Sep 26, 2016 Art

We know New Zealand art is a thing. The question posed by the Walters Prize is how the hell do we go about defining it?

Surging up every two years, the Walters Prize is a crucial barometer for the health of the contemporary art scene and a flashpoint for debates about what we value as “New Zealand art”. People really do argue about the prize — a lot — which is surely a measure of its success as an event and an accolade.

One of the perennial talking points is how the jurors who decide the shortlist have gone about their business. The 2012 jury, for example, copped plenty of flak because the four finalists — all Auckland-trained, all young, all exhibiting overseas — seemed an extremely narrow view of New Zealand practice. And in 2014, much of the attention fell on the selection of finalists Kalisolaite ‘Uhila and Luke Willis Thompson, artists whose timely projects engaged with questions of what “home” means in New Zealand’s largest, most ethnically diverse and cripplingly expensive city.

This year is no different. Which is to say it’s extremely different but, in its own way, just as focused. The finalists — Lisa Reihana, Joyce Campbell, Shannon Te Ao and Nathan Pohio — all work primarily in photography or video, and all of them address questions of history and place in their practices. It’s a selection, I think, that shows a jury reflecting seriously on the question of what New Zealand art is, and what it means to make a significant contribution to it. It’s not quite a manifesto. But it’s certainly a strong statement.

And it’s not a statement I completely agree with. For me, it feels too close to home, given some of the major achievements by overseas-based artists in this Walters cycle. Locally, too, there were several projects which, though less content-heavy than the four finalists, had major impacts on their respective disciplines.

But what I do like about this year’s selection is how much I have to wrestle with it — and that four very good artists have been given a shot at the prize.

The exhibition begins in Auckland Art Gallery’s Kitchener St forecourt, with Pohio’s billboard-scale photograph Raise the anchor, unfurl the sails, set course to the centre of an ever setting sun! (2015).The historical image shows a group of Kaiapoi Maori on horseback escorting Lord and Lady Plunket, in their motorcar, onto the Tuahiwi reserve and marae. Of the finalists, Pohio faced the biggest challenge to restage his work in Auckland, because its original Christchurch placement was such a specific reference to his home city’s colonial past. But the presence in the AAG’s collection of a Lindauer portrait of the Kaiapoi rangatira Hakopa Te Ata o Tu has provided a perfect link for him between inside and outside, and between South and North.

The rest of the show is dominated by three large video installations, all inflected with a kind of romantic narrative intensity. I’m deeply biased towards the first of them, Te Ao’s two shoots that stretch far out (2013-14), having put it on the cover of my book. I think it’s one of the most significant works made in this country in years.

Te Ao’s starting point is the English translation of a Ngati Porou waiata, in which a woman describes her pain as her husband takes another wife. In five separate shoots, Te Ao reads it, in slightly vary-ing versions, to animals: a swan, rabbits, a wallaby, chickens and ducks, and a donkey. It’s a complex, subtle reflection on the mythical intersections between language, sex and shapeshifting, as Te Ao, taking up the voice of a heartbroken woman and trying to communicate with animals, enters an unstable, semi-shamanic space. He has paired the films with a new installation made from dozens of potted outdoor plants, which will be tended for the duration of the exhibition — a complementary empathy to that he shows his animals.

The best-known nominated work is Lisa Reihana’s in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015) — last year’s massively popular video installation, which earned her the 2017 Venice Biennale slot. For the Walters, however, she is presenting a different piece, Tai Whetuki — House of Death Redux (2016): a dark, ceremonial reflection on death and mourning filmed at Karekare, near the site of an 1825 massacre. Shot in a more conventionally cinematic way and with fewer digital tricks than iPOVi, it has nonetheless been conceived on a similar scale: two big projections, the floor of the room covered with a shiny surface so the films are reflected in wavy reverse. It builds from iPOVi in the sense that it picks up the figure of the chief mourner from the earlier work. But it is a wildly different undertaking, and a big punt, too, given the success of its predecessor.

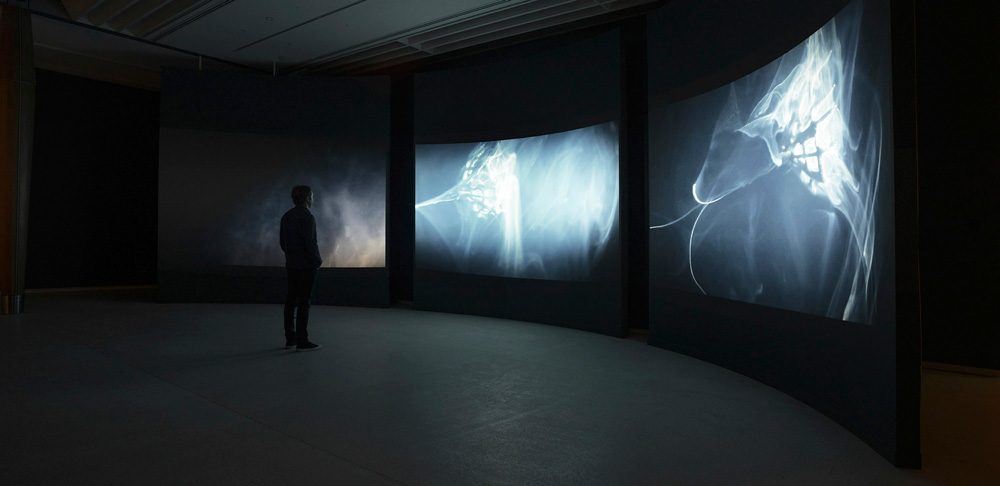

Joyce Campbell’s Flightdream II (2016) reaches the farthest from New Zealand’s coastline, down into the Marianas Trench. One of its most interesting aspects is its generative circularity. The video installation builds from a short story by the science fiction writer Mark von Schlegell about encountering monsters deep in the trench, which was itself the writer’s response to an early series of photos by Campbell, called Marianas. Across three projections, strange, silvery forms drift through black water releasing colloidal emanations while a voiceover reads a new version of von Schlegell’s story, accompanied by a brilliant, jarring soundtrack from experimental musician Peter Kolovos.

It feels more like a curated exhibition than a noisy, dissonant prize.

It’s a tight show, slickly installed. And it will introduce the wider public to three artists — Campbell, Pohio and Te Ao — they’re unlikely to have heard of before, which is one of the central functions of the Walters. I suspect it will also be a very popular exhibition, because of its narrative accessibility and the fact that the art in it so clearly belongs in this part of the world.

But with the increasing maturity of our local scene, the amount of contemporary art being made, and the number of artists working at consistently high levels internationally, it feels — as 2012 did — more like a curated exhibition than a noisy, dissonant prize. This says more about what the wider art community is currently grappling with than it does about the individual projects.

We know that New Zealand art exists — that it’s a thing. The much bigger question, as this Walters iteration illustrates, is how the hell we go about defining it.

The Walters Prize 2016, Auckland Art Gallery, until October 30, free. www.aucklandartgallery.com

Anthony Byrt’s book, This Model World: Travels to the Edge of Contemporary Art (AUP, $45) is available now.