Oct 12, 2018 Art

Gordon Walters set the bar so high for abstract painting that few other New Zealand artists have ever come close to clearing it. A major new book and exhibition make the case for his greatness. But do they get us any closer to understanding the man behind the koru paintings?

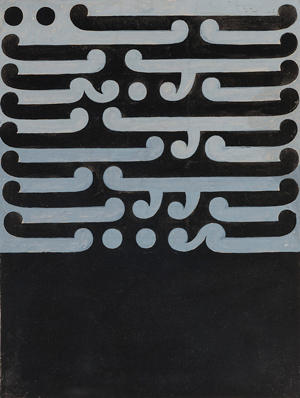

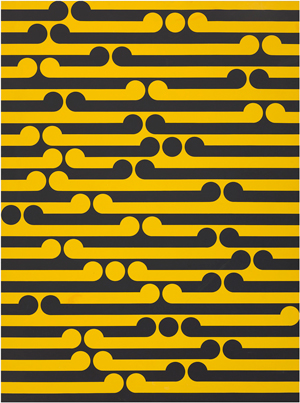

Years later, the men would fall out over Walters’ most famous works. If you don’t know Walters’ koru paintings, you’ll certainly know the Walters koru, as a logo for organisations such as the New Zealand Film Commission: a stylised, ultra-modernist reduction of traditional kowhaiwhai, distilled to a simple bar-and-ball shape. This basic unit transformed Walters’ work, allowing him to explore, over the following decades, the painted surface as a space for “push-and-pull”, on which it was impossible to know what was figure — on top — and what was ground — underneath.

The koru paintings turned Walters into a giant of 20th-century New Zealand art, rivalled only by Colin McCahon for the length of shadow he threw. New Vision, which opens in July at Auckland Art Gallery (having already been shown at Dunedin Public Art Gallery), tells a bigger story about Walters than just the korus. It’s a grand survey from the 40s through to the artist’s death in the 90s, which makes the case that he was, above all, a dedicated formalist: a man who believed deeply in the potential of non-representational art and who spent a lifetime reducing a handful of forms — of which the koru was one — to their purest essence.

And it does the job convincingly: there’s no doubt, when you see Walters en masse like this, that he was one of our greatest painters, with a far more diverse practice than he’s usually given credit for. But for all that, there’s a figure lurking in the background of the project who seems to want to spring forward but never quite emerges from the shadows: the man himself.

One of the curators, Julia Waite, has also researched a scrapbook Walters began around 1951, filled with cut-out images of modern and “primitive” art from around the world: a classic “Family of Man” universalist modernism typical of the era, which framed all the world’s art — Western or otherwise — as a possible source to be mined for his own. Laurence Simmons, another curator, even gives this a name: Walters’ approach, he argues, could be seen as “polyphonic modernism”.

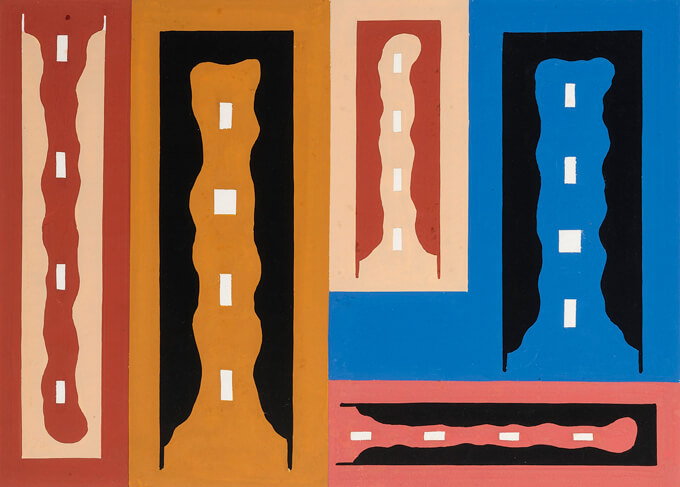

As well as three essays from curators Waite, Simmons and Lucy Hammonds, five more from local and international art and architectural historians look at different threads in Walters’ practice. Luke Smythe writes about the influence of surrealism; American heavyweight art historian Thomas Crow writes about Walters in relation to international hard-edged abstraction. Australians Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson do some great detective work figuring out precisely what abstract paintings Walters might have seen in Paris and Amsterdam around 1950. But the standout is Peter Brunt’s essay on the influence of Pacific art on Walters, in which he brilliantly links some of Walters’ most abstract works — bands and boxes of solid colour — to Marquesan tattoo and other Polynesian motifs.

As a map of what Walters was looking at and when, and how this might have shaped his “new vision”, the book is full of information, some of it genuinely revelatory. And yet the format — eight thematic essays, none longer than about 4000 words — also highlights a systemic issue. New Zealand art history has a biography problem: a prudish formalism that bulldozes over the mess of ordinary lives, then presents itself as a sophisticated truth. Life continually plays second fiddle to the art — or more specifically, to the rigidities of academic art history and the fly-by horrors of the short essay. Open any major gallery publication from the past five years in this country and you’ll find the same thing; it’s an endemic formula, fast turning into an orthodoxy. And it is, I think, letting our best artists down.

It’s a dangerous game for a reviewer to say what something should have been, rather than dealing with what it actually is. But because major retrospectives and their accompanying books come along so rarely, they tend to have an authoritative force in New Zealand, which can last generations.

Hammonds, whose essay is a potted biography, points out that the book was never intended to be a detailed account of the artist’s life, but rather to introduce the public to the full breadth of themes in Walters’ practice. Fair enough. She also argues out that it leaves plenty of biographical breadcrumbs for other researchers to pick up. The question I have is whether those breadcrumbs might actually have made a better meal and moved us closer to a true understanding of what was making Walters tick, and where — and who — he was getting his ideas from.

When Walters held his second koru-painting exhibition in 1968, Schoon wrote in the New Zealand Herald that “the history of the paintings by Gordon Walters begins with me. It is based on my 10 years of field work.” Walters replied that although he was certainly using a Maori motif, he was using it with “a logic quite foreign to Maori art”. He also countered Schoon’s central claim, writing that in fact, “Schoon pored over my work. He requested and was given my permission to use the motif which occurs in my recent paintings.”

Walters travelled extensively in the late 40s and early 50s. He lived in Sydney from late 1947 to early 1949. There, “he connects with the city’s artistic and bohemian set”, the book’s chronology tells us, and falls for Dorothy Henry, a divorced life model with two daughters, with whom he ended up having a long relationship. He went to London for a year in 1950, with trips to Amsterdam and Paris. Then, in 1951, he moved to Melbourne, where he started to make abstract work and connected again with Henry, who was living in Hobart. In 1953, Walters had a fight with another man over Henry. Rather than stick around to try to patch things up, he left abruptly for New Zealand — where he pressed on with abstraction, saw Hattaway’s drawings, and eventually began to develop the koru motif.

As Hammonds says, these breadcrumbs are all there in the book. But none of them are followed to the end of the trail — there’s a consistent deference to what Walters was looking at rather than how he was living. And yet his chronology is filled with cracked doorways crying out to be crashed through: the friendship and rivalry with Schoon; hanging out with Sydney’s bohemian set; falling in love with Henry, scrapping over her, and coming home in a huff with a broken heart; pinching a committed patient’s motifs. Later, Walters married the great Maori studies scholar Margaret Orbell, with whom he would share the rest of his life, raise a family and work alongside on the seminal publication Te Ao Hou.

It’s my firm belief that we’re far more shaped by who we love and fuck and who we lose and hate and how our hearts are broken than by paintings we might have seen in a gallery in Europe or an art magazine. It also strikes me that a contemporary revision of Walters isn’t complete without a genuine, lengthy attempt to assess his relationship with Schoon, if only to finally draw a line under it. So, too, Orbell’s integral place in Walters’ life and thinking.

The artist Chris Heaphy, who became close to Walters not long before his death in 1995, also believes the retrospective exhibition format means some of the key influences and moments in Walters’ life have been downplayed. One of these was the “appropriation debate”, which sprang up in the 80s and 90s around Walters’ use of Maori forms.

In 1986, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku had called Walters’ appropriation of kowhaiwhai and other Maori forms “damn cheeky” for the way it rode roughshod over their cultural significance, for the sake of his own formalism. Then, in 1992, all artistic hell broke loose around the exhibition Headlands: Thinking Through New Zealand Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. In the accompanying publication, the young curator and art historian Rangihiroa Panoho had written an essay that similarly questioned Walters’ formalist appropriation of Maori motif. In response, several Walters supporters, most prominent among them the art historian Francis Pound, rallied around the artist.

The incident is dealt with too briefly in the new book. In her essay on Walters’ appropriation of Maori iconography, Deidre Brown writes that “[e]ventually the main protagonists in the debate, Te Awekotuku and Panoho on one side and Pound on the other, moved on to other intellectual concerns and the appropriation debate faded away from academic art history”.

It depends how long Brown thinks “eventually” is, but I disagree. The Headlands debate shaped a generation of artists, critics and art historians (myself included; I was taught in the late 90s by Pound and Panoho, both then in Auckland University’s art history department). It raised the stakes for all of us and forced us to look at our own positions, particularly at a time when the discipline was dominated by white middle-class men.

Panoho had every right to raise his concerns about Walters’ use of Maori motif, and did it at a moment in which postcolonial thinking was starting to reshape museums and galleries around the world. Nor did his argument necessarily negate the quality of Walters’ koru paintings. To my mind, it made them more complex; thornier examples of a peculiarly local modernism — it was the Maori content, after all, that placed Walters’ work as so distinctly from here.

But both Panoho and Walters were let down by Headlands’ organisers. Walters was blindsided; he showed up in Sydney for the opening and hadn’t been given any heads-up about the critique. And in Headlands’ aftermath, Panoho was largely left to fight his own corner, and faced a sustained, coordinated attack from some of the most influential figures in New Zealand art history.

Heaphy says Walters was deeply hurt by Headlands, but also recognised the irony that it had given his work a new prominence and popularity. Suddenly, he was like McCahon: someone younger artists needed to deal with, and to. This, as Andrew Paul Wood rightly points out in his review for the EyeContact website, is another aspect of Walters’ life story largely missing from the new book: his influence. The debate about Walters was crucial to Shane Cotton’s clever re-appropriations of white Australian and New Zealand artists; to the waka/aeroplane forms in Peter Robinson’s controversial “percentage paintings” that so resemble Walters’ korus; and most obvious of all, to Michael Parekowhai’s Kiss the Baby Goodbye, his kitset version of a 1968 koru painting.

More than that, the debate supercharged a generation of young artists who had either been grappling with how to express their Maori identity or were discovering it for the first time. Heaphy was one of them. He and Walters formed a close friendship in 1994. They’d paired up for the George Hubbard-curated exhibition Stop Making Sense at City Gallery Wellington, which — again, bobbing in Headlands’ wake — put Maori and Pakeha artists together to make new work.

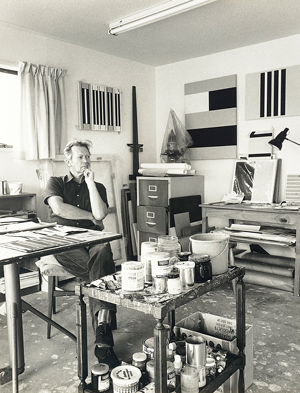

At first, Heaphy had been almost too intimidated to ask Walters to work with him. In the end, they made several paintings together, and spent an enormous amount of time in Walters’ studio. Heaphy also helped Walters organise his archive, which would eventually become so crucial to this exhibition and book.

Times had changed: modernism had tipped into postmodernism; the Treaty had turned 150 just a few years before and there was a new sense of questioning the embedded colonial power relations in New Zealand culture. Walters’ korus were part of that, without question. But, Heaphy tells me, Walters was also frustrated towards the end of his life with the way his non-koru work was perceived and valued, particularly as he saw paintings by the likes of McCahon and Tony Fomison fetching enormous prices.

And yet Walters resisted the easy option: to churn out endless new koru paintings. Instead, he stayed deeply committed to his particular brand of hard-edged abstraction — a formalist to the last. Heaphy says Walters was also excited and impressed by the young artists emerging around him — a modernist whose vision was still sharp enough to recognise talent when he saw it.

Stop Making Sense opened in May 1995. Heaphy believes it was an important and happy moment for Walters, after the Headlands storm. Six months later, he died. He was 76 years old.

But newness — and potentially, greatness — comes in that moment of translation, when an artist summons all those influences and unleashes his own singular force. Walters did that, and left us with a profoundly important body of work; hard-edged abstraction that no one in this country, still, has come close to.

New Vision is a hugely significant exhibition, accompanied by a vital new body of scholarship. But there’s another, equally important book that needs to be written about Walters; so far, his story is only half-told. The quiet refinement of an art work shouldn’t throw a blanket over the fires that produced it. And nor should we.

Gordon Walters: New Vision, Auckland Art Gallery, July 7-November 4, 2018.