Sep 26, 2019 Art

A Colin McCahon exhibition in Auckland builds towards the 1970s, when the artist was at his most visionary, writes Anthony Byrt.

In 2008, I flew from London to Zurich to see an exhibition by the New Zealand painter Judy Millar. When I got to the gallery, the paintings surprised me; rather than the exuberant colour of so much of her work, they were mostly pitched in greyscale — black-and-white, and a range in between.

They were partly inspired by her long, deep engagement with Colin McCahon’s work. We started to discuss McCahon’s greatest paintings — those white, biblical texts, in his characteristic brush-width cursive, painted on black grounds. I asked Millar what she thought had changed for McCahon when he was on the cusp of those works — and how he’d gone from being a gifted, regional artist to New Zealand’s most important and unique painter. Her answer was simple, but has stayed with me ever since: “He started,” she said, “to own the consequences of his thoughts.”

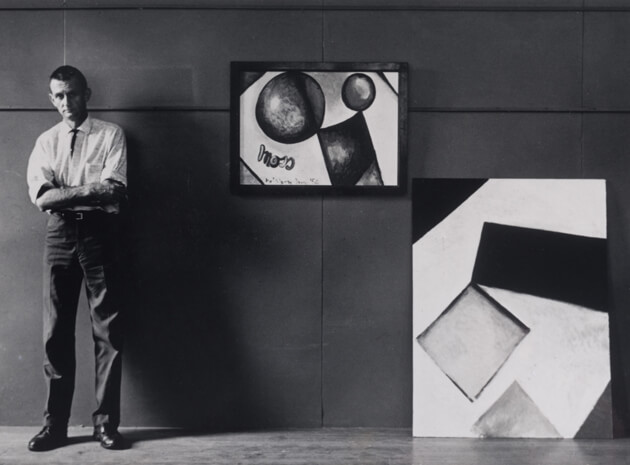

Whether the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki’s curators Ron Brownson and Julia Waite would frame McCahon’s dramatic shift in the same way, their superb, elegantly condensed exhibition A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland, maps exactly this transition.

This is the gallery’s way to mark the 100th anniversary of McCahon’s birth, a tribute not just to a great artist but also to a man who, for several years, worked at the institution. The exhibition’s curatorial premise is blissfully straightforward: a look at the three productive decades he spent painting in Auckland – the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s – which were conveniently demarcated by him working in three different locations: Titirangi’s French Bay (from 1953); Grey Lynn (from 1960); and Muriwai (from 1969). Three decades, three rooms, three different McCahons. But all of them building to the singular force of the late black-and-white works: the culmination, to paraphrase Millar, of that decision to be true to the visions inside his head.

The 1950s room displays the seeds of this change, from semi-Cubist portrayals of his west Auckland surrounds to works like Rocks at French Bay, 1959, a breathy, washy composition in ink and oil, on unstretched canvas (which would become a vital device for him). Towards the end of the room is 1961’s Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian, a geometric painting with the title painted at its base. It’s an essential work in the McCahon canon, but the wall-text also reveals it as an important step towards self-discovery. “Mondrian,” McCahon wrote, “came up in this century as a great barrier — the painting to END all painting. As a painter, how do you get around either a Michelangelo or a Mondrian? It seems that the only way is not more ‘masking-tape’ but more involvement in the human situation.”

McCahon’s decision to do exactly that — to involve himself more in the human situation — feels, in the exhibition, like his essential epiphany. And he did this precisely where he stood: here, in New Zealand, and even more specifically, in Auckland. The result was a remarkable, two-decade exploration of the complexity of the New Zealand experience: shaped by the collision between Maori and Pakeha, the power of our landscape, and the way faith might give us language to understand our place in the world. McCahon’s existential crisis — his desire to find his own way of being — was, ultimately, both outward- and forward-facing, an act of profound generosity to the culture around him.

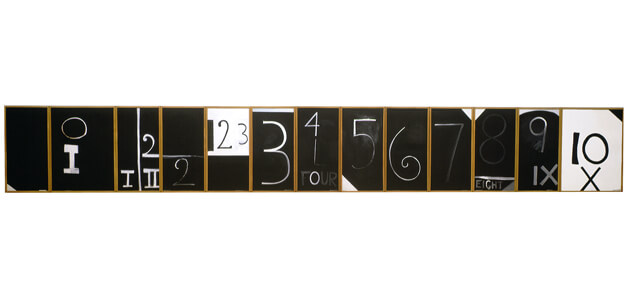

In the 1960s room, we see his new leaps of faith: 1965’s Numerals, a 13-panel journey through the dark, illuminated by Roman and Arabic numerals (a year later, he would make his monumental Fourteen Stations of the Cross). The first panel is a black void with a white triangle folding up from a lower corner; the second, an “I” below an “O” – numerals, of course, but also “Io”, framed by some historians as the Maori Supreme Being. The I is also the self under the O’s blinding white ring, like a solar eclipse. And on it goes, to “10” in the final panel, a one and zero with a giant “X” below, its colour scheme — black on white — reversing the composition of the first panel. Opposite this is the east window commissioned for Remuera’s Convent Chapel of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions in 1965-66, also in 13 parts, restored and shown to the public for the first time here — more obviously Catholic in its symbolism, but still shaped by the same sense of journey, both into and across a work of art.

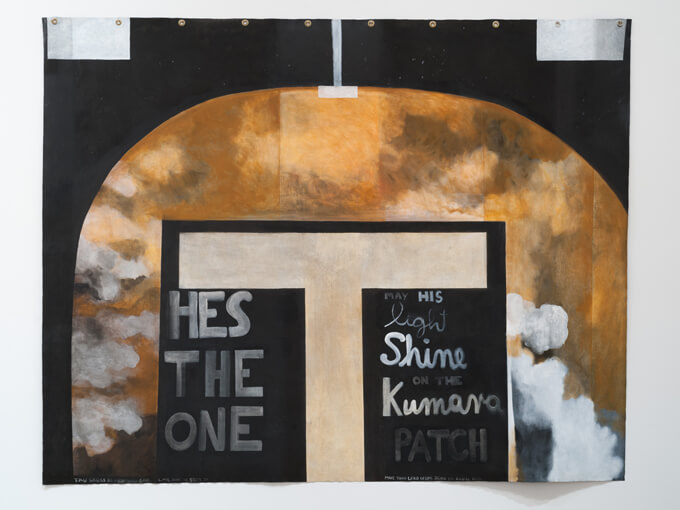

All of this, though, feels like the build-up to the exhibition’s final room: the 1970s, where McCahon becomes, with the help of whale sightings and the Muriwai cliffs, his most visionary self. There is 1973’s The Large Jump, in which Muriwai’s rock formations give inspiration to an enormous black block, with a broken diagonal line signalling the spiritual leap of the work’s title. There is May his Light Shine (Tau Cross), 1978-79, which simultaneously acknowledges the Calvary-like implications of Maunga- kiekie’s solitary tree and the maunga’s function as a site for Maori kumara patches (“May HIS light Shine on the Kumara PATCH”). There is the magnificent Are there not twelve hours of daylight, 1970, in which Christ’s words became pure white light on a black ground. And there is the massive Angels and bed no.4: Hi-fi, 1976-77, a black-and-white, angel’s-eye-view abstraction of a bedroom.

Most moving and powerful is the work that was possibly McCahon’s last: I considered all the acts of oppression, 1980-82, in which he quotes the Book of Ecclesiastes:

I considered all the acts of oppression here under the sun; I SAW the tears of the oppressed. Strength was on the side of their oppressors and there was no one to avenge them.

I counted the dead happy because they were dead, happier than the living who were still in life. More fortunate than either I reckoned man yet unborn, who had not witnessed the wicked deeds done here under the sun.

I considered all toil and all achievement and saw that it comes from rivalry between man and man. This too is emptiness and chasing the wind.

The text is divided into boxes but for a single, empty rectangle: a black void, deep and total. McCahon knew the void was devastation, but also potential: the generative space of being, particularly within a Maori framework. His “I SAW” is deliberately capitalised and seems to act as its own statement, McCahon slipping himself into the text. Quite what he saw about us, where we are, and how we live with each other, is difficult to know. But it was a clarity of vision that no one had before, or has had since. When it comes to New Zealand painting, McCahon is the light, and the dark: he is still everything.

A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, until 27 January 2020.

This piece originally appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “What he saw about us”.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to our weekly email