Oct 8, 2019 Art

Thirty years before #metoo, the Guerrilla Girls were calling out misogyny and inequality in the art world.

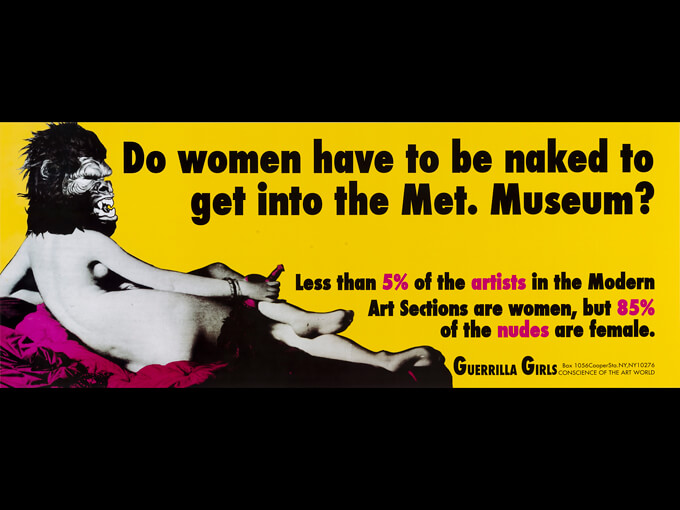

It’s one of the great art works of the late 1980s. Printed on a yellow poster, a nude woman lies with her back to us, her twist offered up as a permanent, erotic invitation to her (presumed) male viewer. Except, in this case, the temptation has been hacked. Instead of the woman’s original, pristine face — she’s the Grande Odalisque, by 19th-century figurative genius and soft-porn master Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres — this beauty is wearing a gorilla mask. “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” the poster asks. Then, the answer: “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

The poster is signed by the Guerrilla Girls, a pseudonymous group of activist women artists in gorilla masks, formed in 1985 to call out the New York art world’s runaway misogyny and inbuilt racism.

The 1970s in New York had been a time of breakthroughs, with feminist art, performance and conceptualism creating spaces for women and people of colour beyond the lily-white halls of the city’s powerful museums. But by the early 1980s, the free- market model had caught up with contemporary art. That market loved painting — the bigger the better — and most of all it loved big paintings by white dudes: Julian Schnabel, David Salle,

Francesco Clemente, Peter Halley, Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and many others less memorable. The Guerrilla Girls collectivised in response and became the “conscience of the art world”, making posters that scrutinised inequalities in contemporary art’s eco-system — often to brilliant, embarrassing effect.

Since March, Auckland Art Gallery has been showing Reinventing the ‘F’ Word — Feminism!: a substantial exhibition of the Guerrilla Girls’ work built around the Portfolio Compleat, a set of Guerrilla Girls posters from 1985 through to 2016 that AAG acquired in 2018. Curator Emma Jameson has worked closely with the group to make a show that emulates how the posters would originally have been encountered. The danger here is the potential for a kind of karaoke effect: original gestures of critique softened by the passing of time, cooked down to pastiche. Except that the issues the Guerrilla Girls highlighted as early as 1985 haven’t gone away — and still plague the art world today.

“What has changed is the consciousness of people who think about art,” one of the Guerrilla Girls, “Frida Kahlo”, tells me. “No longer would anyone even try to claim that it’s possible to write the history of our culture without including all the voices of the culture in the story. However, market forces that control the business of art are still dominated by big money and mostly white men. There’s the dilemma. We live in an era that aspires to democracy, but our art world is still run by the equivalents of kings, queens and emperors: a few with money and power tell the rest of us what our history is.”

The Guerrilla Girls have routinely skewered that royalty, or exposed its nakedness publicly. “These galleries show no more than 10% women artists or none at all,” reads one poster from 1985, above a list of offenders. “How many women had one-person exhibitions at NYC museums last year?” asks another from the same year (the answer: a measly one, at MoMA). Other posters have addressed the boundaries where the art system meets the real world: abortion rights, LGBT rights, racial discrimination under the Reagan-Bush administrations, domestic violence.

With #metoo, there’s a resurgent interest in their trailblazing. Though less prominent than the cases of Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen and other cultural heavy-hitters, the art world has been in the throes of its own controversies: influential curators finally losing their jobs after years of sexual harassment; magazine publishers caught out sending lurid, inappropriate texts to office juniors. Then there’s the case of Chuck Close, one of the most significant painters of the past 40 years, accused by several women in late 2017 and early 2018 of sexual misconduct.

The Guerrilla Girls, unsurprisingly, stepped up to the plate with a poster: “3 ways to write a museum label when the artist is a sexual predator”. And the example they used wasn’t just Chuck Close, the artist — but Chuck Close’s official portrait of fellow sexual miscreant Bill Clinton. The prototype labels they propose for the portrait are as hilarious as they are scathing. The first is “for museums afraid of alienating billionaire trustees and collectors who donated the work”; the second, “for museums conflicted about disclosing an artist’s abuse next to his art”; and the third, and most detailed, “for museums who need help from the Guerrilla Girls”.

That final level of “caped crusader” status is richly deserved, given the three decades the group has been fighting for equality and rights. “We’re in a new era of art and activism,” Kahlo says. “The makers of art — artists — and many of the people who love art have come to realise the consumers of art — collectors and museums — have rigged the game and made it about money and winner-take-all capitalism. We need to bring the art world back to a place where art is about ideas to be considered and debated and not just bought and sold for ever-higher prices.”

There is, though, a danger, with the creation of the Portfolio Compleat, of the Guerrilla Girls becoming complicit in the very system they’re trying to critique: the male-dominated institutions that still define who gets bought, what gets seen, and how we see it. But Kahlo doesn’t see this as a problem. “We began to realise back in the early 90s that our work has an artistic and historical value as well as activist value,” she explains. “Each work we’ve done has its own concept and qualities but all together they comprise a historical record of what was and is happening [in] the world. We think of the portfolio as a piece of art herstory that belongs in museums and libraries that will protect and preserve it. We imagine a time in the future when a viewer will come across our portfolio in a collection, next to a multimillion-dollar painting, and say, ‘Oh, all that was happening at the same time?’”

Every week in the contemporary art world, it seems like new stars are rising, and yet some things remain the same: the pace of change, when it comes to equal representation, feels glacial at times. We’re lucky that one of those things that doesn’t change, and doesn’t go away, is the conscience of a group of women wearing gorilla masks, keeping up the fight.

Reinventing the ‘F’ Word — Feminism! is showing at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki until October 13.

This piece originally appeared in the March-April 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Going Ape”.