealand. The main part of the room is filled with two lines of “modded” computer server racks. Between the rows are two magnificent globes: Vincenzo Coronelli’s 1688 representations of the celestial and terrestrial worlds.

In a clever parallel to the “wunderkammers” of early museums and libraries, Denny has turned his server racks into elaborate display cases. One row is filled with objects that are all some sort of reiteration, translation or stand-in for an image from a Snowden-leaked slide. Denny has collated these into themes: imagery about the US National Security Agency’s “Treasuremap” program, for example; the GCHQ spy agency’s instructions on the “Art of Deception”, slides explaining invasive computer programs with creepy names such as “Foxacid” and “Mystic”.

The case that deals with invasive programs contains horrible Perspex bar graphs, a giant image of a wizard holding a cellphone-topped sceptre, fantasy playing cards, and transparent cartoons of acid barrels. At its centre is an eagle, its wings spread and bursting through the top of the box. Clutched in its talons is a roped-up globe. It is Denny’s translation of a seminal NSA graphic, in which America’s national bird grips the undersea cables that connect the world. The original image is one of the most insidious emblems of the NSA’s desire to “collect it all”. Denny’s version, lifted from two dimensions into three, is even stranger and more ridiculous.

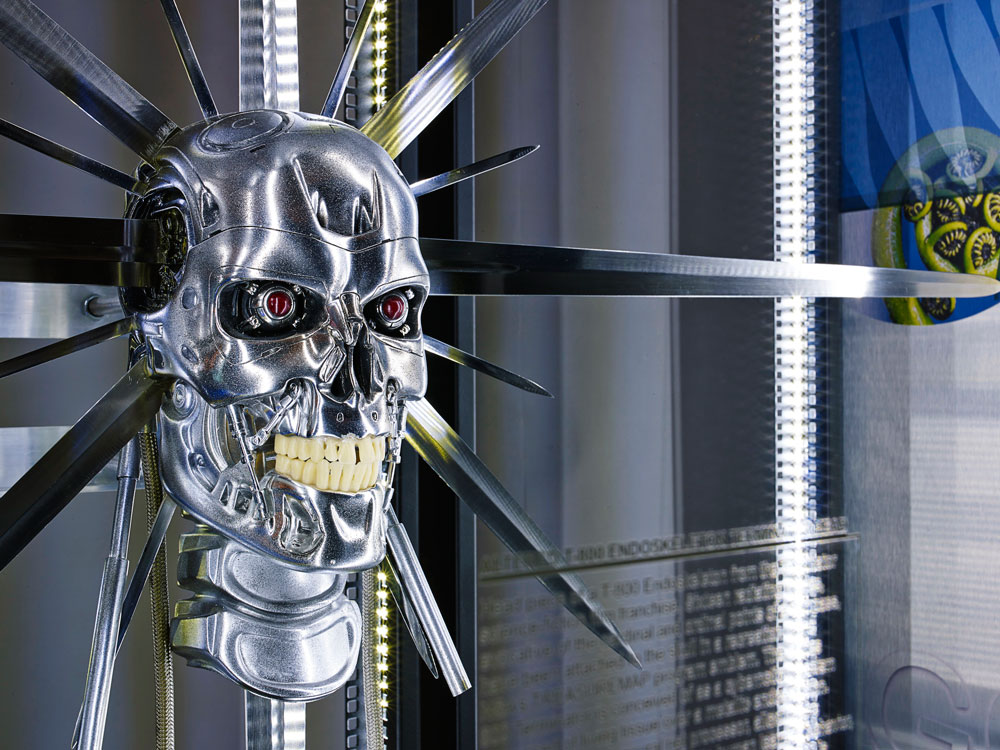

He performs a similar transformation in the “Treasuremap” rack. The Treasuremap revelations were some of Snowden’s most shocking: here was a program that gave the Five Eyes partners the ability to map the entire internet, and every device connected to it — a tool for total, unaccountable omniscience. At the dead heart of Denny’s cabinet is the head of the T-800: the iconic robot skull from Terminator 2. For anyone who grew up in the nineties, it’s a pop-culture image with the force of a religious icon. In Denny’s version, pristine sword blades emanate from it in a starburst, a halo of cold steel.

It’s Denny’s interpretation of one of the most disturbing examples of the NSA’s visual culture. Terminator 2 is a film about the unintended consequences of technology; it suggests that in advancing so quickly, we’re creating the potential for machines to strip us of our human freedoms. Remarkable, then, that the NSA would choose as its logo for its most breathtakingly oppressive program a robot skull with glowing red eyes that looks almost exactly like the Terminator.

What Denny does so effectively here is short-circuit the NSA’s narrative by turning its own imagery on itself. And through his process of intense aggregation, he creates new networks of meaning. Alongside the T-800, for example, there are tiny Macs, cellphones and human beings, all lifted and laid out exactly as they were in Treasuremap slides. Elsewhere, there are Warhammer figurines, references to gaming culture, images of Penn and Teller, translations of flow-charts, graphs and other forms of nerdy data and infographics.

It’s easy to describe it as dystopian: evidence of a nefarious la-la-land in which our NSA overlords use gamer and sci-fi archetypes to cloak their activities in fantasy. But Denny also shows us that it’s highly effective design. The NSA slides weren’t made to brief Black Ops tough guys on a sensitive mission, or convince grey-haired senators of an invasion’s merits. They were made to inspire hackers, geeks and programmers, a lot of whom grew up playing Dungeons & Dragons, watching sci-fi, clocking Doom, and abusing one another on 4Chan.

The pop references, then, aren’t flippant or accidental at all. They are targeted, precise and extraordinarily significant for the young men and women on their intended receiving end. People like Snowden, who, it’s easy to forget, is even younger than Denny. The NSA wants the hackers on its side.

The amount of visual information is overwhelming. Denny’s use of transparent materials such as glass, Perspex and plastic, along with blue-ish backlighting, makes the racks’ internal spaces even harder to comprehend. They are disorienting and repellent — boxes we can see straight through but that also push back out at us. Cartoon wizards and TV magicians bounce off bearded Tintoretto gods. And yet everything is incredibly still. Denny has frozen it all, stopped the information’s flow. You can practically hear the room creaking in his grip.

At the heart of Secret Power is a single question: who was the design genius behind the NSA slides?

In searching for the author of the Snowden material, Denny’s design collaborator David Bennewith discovered David Darchicourt, whose LinkedIn profile stated — as though it were the most ordinary thing in the world — that he was creative director of defence intelligence at the NSA from 2001 to 2012. These days, he’s a designer for hire. And like many freelancers, he puts his portfolios online as a way to hustle for work.

Denny and Bennewith raided Darchicourt’s portfolios and gave them the same treatment as the Snowden slides. The second group of server racks are filled with the results. Among them are sculptural re-interpretations of exhibition displays for the “National Cryptologic Museum”; wacky motivational board games; and Darchicourt’s LinkedIn self-portrait — a computer-drawn caricature made monstrous in three dimensions. The links between Darchicourt’s freelance work and the visual language of the Snowden slides are obvious: if he wasn’t making them himself, he was almost certainly involved in setting the brand guidelines.

Darchicourt was clueless about what Bennewith and Denny were doing, even when they hired him to make new illustrations about New Zealand. The largest of these is “a world-map commissioned with New Zealand as the centre and south at the top”. In it, New Zealand takes up most of the globe. Key tourist attractions are identified with cartoons — the Cape Reinga lighthouse, SkyCity, Rotorua’s hot pools, Kaikoura. Sally Field hovers over Dunedin as the Flying Nun. And in a knowing wink to Hager, Waihopai is marked, while red lines denoting submarine cables link Aotearoa to Australia and the US West Coast.

And the reason south is at the top? Just before you enter Secret Power, you pass through a vestibule where there is a beautiful 15th-century map by Fra Mauro. It is one of the first attempts to map the world, and south is where north should be; the world is upside down. It is the first point on an essential linking thread – from Fra Mauro, through Darchicourt’s absurd interpretation of New Zealand’s place in the world, through Coronelli’s globes and that extraordinary eagle clutching our networked planet.

Secret Power is the most formal Denny has ever been, a rigid installation made up of spheres and boxes and lines. And yet within it, he shows us that the world no longer has an up and down, a left and right, a then and now. Everything is visible, all the time; everything is connected; everything is information to be exploited.

The Marco Polo project is far less successful. Denny had the entire ceiling of the Marciana Library photographed and printed at a 1:1 scale on adhesive vinyl, which was then applied to the airport’s floor so that it ran across passport control and through to the baggage hall. It is vast. Every day for months, tourists trundle their wheelie-cases across it.

Denny is making a point here about how these transitional zones grant us the freedom of movement while simultaneously tracking and examining us at every step. While this clearly connects with the overarching themes of Secret Power, it also feels an awful lot like stating the obvious. Its most interesting aspect is pointed out by both Denny and the writer Chris Kraus in the lavish Secret Power publication, where they remind us that Snowden spent more than a month living stateless in the transit zone of Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport. But it’s a connection the work itself doesn’t lead us to.

Involving Hager himself at the height of the Dirty Politics scandal added nothing, and cast the journalist as a glorified fact-checker.

I’m also unconvinced that Nicky Hager needed to be involved. There’s no question his Secret Power was vital background for Denny. But it was source material, in exactly the same way Snowden’s slides and Darchicourt’s designs were. Involving Hager himself at the height of the Dirty Politics scandal added nothing, and cast the journalist as a glorified fact-checker. It was a clunky move for both men.

But these are minor criticisms. I’m convinced: Simon Denny is a major artist.

Denny’s innovation comes from his committed lack of imagination. He doesn’t make anything up, ever. All of his material is sitting there, on the internet, waiting for someone with his synthetic capacities to come along and see the connections. It’s pattern recognition of the highest order.

He has also pioneered a form of collage using the logic of screens, and layers. In digital environments, objects can be spun in any direction to reveal new views and yet remain complete. Denny does that too, not by lifting information from behind the screen but by sucking forms through it, allowing us to witness their warping and weirdness as they move from the code-produced dimensions of the machine world into the actual dimensions of ours.

There’s nothing ambivalent about this; in fact, it’s highly aggressive. Denny is nihilistic and destructive. He is capable of knocking images off their axes and planets off their poles. He’s a hacker of real space; he likes to break things and see how much physical chaos he can cause. His political and cultural radicalism has nothing to do with his content, and everything to do with his formal power as a sculptor.

What he has done in Venice is brutal and terrible. But it is also brilliant and beautiful, and it has changed the way the world looks at this country, and the art we make.

Read Henry Oliver’s story about working the parties of the Venice Biennale here.